AS WE TOPPED THE LOW, pine-clad

ridge and A looked into the hot, dry valley, Wolf Voice, my Cheyenne

interpreter, pointed at a little log cabin, toward the green line of alders

wherein the Rosebud ran, and said: "His house -- Two Moon."

As we drew near we came to a

puzzling fork in the road. The left branch skirted a corner of a wire fence,

the right turned into a field. We started to the left, but the waving of a

blanket in the hands of a man at the cabin door directed us to the right. As we

drew nearer we perceived Two Moon spreading blankets in the scant shade of his

low cabin. Some young Cheyennes were grinding a sickle. A couple of children

were playing about the little log stables. The barn-yard and buildings were

like those of a white settler on the new and arid sod. It was all barren and

unlovely -- the home of poverty.

As we dismounted at the door Two

Moon came out to meet us with hand outstretched. "How" he said, with

the heartiest, long-drawn note of welcome. He motioned us to be seated on the

blankets which he had spread for us upon seeing our approach. Nothing could exceed

the dignity and sincerity of his greeting.

As we took seats he brought out

tobacco and a pipe. He was a tall old man, of a fine, clear brown complexion,

big-chested, erect, and martial of bearing. His smiling face was broadly

benignant, and his manners were courteous and manly.

While he cut his tobacco Wolf

Voice interpreted my wishes to him. I said, "Two Moon, I have come to hear

your story of the Custer battle, for they tell me you were a chief there. After

you tell me the story, I want to take some photographs of you. I want you to

signal with a blanket as the great chiefs used to do in fight."

Wolf Voice made this known to

him, delivering also a message from the agents, and at every pause Two Moon

uttered deep-voiced notes of comprehension. "Ai," "A-ah,"

"Hoh,"-these sounds are commonly called "grunts," but they

were low, long-drawn expulsions of breath, very expressive.

Then a long silence intervened.

The old man mused. It required time to go from the silence of the hot valley,

the shadow of his little cabin, and the wire fence of his pasture, back to the

days of his youth. When he began to speak, it was with great deliberation. His

face became each moment graver and his eyes more introspective.

"Two Moon does not like to

talk about the days of fighting but since you are to make a book, and the agent

says you are a friend to Grinnell (George B. Grinnell, whom the Cheyennes,

Blackfeet, and Gros Ventres love and honor), I will tell you about it-the

truth. It is now a long time ago, and my words do not come quickly.

"That spring [1876] I was

camped on Powder River with fifty lodges of my people -- Cheyennes. The place

is near what is now Fort McKinney. One morning soldiers charged my camp. They

were in command of Three Fingers [Colonel McKenzie]. We were surprised and

scattered, leaving our ponies. The soldiers ran all our horses off. That night

the soldiers slept, leaving the horses one side; so we crept up and stole them

back again, and then we went away.

"We traveled far, and one

day we met a big camp of Sioux at Charcoal Butte. We camped with the Sioux, and

had a good time, plenty grass, plenty game, good water. Crazy Horse was head

chief of the camp. Sitting Bull was camped a little ways below, on the Little

Missouri River.

"Crazy Horse said to me,

`I'm glad you are come. We are going to fight the white man again.'

"The camp was already full

of wounded men, women, and children.

"I said to Crazy Horse, `All

right. I am ready to fight. I have fought already. My people have been killed,

my horses stolen; I am satisfied to fight'.

Here the old man paused a moment,

and his face took on a lofty and somber expression.

"I believed at that time the

Great Spirits had made Sioux, put them there," he drew a circle to the

right "and white men and Cheyennes here," -- indicating two places to

the left -- `expecting them to fight. The Great Spirits I thought liked to see

the fight; it was to them all the same like playing. So I thought then about

fighting." As he said this, he made me feel for one moment the power of a

sardonic god whose drama was the wars of men.

