There are several very good reasons to steal art. Stolen art has an enormous underground market, enough so that Interpol ranks art crime as the 4th highest-grossing criminal trade. Buyers run from crooked dealers, greedy collectors, forgers, and terrorist groups.

Secondly, art, which is essentially untraceable and relatively easy to conceal, can be used in place of cash when buying enormous quantities of drugs or arms. Museums will also pay millions to have stolen art returned and usually are willing to keep the law out of the theft unless there are cheated in the return deal.

In October of 1990, a group of New England mob knock-around guys fell back ass wards into the score of a lifetime when they pulled an art heist that gave them, a total in today’s value, of $500,000,000 in stolen works from a small Boston museum. The entire operation took less than an hour and a half to pull off. Two decades, later the paintings are still missing, and the robbery remains the largest art heist ever.

It happened at around midnight on Sunday morning, March 18, 1990, when a battered red Dodge Daytona pulled up near the side entrance of the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, a small but elite and privately-funded precious-art museum in downtown Boston. A century-old Italianate mansion was filled with uninsured art and was protected by an outdated security system.

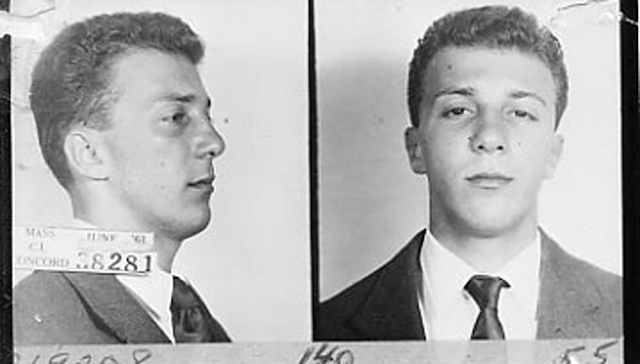

Richard Abath

At around 1 a.m., a security guard named Richard Abath returned to the front desk after patrolling the museum to switch positions with a fellow guard, the only other person in the building. The second guard on duty that night had recently earned a masters in performance from the New England Conservatory of Music and was working at the museum to earn a few extra dollars. He wasn’t scheduled to work that night but was called in when the regular night man called in sick.

What little that is known about the events just prior to the robbery is that two men with fake police uniforms waited for at least an hour in the battered red Dodge Daytona, trying to avoid being noticed by people leaving a Saint Patrick's Day party nearby. At 1:24 a.m., one of the two men walked up to the museum and pushed a buzzer near the door. When guard Abath answered, he was told by the man in a police uniform that they had a report of a disturbance in the museum courtyard and wanted to check it out.

Abath knew he was not allowed to let uninvited guests inside, but he was unsure on whether the rule applied to police officers. Several people who worked security at the museum when it was robbed told the cops that there were no rules against having personnel visitors come around at night after the museum closed, although Jon-Paul Kroger, head of security training at the time, was astounded that one of his guards would open the door to the museum after hours, even for police officers. As he explained to the FBI, the proper protocol was to take the officers names and badge numbers, call the police department and verify their identity, and only let them in if there were a legitimate reason.

By then, the second man had exited the car and was also standing

at the door waiting to be let in. Abath could see the men and their uniforms

and believed them to be police officers. With his partner on patrol and not

around to consult with, Abath decided to buzz in the men.

When the two fake cops arrived at the main security desk, one of

them told Abath that he looked familiar and that he was sure there was a

default warrant out for his arrest and demanded Abath step out from behind his

desk, where the only alarm button to alert police could be accessed. He was

asked for his ID, ordered to face the wall, and then handcuffed. Abath later

said believed the arrest was a misunderstanding until he realized he hadn't

been frisked before being cuffed, and one officer's mustache was made of wax. The

second security guard arrived minutes later and was also handcuffed, after

which he asked the intruders why he was being arrested. The thieves explained

that they were not being arrested, but rather this was a robbery, and proceeded

to take the guards to the museum's basement where they were handcuffed to

overhead pipes and had duct tape wrapped around their hands, feet, and heads.

