“You

know, there are two good things in life, freedom of thought and freedom of

action.” W. Somerset Maugham

“It’s the greatest mistake in the world to

think that one needs money to bring up a family. You need money to make them

gentlemen and ladies, but I don’t want my children to be ladies and gentlemen.”

W. Somerset Maugham, Of Human Bondage

“Criticism is purely destructive; anyone can

destroy, but not everyone can build up. … The important thing is to construct:

I am constructive; I am a poet.” W.

Somerset Maugham, Of Human Bondage

William Somerset Maugham was a

British playwright, novelist and short story writer. He was among the most

popular writers of his era and reputedly the highest paid author during the

1930s.

After losing both his parents

by the age of 10, Maugham was raised by a paternal uncle who was emotionally

cold. Not wanting to become a lawyer like other men in his family, Maugham

eventually trained and qualified as a medical doctor (physician). The first run

of his first novel, Liza of Lambeth (1897), sold out so rapidly that Maugham

gave up medicine to write full-time.

During the First World War, he

served with the Red Cross and in the ambulance corps, before being recruited in

1916 into the British Secret Intelligence Service, for which he worked in

Switzerland and Russia before the October Revolution of 1917. During and after

the war, he travelled in India and Southeast Asia; all of these experiences

were reflected in later short stories and novels.

Maugham returned to England

from his ambulance unit duties to promote Of Human Bondage. With that

completed, he was eager to assist the war effort again. As he was unable to

return to his ambulance unit, Syrie arranged for him to be introduced to a

high-ranking intelligence officer known as "R;" he was recruited by

John Wallinger.

In September 1915, Maugham

began work in Switzerland, as one of the network of British agents who operated

against the Berlin Committee, whose members included Virendranath Chattopadhyay,

an Indian revolutionary trying to use the war to create violence against the

British in his country. Maugham lived in Switzerland as a writer.

In 1916, Maugham travelled to

the Pacific to research his novel The Moon and Sixpence, based on the life of

Paul Gauguin. This was the first of his journeys through the late-Imperial

world of the 1920s and 1930s which inspired his novels. He became known as a

writer who portrayed the last days of colonialism in India, Southeast Asia,

China and the Pacific, although the books on which this reputation rests

represent only a fraction of his output.

On this and all subsequent

journeys, he was accompanied by Haxton, whom he regarded as indispensable to

his success as a writer. Maugham was painfully shy, and Haxton the extrovert

gathered human material which the author converted to fiction.

In June 1917, Maugham was asked

by Sir William Wiseman, an officer of the British Secret Intelligence Service

(later named MI6), to undertake a special mission in Russia.

It was part of an attempt to

keep the Provisional Government in power and Russia in the war by countering

German pacifist propaganda. Two and a half months later, the Bolsheviks took

control. Maugham subsequently said that if he had been able to get there six

months earlier, he might have succeeded. Quiet and observant, Maugham had a

good temperament for intelligence work; he believed he had inherited from his

lawyer father a gift for cool judgement and the ability to be undeceived by

facile appearances.

Maugham used his spying

experiences as the basis for Ashenden: Or the British Agent, a collection of

short stories about a gentlemanly, sophisticated, aloof spy. This character is

considered to have influenced Ian Fleming's later series of James Bond novels.

In 1922, Maugham dedicated his

book On A Chinese Screen to Syrie. This was a collection of 58 ultra-short

story sketches, which he had written during his 1920 travels through China and

Hong Kong, intending to expand the sketches later as a book.