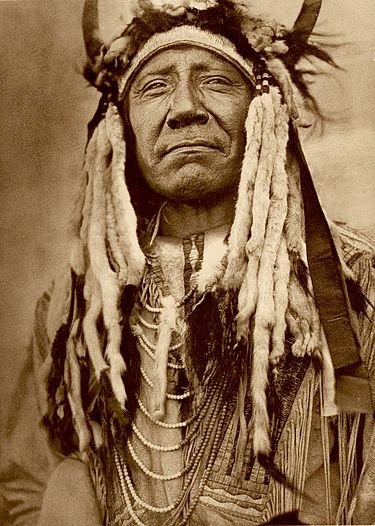

Northern Cheyenne War Chief Two

Moon in 1879, three years after the Battle of the Little Big Horn"About

May, when the grass was tall and the horses strong, we broke camp and started

across the country to the mouth of the Tongue River. Then Sitting Bull and

Crazy Horse and all went up the Rosebud. There we had a big fight with General

Crook, and whipped him. Many soldiers were killed -- few Indians. It was a

great fight, much smoke and dust.

"From there we all went over

the divide, and camped in the valley of Little Horn. Everybody thought, `Now we

are out of the white man's country. He can live there, we will live here.'

After a few days, one morning when I was in camp north of Sitting Bull, a Sioux

messenger rode up and said, `Let everybody paint up, cook, and get ready for a

big dance.'

"Cheyennes then went to work

to cook, cut up tobacco, and get ready. We all thought to dance all day. We

were very glad to think we were far away from the white man.

"I went to water my horses

at the creek, and washed them off with cool water, then took a swim myself. I

came back to the camp afoot. When I got near my lodge, I looked up the Little

Horn towards Sitting Bull's camp. I saw a great dust rising. It looked like a

whirlwind. Soon Sioux horseman came rushing into camp shouting: 'Soldiers come!

Plenty white soldiers.'

"I ran into my lodge, and

said to my brotherin-law, 'Get your horses; the white man is coming. Everybody

run for horses.'

"Outside, far up the valley,

I heard a battle cry, Hay-ay, hay-ay! I heard shooting, too, this way [clapping

his hands very fast]. I couldn't see any Indians. Everybody was getting horses

and saddles. After I had caught my horse, a Sioux warrior came again and said,

'Many soldiers are coming.'

"Then he said to the women,

'Get out of the way, we are going to have hard fight.'

"I said, `All right, I am

ready.'

"I got on my horse, and rode

out into my camp. I called out to the people all running about: `I am Two Moon,

your chief. Don't run away. Stay here and fight. You must stay and fight the

white soldiers. I shall stay even if I am to be killed.

"I rode swiftly toward

Sitting Bull's camp. There I saw the white soldiers fighting in a line [Reno's

men]. Indians covered the flat. They began to drive the soldiers all mixed up

-- Sioux, then soldiers, then more Sioux, and all shooting. The air was full of

smoke and dust. I saw the soldiers fall back and drop into the riverbed like

buffalo fleeing. They had no time to look for a crossing. The Sioux chased them

up the hill, where they met more soldiers in wagons, and then messengers came

saying more soldiers were going to kill the women, and the Sioux turned back.

Chief Gall was there fighting. Crazy Horse also.

"I then rode toward my camp,

and stopped squaws from carrying off lodges. While I was sitting on my horse I

saw flags come up over the hill to the east like that [he raised his

finger-tips]. Then the soldiers rose all at once, all on horses, like this [he

put his fingers behind each other to indicate that Custer appeared marching in

columns of fours]. They formed into three branches [squadrons] with a little

ways between. Then a bugle sounded, and they all got off horses, and some

soldiers led the horses back over the hill.

"Then the Sioux rode up the

ridge on all sides, riding very fast. The Cheyennes went up the left way. Then

the shooting was quick, quick. Pop-pop-pop very fast. Some of the soldiers were

down on their knees, some standing. Officers all in front. The smoke was like a

great cloud, and everywhere the Sioux went the dust rose like smoke. We circled

all round them -- swirling like water round a stone. We shoot, we ride fast, we

shoot again. Soldiers drop, and horses fall on them. Soldiers in line drop, but

one man rides up and down the line -- all the time shouting. He rode a sorrel

horse with white face and white fore-legs. I don't know who he was. He was a

brave man.