Since the museum was equipped with motion detectors, the

thieves' movements throughout the museum were recorded and this is what the

cops learned; After tying up the guards, the thieves went upstairs to the Dutch

Room. As one of them approached Rembrandt's Self-Portrait (1629), a local alarm

sounded, which they immediately smashed. They then pulled the painting off the

wall and attempted to take the wooden panel out of its heavy frame.

Unsuccessful in the attempt, they left the painting on the floor. Due to the

manhandling ways the criminals conducted the robbery, cutting the paintings

from their frames and smashing frames for two Degas sketches, investigators

believe the thieves were amateur criminals, not experts commissioned to steal

particular works.

The detectors also showed that the thieves made two trips to

their car with the artwork during the theft, which lasted 81 minutes. Before

leaving, they visited the guards once more, telling them "You'll be

hearing from us in about a year," although they were never heard from

again. The guards remained handcuffed until police arrived at 8:15 a.m. later

that morning. At that, the thieves climbed into a red car and disappeared.

That was it. The greatest art heist in history was over.

Among the missing pieces were a Vermeer, a Manet, and five drawings by Degas. Two of the paintings — "Storm on the Sea of Galilee," Rembrandt's only known seascape, and Vermeer's "The Concert" which was Gardner's first major acquisition and one of only 34 known Vermeer works in the world.

A bronze finial was taken from the top of a Napoleonic flag, possibly appearing like gold to the thieves. The museum is offering a $100,000 reward for this piece alone. The thieves passed by two Raphael’s and a Botticelli painting. Titian's The Rape of Europa, which is one of the museum's most well-known and valuable pieces, was not stolen. The selection of works stolen puzzle’s the experts, specifically since more valuable artworks were available; why was that assortment of items was stolen despite the thieves being in the museum for enough time to take whatever they wished? The take from the robbery could have been double, even triple what it was but it became apparent that the thieves had no understanding of the art world and as result left behind more valuable pieces in the museum.

The thieves left behind virtually no clues at all. The view

clues that were left were sent to the FBI's Laboratory in Quantico, Virginia,

for retesting with the hope of finding new DNA evidence to identify the

culprits of the theft. However, in June of 2017, The Boston Globe reported that

some of the crime scene evidence collected by the FBI was missing. Even after

an exhaustive search, the FBI were unable to locate handcuffs and duct tape

used to immobilize the museum's two security guards that could have contained

traces of the thieves' DNA material.

The reason the evidence was sent to Quantico was because the

Federal Bureau of Investigation took control of the case on the grounds that

the artwork would likely cross state lines. The bureau believed then and now

that the heist was planned and carried out by the Patriarca mob and that for

the first few years after the heist, the paintings were shuffled between

Boston, Connecticut, Maine, and Pennsylvania by representatives of both the

Patriarchs and the Philadelphia mob.

At first, the FBI’s primary suspect was guard Richard Abath, a

rock musician moonlighting as a security guard. Abath was 23 years old and on

duty as a security guard the night that the museum was robbed. It was Abath who

opened the door for the two robbers. Also, a surveillance video shows a

security guard, whom the FBI believes is Abath, admitting an unidentified man

into the Museum the night before the infamous 1990 art heist. Abath remains a

suspect because, among other things, the motion detector equipment didn’t

register that there were intruders in the museum’s Blue Room, where a Manet

portrait was stolen from. It did register that the last person in the room was

Abath. His footsteps were registered on his initial patrol rounds before the

robbery began. However, he has, over almost three decades, cooperated fully with

investigators. Two Boston-area antique dealers, after seeing that same

surveillance video, said that they believe the second person with Abath is

someone in the antique trade but was known to be living in Florida who

"likes to brag about his relationship to a pair of notorious Boston art

thieves"

Off the record, the Bureau’s prime suspect has always been Robert A. Donati, AKA “Bobby D,” a lifelong hood and Made member of the New England Mob and part of Boston’s North End crew which was then, at the time of the robbery, under capo Vincent “Vinnie the Animal” Ferrara.

Ferrara took over the North End when the Angiulo brothers, New England mob underboss Jerry Angiulo and his four sibling lieutenants, were jailed in the 1980s.

Among Donati’s other criminal talents…which included murder for hire and flim-flam scams, he and his brother “Dickie D” Donati were accomplished second-story burglars. Shortly before the robbery, Donati was seen at a nightclub with a sack of police uniforms.