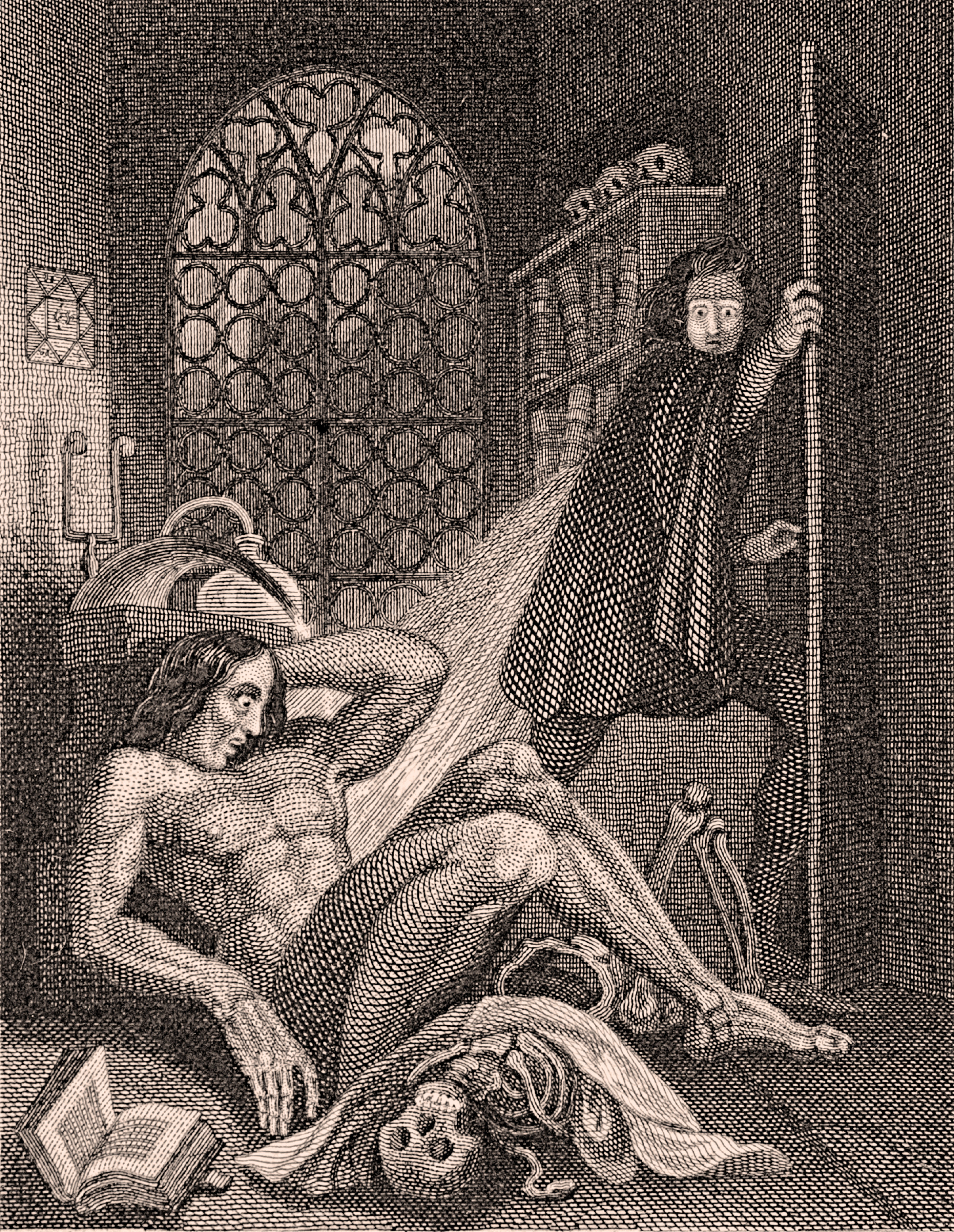

Dramatised from a story first

published in his collection The Casuarina Tree (1924), Maugham's play The

Letter, starring Gladys Cooper, had its premiere in London in 1927. Later, he

asked that Katharine Cornell play the lead in the 1927 Broadway version. The

play was adapted as a film by the same name in 1929, and again in 1940, for

which Bette Davis received an Oscar nomination. In 1951, Cornell was a great

success playing the lead in his comedy, The Constant Wife.

In 1926, Maugham bought the

Villa La Mauresque, on 9 acres at Cap Ferrat on the French

Riviera and it was his home for most of the rest of his life. There he hosted

one of the great literary and social salons of the 1920s and 30s. He continued

to be highly productive, writing plays, short stories, novels, essays and

travel books. By 1940, when the collapse of France and its occupation by the

German Third Reich forced Maugham to leave the French Riviera, he was a refugee

– but one of the wealthiest and most famous writers in the English-speaking

world.

Maugham's novel, An Appointment

in Samarra (1933), is based on an ancient Babylonian myth: Death is both the

narrator and a central character. The American writer John O'Hara credited

Maugham's novel as a creative inspiration for his own novel Appointment in

Samarra.[citation needed]

Maugham, by then in his

sixties, spent most of the Second World War in the United States, first in

Hollywood (he worked on many scripts, and was one of the first authors to make

significant money from film adaptations) and later in the South. While in the

US, he was asked by the British government to make patriotic speeches to induce

the US to aid Britain, if not necessarily become an allied combatant. After his

companion Gerald Haxton died in 1944, Maugham moved back to England. In 1946 he

returned to his villa in France, where he lived, interrupted by frequent and

long travels, until his death.

Maugham began a relationship

with Alan Searle, whom he had first met in 1928. A young man from the London

slum area of Bermondsey, Searle had already been kept by older men. He proved a

devoted if not a stimulating companion. One of Maugham's friends, describing

the difference between Haxton and Searle, said simply: "Gerald was

vintage, Alan was vin ordinaire."

Maugham's love life was almost

never smooth. He once confessed: "I have most loved people who cared

little or nothing for me and when people have loved me I have been embarrassed

... In order not to hurt their feelings, I have often acted a passion I did not

feel."

In 1962 Maugham sold a

collection of paintings, some of which had already been assigned to his

daughter Liza by deed. She sued her father and won a judgment of £230,000.

Maugham publicly disowned her and claimed she was not his biological daughter.

He adopted Searle as his son and heir but the adoption was annulled. In his

1962 volume of memoirs, Looking Back, he attacked the late Syrie Maugham and

wrote that Liza had been born before they married.

The memoir cost him several friends and

exposed him to much public ridicule. Liza and her husband Lord Glendevon

contested the change in Maugham's will in the French courts, and it was

overturned.