"Indians keep swirling round

and round, and the soldiers killed only a few. Many soldiers fell. At last all

horses killed but five. Once in a while some man would break out and run toward

the river, but he would fall. At last about a hundred men and five horsemen

stood on the hill all bunched together. All along the bugler kept blowing his

commands. He was very brave too. Then a chief was killed. I hear it was Long

Hair [Custer], I don't know; and then the five horsemen and the bunch of men,

may be so forty, started toward the river. The man on the sorrel horse led

them, shouting all the time. He wore buckskin shirt, and had long black hair and

mustache. He fought hard with a big knife. His men were all covered with white

dust.

I couldn't tell whether they were officers or not. One man all alone ran

far down toward the river, then round up over the hill. I thought he was going

to escape, but a Sioux fired and hit him in the head. He was the last man. He

wore braid on his arms. [Note: others said this was a suicide and the American

shot himself in the head after he had made his getaway.]

"All the soldiers were now

killed, and the bodies were stripped. After that no one could tell which were

officers. The bodies were left where they fell. We had no dance that night. We

were sorrowful.

"Next day four Sioux chiefs

and two Cheyennes and I, Two Moon, went upon the battlefield to count the dead.

One man carried a little bundle of sticks. When we came to dead men, we took a

little stick and gave it to another man, so we counted the dead. There were

388. There were thirty-nine Sioux and seven Cheyennes killed, and about a

hundred wounded.

"Some white soldiers were cut

with knives, to makes sure they were dead; and the war women had mangled some.

Most of them were left just where they fell. We came to the man with big

mustache; he lay down the hill towards the river. (Custer fell up higher on the

ridge.) The Indians did not take his buckskin shirt. The Sioux said, `That is a

big chief. That is Long Hair.' I don't know. I had never seen him. The man on

the white-faced horse was the bravest man.

"That day as the sun was

getting low our young men came up the Little Horn riding hard. Many white

soldiers were coming in a big boat, and when we looked we could see the smoke

rising. I called my people together, and we hurried up the Little Horn, into

Rotton Grass Valley. We camped there three days, and then rode swiftly back over

our old trail to the east. Sitting Bull went back into the Rosebud and down the

Yellowstone, and away to the north. I did not see him again."

The old man paused and filled his pipe. His story was done. His mind came

back to his poor people on the barren land where the rain seldom falls.

"That was a long time ago. I

am now old, and my mind has changed. I would rather see my people living in

houses and singing and dancing. You have talked with me about fighting, and I

have told you of the time long ago. All that is past. I think of these things

now: First, that our reservation shall be fenced and the white settlers kept

out and our young men kept in. Then there will be no trouble. Second, I want to

see my people raising cattle and making butter. Last, I want to see my people

going to school to learn the white man's way. That is all."

There was something placid and

powerful in the lines of the chief's broad brow, and his gestures were dramatic

and noble in sweep. His extended arms, his musing eyes, his deep voice combined

to express a meditative solemnity profoundly impressive. There was no anger in

his voice, and no reminiscent ferocity. All that was strong and fine and

distinctive in the Cheyenne character came out in the old man's talk. He seemed

the leader and the thoughtful man he really is -- patient under injustice,

courteous even to his enemies.

Two Moon's Story of the Battle, A

Cheyenne's account of the Battle of the Little Bighorn. From McClure's

Magazine, September, 1898.

Two Moons (1847–1917), was one of

the Cheyenne chiefs who took part in the Battle of the Little Bighorn and other

battles against the United States Army. (Including the Battle of the Rosebud

against General Crook on June 17, 1876, in the Montana Territory)

He the surrendered of his

Cheyenne band to Miles at Fort Keogh in April 1877 and enlisted as an Indian

Scout under General Miles. Amiable, humorous and with no animosity to whites, General Miles appointed him head Chief of the

Cheyenne Northern Reservation. As head Chief, Two Moons played a crucial role

in the surrender of Chief Little Cow's Cheyenne band at Fort Keogh.

Two Moons traveled on multiple

occasions to Washington, D.C., to discuss and fight for the future of the

Northern Cheyenne people and to better the conditions that existed on the

reservation. In 1914, Two Moons met with President Woodrow Wilson to discuss

these matters. He was also one of the models selected for James Fraser's famous

Buffalo Nickel. Two Moons died in 1917 at his home in Montana at the age of 70.