What probably led Donati to the Gardner heist was a story going

around in lower circles that the museum's security was ridiculously poor,

although the FBI is fairly certain Donati learned the story from a degenerate

gambler who once worked as a janitor at the Gardner and was into the mob for a

load of money. But the Donati’s were “Ham and eggers” low-level mob guys, a

step above, but not too far above, smash and grab artists. For them, the world

of extremely high-end art was far out of their realm of understanding, which

led law enforcement to conclude that there was a higher power behind the theft.

Brian McDevitt.

Also among the mountain of suspects was Brian McDevitt. The second guard has always insisted that it was a McDevitt who tied him up that night.

McDevitt’s fingerprints would be among the first to be sent to FBI headquarters in the wake of robbery. Raised in Swampscott, Massachusetts, McDevitt dropped out of Bates college after a year and became a crook, stealing $100,000 from a Boston lawyer’s safe deposit boxes. He used the money to finance a scam in Glens Falls, New York, where he masqueraded as a Vanderbilt and concocted an elaborate plan to empty The Hyde Collection of more than 70 masterpieces.

McDevitt was living in the Beacon Hill neighborhood when the

Gardner Museum was robbed. He was also seeing a young woman named Stéphanie

Rabinowitz. McDevitt told her that he was a staff writer for the television

show “The Wonder Years.” And three days before the Gardner robbery, he told

Rabinowitz he was going down to New York City for the Writers Guild Awards ceremony,

and that he’d be out of touch all weekend.

On March 18, 1990, the day the museum was robbed McDevitt begged Rabinowitz to be his alibi to explain his whereabouts when the museum was robbed but she refused. Two years later he told Rabinowitz, that he had been paid $300,000 to rob the Gardner Museum, and that he had left the country. McDevitt died at the age of 43 in Medellin, Colombia, in 2004.

Myles Connor

Another suspect was Myles Connor, Boston’s best art thief as well as an accomplished all around a professional burglar. Connor, the son of a decorated Policeman, robbed his first museum at age twenty when he was still a member of the 60’s rock group The Wild Ones.

His daring escape from a Maine jail and his daylight shoot-out with Boston police made him a walking legend in the New England underworld. According to Connor, the Donati’s came to him with their tip on the lax security at the Gardener and said they were interested in robbing the place. Connor claims that he and the Donati’s cased the museum in 1974 but decided to rob the Boston Museum of Fine Art across the street instead. They did, however, case the gardener again in 1989. But then Connor was locked up in January 1990 on a series of racketeering and art-theft charges and sentenced to serve 20 years in prison and the deal was off. Connor, who was known to have committed burglaries dressed as a police officer in the past, was also adept at using stolen art as a bargaining chip to secure immunity from prison and after being jailed in 1990, told the Fed’s he could get the Gardener art back in exchange for being released from prison as well as receive the cash reward, but the government turned him down. George Reissfelder had also been considered a suspect.

Reissfelder was a mob associate who had once served 16 years in the can for a crime he may not have committed. His lawyer in the retrial was John F. Kerry, later Senator John Kerry, who won by drumming up publicity for the case to use to promote his budding political career.

But once freed, Reissfelder, a died in the wool thug, returned to crime and drug addiction after his release. According to an informant named Robert Beauchamp, Reissfelder and another mob associate named David Turner visited him in Massachusetts state prison and told him they were planning a major robbery and asked how they might hide the valuables in the immediate aftermath. The Fed’s admit that Reissfelder did bare a remarkable resemblance to the sketch drawn of one of the thieves. Right after he died of a cocaine overdose in July 1991 Reissfelder’s brother told investigators later that he had seen what he thought to be Manet’s “Chez Tortoni,” one of the 13 artworks stolen from the Gardner, as having hung for a time over his brother’s bed.

Another version of the theft is that it was not a low-level job but rather that it was a mob operation through and through. That theory starts with David Houghton, an enforcer and street-tax collector and knew Bobby Donati for a mob hangout in Dorchester, TRC Auto Electric, a car repair shop owned by Patriarca hood Carmelo Merlino AKA The Auto Man.

Merlino had been convicted of robbing a Brinks armored truck in the late 1960s and opened the garage when he was paroled in the 1980s.