But, in 1965 Searle inherited

£50,000, the contents of the Villa La Mauresque, Maugham's manuscripts and his

revenue from copyrights for 30 years. Thereafter the copyrights passed to the

Royal Literary Fund.

There is no grave for Maugham.

His ashes were scattered near the Maugham Library, The King's School,

Canterbury. Liza Maugham, Lady Glendevon, died aged 83 in 1998, survived by her

four children (a son and a daughter by her first marriage to Vincent

Paravicini, and two more sons to Lord Glendevon). One of her grandchildren is

Derek Paravicini, who is a musical prodigy and autistic savant.

Commercial success with high

book sales, successful theatre productions and a string of film adaptations,

backed by astute stock market investments, allowed Maugham to live a very

comfortable life.

Small and weak as a boy,

Maugham had been proud even then of his stamina, and as an adult he kept

churning out the books, proud that he could. Yet, despite his triumphs, he

never attracted the highest respect from the critics or his peers. Maugham

attributed this to his lack of "lyrical quality", his small vocabulary,

and failure to make expert use of metaphor in his work. In 1934 the American

journalist and radio personality Alexander Woollcott offered Maugham some

language advice: "The female implies, and from that the male infers."

Maugham responded: "I am not yet too old to learn."

Maugham wrote at a time when

experimental modernist literature such as that of William Faulkner, Thomas

Mann, James Joyce and Virginia Woolf was gaining increasing popularity and

winning critical acclaim. In this context, his plain prose style was criticized

as "such a tissue of clichés that one's wonder is finally aroused at the

writer's ability to assemble so many and at his unfailing inability to put

anything in an individual way".

For a public man of Maugham's

generation, being openly gay was impossible. Whether his own orientation

disgusted him (as it did many at a time when homosexuality was widely

considered a moral failing as well as illegal) or whether he was trying to

disguise his leanings, Maugham wrote disparagingly of the gay artist. In Don

Fernando, a non-fiction book about his years living in Spain, Maugham pondered

a (perhaps fanciful) suggestion that the painter El Greco was homosexual:

"It cannot be denied that

the homosexual has a narrower outlook on the world than the normal man. In

certain respects the natural responses of the species are denied to him. Some

at least of the broad and typical human emotions he can never experience.

However subtly he sees life he cannot see it whole ... I cannot now help asking

myself whether what I see in El Greco's work of tortured fantasy and sinister

strangeness is not due to such a sexual abnormality as this."

But Maugham's homosexuality or

bisexuality is believed to have shaped his fiction in two ways. Since he tended

to see attractive women as sexual rivals, he often gave his women characters

sexual needs and appetites, in a way quite unusual for authors of his time.

Liza of Lambeth, Cakes and Ale,

Neil MacAdam and The Razor's Edge all featured women determined to feed their

strong sexual appetites, heedless of the result. As Maugham's sexual appetites

were then officially disapproved of, or criminal, in nearly all of the

countries in which he travelled, the author was unusually tolerant of the vices

of others.

Some readers and critics complained that

Maugham did not condemn what was bad in the villains of his fiction and plays.

Maugham replied: "It must be a fault in me that I am not gravely shocked

at the sins of others unless they personally affect me."

Maugham's public view of his

abilities remained modest. Toward the end of his career he described himself as

"in the very first row of the second-raters".In 1948 he wrote

"Great Novelists and Their Novels" in which he listed the ten best

novels of world literature in his view. In 1954, he was made a Companion of

Honour.

Maugham had begun collecting

theatrical paintings before the First World War; he continued to the point

where his collection was second only to that of the Garrick Club. In 1948 he

announced that he would bequeath this collection to the Trustees of the

National Theatre. From 1951, some 14 years before his death, his paintings

began their exhibition life. In 1994 they were placed on loan to the Theatre

Museum in Covent Garden.

PRACTICE RANDOM ACTS OF KINDNESS

Summer Morning

by Charles Simic

Summer Morning

I love to stay in bed

All morning,

Covers thrown off, naked,

Eyes closed, listening.

Outside they are opening

Their primers

In the little school

Of the corn field.

There's a smell of damp hay,

Of horses, laziness,

Summer sky and eternal life.

I know all the dark places

Where the sun hasn't reached yet,

Where the last cricket

Has just hushed; anthills

Where it sounds like it's raining;

Slumbering spiders spinning wedding dresses.

I pass over the farmhouses

Where the little mouths open to suck,

Barnyards where a man, naked to the waist,

Washes his face and shoulders with a hose,

Where the dishes begin to rattle in the kitchen.

The good tree with its voice

Of a mountain stream

Knows my steps.

It, too, hushes.

I stop and listen:

Somewhere close by

A stone cracks a knuckle,

Another rolls over in its sleep.

I hear a butterfly stirring

Inside a caterpillar,

I hear the dust talking

Of last night's storm.

Further ahead, someone

Even more silent

Passes over the grass

Without bending it.

And all of a sudden!

In the midst of that quiet,

It seems possible

To live simply on this earth.