Brinks

Houghton was also a friend of Myles Connor who in turn introduced him to Bobby Donati. Connor claimed that Houghton was the other robber in the Gardener heist, but that very doubtful because Houghton, who weighed-in at well over 300 pounds, didn’t look anything like the men caught on the museum cameras. That took Houghton out of the picture.

So, in the end, almost all of the little evidence that was

available in the robbery pointed to Bobby Donati.

When Joe Russo, boss of the Boston mob, went to jail, “Cadillac

Frank” Salemme took over. Instead of balancing the badly shaken mob, Salemme

first order of business was to kill anyone who had been even remotely involved

in a botched assassination of him during the internal wars involving his

nemeses, the jailed Vincent Ferraro. One of the first Ferraro supporters he

intended to deal with Bobby Donati, who occasionally acted as a driver and

bodyguard for Ferraro. Donati’s badly beaten body (his throat was slit) was

found in the trunk of a car on September 24, 1991.

State Police figured the killer was an East Boston gangster named

Mark Rossetti, an FBI informant who would rise to the rank of Capo in the

organization. A year later, David Houghton, Donati’s probable partner in the

robbery, died of cancer (other have it as a heart attack) in 1991. That left

Carmelo Merlino AKA The Auto Man.

Tony Romano was a small-time criminal with drug problems. He had been paroled from the Massachusetts state prison after helping the FBI locate four priceless books, including a family Bible stolen from the John Quincy Adams family estate. Upon parole Romano either stumbled into a job at Carmello Merlino auto repair shop in Dorchester or was somehow planted there by the FBI.

It was from Romano, who was wearing a wire, that the feds learned that Merlino was plotting to rob a nearby armored car depot in Easton and that he had overheard Merlino talking about recovering the stolen Gardner Museum art. Over the entire year, Romano recorded dozens of conversations of Merlino planning out the armored car robbery.

The FBI moved in and arrested Merlino in 1994 for operating a

coke ring out of the garage. After the arrest, agents made it clear that all

charges could be dropped if Merlino led them to the stolen art, but the

gangster didn’t take the offer, meaning he either feared for his life if he

cooperated or, more likely, he was lying on the tapes about knowing the

location of the works. Instead, Merlino told the FBI that he was sure that a

hood named Richard Chicovsky AKA Fat Richie, could lead them to the stolen art.

The problem with that was that Chicovsky was a paid FBI informant who had

previously told the FBI that he assumed that Merlino could lead him to the

stolen artwork. Jailed for five years afterward, Merlino never came forward

with any more information and died in prison in 2005. As for Romano, the FBI’s

snitch, the Bureau relocated him to Florida, but his drug habit continued, and

he died shortly afterward of a brain aneurysm.

Another angle that the feds tracked down was the story that

supposedly Merlino had an overseas buyer for stolen high-end paintings through

a fence in Europe who would sell the goods to buyers in France as well as Irish

American representatives of the IRA, based in London, who would sell the art to

finance their war against Britain. Based on that, the Mob’s bosses had given Merlino

permission, specifically from East Boston mob chief and Patriarca street boss

and consigliere Joseph Russo, to rob a local art museum. So Merlino brought in

Houghton and Donati to pull off the job.

According to the FBI informants, Merlino’s supposed overseas buyer backed off when the Gardener robbery made international headlines for months and the FBI joined the case. Right after that, Merlino’s bosses in the mob, Vincent “Vinnie the Animal” Ferrara, and Joseph Russo, along with 19 others, were indicted on federal charges a week after the robbery. All of them were sent to jail eventually, in fact, Russo would die in prison, so the stolen art was the last thing anyone in the mob hierarchy cares about. So, Donati, Houghton, and Merlino stored the stolen artwork in Revere and went about the business of finding another buyer.

But despite what he may have said, Merlino had no actual experience in locating buyers for stolen multi-million dollar artwork but when Donati and Houghton died, the stolen art fell under Merlino’s control and he didn’t want it. Enter “The Three Bobby’s” “Bobby Boost” Guarente, the uncle to Bobby Donati’s suspected killer Mark Rossetti, “Boston Bobby” Luisi, Jr. and “Bobby the Cook” Gentile of Hartford. After an initial meeting with Merlino, police suspect that the Three Bobby’s made it their business to unload the painting to a buyer.

Merlino’s right-hand man was “Bobby Boost” Guarente, a

professional criminal and Mafia member with a rap sheet a mile long who served

jail time for leading a bank-robbery ring that took down at least 36 banks and/

or armored-trucks.

The Boost’s best friend and partner in crime was Bobby "The

Cook" Gentile (He says that his nickname, "The Cook", comes from

his passion for good food.) who was out of Hartford. On the books, he was

employed in the concrete-pouring business and, oddly enough, his company was

well known for their quality workmanship. Gentile's arrest record began during

the Eisenhower administration, although most of his involvement with the police

occurred in the 1960s. Convictions include aggravated assault, receipt of

stolen goods, illegal gun possession, larceny and gambling. He beat a

counterfeiting case.

He is handicapped by back pain, probably the result, according to multiple sources, of a blow his father delivered with a metal bar when he was 12 years old. He left school two years later to work for his father's masonry business and became the youngest bricklayer and cement mason to join the International Union of Brick Layers and Allied Craft Workers. Gentile and his brothers had a reputation as top concrete finishers, according to friends. When union construction slowed in the 1970s, he went to work for a builder of swimming pools in greater Hartford.

Gentile

He moved from swimming pools to used cars which is where he met Bobby Guarente, at one of the automobile auctions where dealers buy inventory. Gentile then took a stab at the restaurant business in the 1970s, but closed his place, the Italian Villa in Meriden, after two years. He also ran Clean County Used Cars and the cars lot, on Franklin Avenue in the Hartford's South End, was a local Hartford mob hangout. He put a stove and a refrigerator in a service bay and, as he wrote in a court filing, "cooked lunch for the boys. I like to cook," Gentile once said. "Macaroni’s. Chicken." The list of attendees at his luncheons in bay No. 1, according to someone familiar with the events, could read like a federal indictment. Among others: Hartford tough guy and mob soldier Anthony Volpe and John "Fast Jack" Farrell, the Patriarca family's card and dice man.

After Guarente got to know Gentile he introduced him to Robert

“Bobby” Luisi, the Boston mobster who would sponsor Gentile and Guarente for

membership in the Philadelphia mafia. Around 1997, Guarente and Gentile went to

work for Robert Luisi, Jr., AKA Boston Bobby, a capo in the Philadelphia mafia

operating in New England.

While in prison, Luisi, met some members of the Philly mob in prison who eventually inducted him into their family, something the Patriarca never offered. Under the infamous Philadelphia boss Skinny Joe Merlino,

Luisi was promoted to Capo and allowed to put together his own crew in New England. Luisi inducted his son, Bobby Guarente and Bobby Gentile into the mob on the same day in the same ceremony.

Guarente and Gentile mostly acted as bodyguards and cocaine

distributors for Luisi, whose father and brother were murdered in November 1995

in a Charlestown restaurant, two of the final victims of the Patriarca family

war. Guarente eventually became Luisi's second in command and Gentile became a

soldier in his crew.

The Crew didn’t last long. Luisi, Jr. was arrested on a

narcotics distribution conspiracy charge and almost immediately gave up

Guarente, Gentile and Boss Skinny Joey Merlino himself. In the end, everybody

went to jail. Luisi agreed to cooperate with the government.

Luisi was a major reason federal authorities believed the key to

recovering the stolen Gardner artwork lay with Bobby Guarente and Bobby

Gentile. According to Luisi, he told the FBI that Guarente had asked him at the

time if he knew how to fence stolen masterpieces as he had buried two of them

beneath the concrete slab of a house in Florida. Luisi said he didn’t, and

forgot about the conversation – that is until he was approached by the FBI upon

release from federal prison in 2012. Within weeks, the FBI was raiding

Gentile’s home outside of Hartford but did not find the art.

When Bobby Boost Guarente was released from prison in December

2000 and moved to a farmhouse was in north Portland, Maine, far in the woods.

He would die there from cancer in 2004. Six years later, in March of 2010,

Bobby Guarente’s widow told the FBI that she saw her husband hand Bobby The

Cook Gentile of Hartford two of the stolen Gardner paintings outside a

restaurant in Portland, Maine, sometime between 2002 and Guarente's death in

2004.

The feds believed the widow. The way the police heard the story

from other sources, was that Boston Bobby Luisi Jr. one of the three Bobby’s,

moved at least some of the art work out of New England where things were too

hot, down to Philadelphia while Bobby Boost Guarente moved some of the work

over to Hartford Connecticut into the waiting hands of Bobby the Cook Gentile.

Then, just before Bobby Boast Guarente went to prison, Bobby the Cook took the

art up to Bobby Boast’s place in Maine for safe keeping.

When the widow came forward , Bobby the Cook Gentile was

finishing a 30 month prison sentence after FBI agents raided Gentile’s

Manchester home and found handguns and ammunition and unregistered silencers,

none of which a convicted felon should have had in his possession. They also

charged him with selling illegally obtained prescription pain medication to a

law enforcement informant.

Gentile would later admit that he attended the Portland meeting

but denied taking the paintings. Gentile told the FBI that in March of 2002, he

drove from Boston to Portland, Maine to meet Guarente for dinner. He said he

went because Guarente was sick, broke and in need of a loan. "Bobby Guarente

always needed money," Gentile said. "One day he calls me. He said he

needed $300 for groceries. That's what he used to call it, 'Groceries.' He was

sick at the time." Gentile picked up the check for the dinner and

complained for years that Guarente's wife, Elene, ordered an expensive lobster

dinner. I'm a sucker," Gentile said. "I'm the one picking up the

check."

According to Guarente’s widow, Elene Marie, immediately after

finishing their meal at a Guarente passed at least two of the stolen paintings

to Bobby the Cook Gentile in the parking lot. Bobby the Cook Gentile is said to

have taken at least one piece, maybe more, and returned it to Connecticut.

Bobby Gentile said that Elene Marie was a liar and that she made the story up

to get back at him because after her husband died, Gentile, suffering from his

own maladies, was unable to continue sending her money. Gentile also told the

FBI that he has been victimized due to the competition for the $5 million

reward, which, he said, is all that Elene Marie is interested in. He said that

when she made the accusation she was, essentially, rolling the dice in hopes

that Bobby Gentile had the paintings and the FBI would find them in his

possession after her story gave the feds probable cause to conduct another

raid.

Investigators searched Guarente's farmhouse in Maine and found

nothing but the widow's session with the FBI in early 2010 brought life back

into the investigation and brought the otherwise low level and unknown Bobby

the Cook Gentile, into the center of it all.

A month after Guarente’s widow was interviewed, the FBI sent in

an undercover agent to Gentiles operation who recorded the gangster saying that

he had access to two of the stolen paintings that he would be willing to sell

them each for $500,000. To bury himself even further, Gentile was also recorded

boasting that he is a sworn mafia soldier in the Philadelphia family. Publicly,

and later in court, he denied knowing anything about the theft or the location

of the stolen art. An undercover FBI agent, posing as a marijuana seller, asked

Gentile why he was willing to sell the paintings rather collect the $5 million

reward. The agent told prosecutors "The answer, based on Mr. Gentile's own

words, was he felt that the feds were going to come after him anyway, even if

he was going to turn in the paintings for the $5 million reward"

After that, Sebastian "Sammy" Mozzicato, a Connecticut

mobster and his cousin were enlisted by the FBI to spy on Gentile. In return,

the bureau promised Mozzicato that if and when the paintings were recovered, he

could have the $5,000,000 in reward money. Among other things, Mozzicato told

the FBI that in the late 1990s, he was instructed to move a package of what he

suspects were paintings between cars outside a Waltham, Mass., condominium used

by him, Gentile, fellow mobster Bobby Guarente. A day or two later, Mozzicato

said Gentile and Guarente drove the purported art to Maine, where Guarente

owned a farmhouse.

Not long afterward, Mozzicato said he listened to an animated discussion

between Gentile and Guarente about whether they should give what they referred

to only as "a painting" to one of their Philadelphia mob bosses as

"tribute." Mozzicato said Gentile argued that the painting was

"worth a fortune" and told his old friend Guarente "You're out

of your (expletive) mind" to give it away. Also in the late 1990s,

Mozzicato said Gentile gave him photographs of five stolen paintings and asked

him to act as an intermediary in recruiting a buyer. Mozzicato said the potential

buyer was shocked by the paintings and complained, half-jokingly, that they

could be arrested just for talking about them. Mozzicato said Gentile then cut

him out of the deal but acknowledged later that the deal fell through.

Mozzicato said he and his cousin saw, on repeated occasions, what he believes

was the gilded eagle, cast two centuries ago in France as a finial for a

Napoleonic flagstaff. He said they saw it often on a shelf at Gem Auto, the

used car business Gentile formerly owned on Route 5 in South Windsor. Mozzicato

said he thinks Gentile later sold the eagle. Mozzicato said he identified the

finial from a photo provided by the FBI.

In the end, Gentile grew suspicious of Mozzicato and froze him

out. However, the feds now had enough solid information from Mozzicato to get a

third search warrant for Gentile’s property. During search agents found

explosives, a bullet-proof vest, Tasers, police scanners, a police scanner code

book, blackjacks, switch-blade knives, two dozen blank social security cards, a

South Carolina driver’s license issued under the alias Robert Gino, five

silencers, hundreds of rounds of ammunition, a California police badge, three

sets of handcuffs with the serial numbers ground off, police hats and what a

federal magistrate characterized as an "arsenal" of firearms. The

agents also noted that there was a surveillance camera trained on the approach

to his home. Hanging from a hook inside the front door was a loaded, 12-gauge

Mossberg shotgun with a pistol grip. Further inside the house, they found two

snub nose, .38-caliber revolvers and a .22-caliber derringer. In the 2012 raid,

a large cache of prescription painkillers that he had no prescription for, a

hand-written list of each of the stolen pieces of Isabella Gardner artwork accompanied

with their estimated black-market values and a copy of the March 19, 1990,

Boston Herald, which included major coverage of the Gardner heist.

Gentile has gave a simple explanations for the presence in his

home of a dozen weapons and related paraphernalia. He said some of it had been

there so long he forgot about it. He added that other material probably was

dropped off by a friend who is a "dump picker."

Gentile's lawyer added the laughable excuse that Gentile is a

hoarder. But neither the lawyer nor Gentile had an explanation for the list and

estimated value of the stolen paintings. However, an infamous art thief from

Massachusetts said that he wrote the list and that Gentile probably acquired

it, in a transaction not directly related to the robbery that may have been

nothing more than an attempted swindle.

In 2015, Gentile submitted to a lie detector test, denying

advanced knowledge of the heist or ever possessing any paintings. The result

showed a 0.1% chance that he was truthful. Gentile also reportedly failed an

FBI-administered lie-detector test regarding his knowledge of the whereabouts

of the art work

In 2018, Gentile, at age 81, was sentenced to 54 months in

prison on federal gun charges. Right afterward, dozens of FBI agents swarmed

over Gentile's front and back yards and found an empty hole in the back yard

someone had dug and then tried to cover up by placing a storage shed over it,

but it proved to be nothing but another dead end lead. A 2018 excavation of a

lot in Orlando, Florida, that Guarente had frequented also failed to uncover

any trace of the stolen works.

There is the possibility that neither Bobby Gentile or Bobby

Guarente didn’t steal the art work, nor did they know where it was but that

they had every intention of collecting the $5 million reward that the museum

was offering for the recovery in the late 1990s. Both men were reported to be

obsessed with the reward money.

Bobby Guarente

The museum initially offered a reward of $5 million for

information leading to the art's recovery, but in 2017 this was temporarily

doubled to $10 million, with an expiration date set to the end of the year.

That was extended into 2018 following helpful tips from the public. No one has

taken them up on the offer.

Almost three decades later, the theory is, rumor actually, that

the paintings are in Ireland, having fallen into the hands of the IRA which

hoped to use the art work to finance pensions for their members who fought in

the guerrilla wars against the British in the 1960s and 1970s.

One way or the other, the case is cold now. Although the FBI reports, vaguely, that several sightings of the missing art had been recently authenticated, the hundreds of clues that started it off are done, all of them having been proven useless. The statute of limitations in the case have expired long ago. No single motive or pattern has emerged through the thousands of pages of evidence gathered.