The World is a Beautiful Place – Lawrence Ferlinghetti

"The world is a beautiful place"

The world is a beautiful place

to be born into

if you don’t mind happiness

not always being

so very much fun

if you don’t mind a touch of hell

now and then

just when everything is fine

because even in heaven

they don’t sing

all the time

The world is a beautiful place

to be born into

if you don’t mind some people dying

all the time

or maybe only starving

some of the time

which isn’t half so bad

if it isn’t you

Oh the world is a beautiful place

to be born into

if you don’t much mind

a few dead minds

in the higher places

or a bomb or two

now and then

in your upturned faces

or such other improprieties

as our Name Brand society

is prey to

with its men of distinction

and its men of extinction

and its priests

and other patrolmen

and its various segregations

and congressional investigations

and other constipations

that our fool flesh

is heir to

Yes the world is the best place of all

for a lot of such things as

making the fun scene

and making the love scene

and making the sad scene

and singing low songs of having

inspirations

and walking around

looking at everything

and smelling flowers

and goosing statues

and even thinking

and kissing people and

making babies and wearing pants

and waving hats and

dancing

and going swimming in rivers

on picnics

in the middle of the summer

and just generally

‘living it up’

Yes

but then right in the middle of it

comes the smiling

mortician

Marjorie Rawlings

Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings (August

8, 1896 – December 14, 1953) was an author who lived in rural Florida and wrote

novels with rural themes and settings.

Her best known work, The Yearling, about a boy

who adopts an orphaned fawn, won a Pulitzer Prize for fiction in 1939 and was

later made into a movie of the same name. The book was written long before the

concept of young adult fiction but is now commonly included in teen-reading

lists.

In 1928, with a small inheritance

from her mother, the Rawlingses purchased a 72-acre orange grove near

Hawthorne, Florida, in a hamlet named Cross Creek for its location between

Orange Lake and Lochloosa Lake.

She was fascinated with the

remote wilderness and the lives of Cross Creek residents, her "Florida

cracker" neighbors, and felt a profound and transforming connection to the

region and the land.

Wary at first, the local

residents soon warmed to her and opened up their lives and experiences to her.

Marjorie actually made many visits to meet with Calvin and Mary Long to observe

their family relationships. This relationship ended up being used as a model

for the family in her most successful novel, The Yearling. The Longs lived in a

clearing named Pat's Island, but Marjorie renamed the clearing "Baxter's

Island." Marjorie filled several notebooks with descriptions of the

animals, plants, Southern dialect, and recipes and used these descriptions in

her writings.

Her first novel, South Moon

Under, was published in 1933. The book captured the richness of Cross Creek and

its environs in telling the story of a young man, Lant, who must support

himself and his mother by making and selling moonshine, and what he must do

when a traitorous cousin threatens to turn him in. Moonshiners were the subject

of several of her stories, and Rawlings lived with a moonshiner for several

weeks near Ocala to prepare for writing the book. South Moon Under was included

in the Book-of-the-Month Club and was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize.

She found immense success in 1938

with The Yearling, a story about a Florida boy and his pet deer and his

relationship with his father, which she originally intended as a story for

young readers. It was selected for the Book-of-the-Month Club, and it won the

Pulitzer Prize for Fiction in 1939. MGM purchased the rights to the film

version, which was released in 1946, and it made her famous. In 1942, Rawlings

published Cross Creek, an autobiographical account of her relationships with

her neighbors and her beloved Florida hammocks. Again it was chosen by the

Book-of-the-Month Club, and it was even released in a special armed forces

edition, sent to servicemen during World War II.

Rawlings' final novel, The

Sojourner, published in 1953 and set in a northern setting, was about the life

of a man and his relationship to his family: a difficult mother who favors her

other, first-born son and his relationship to this absent older brother. To

absorb the natural setting so vital to her writing, she bought an old farmhouse

in Van Hornesville, New York and spent part of each year there until her death.

The novel was less well-received

critically than her Florida writings and did little to enhance her literary

reputation. She published 33 short stories from 1912–49. As many of Rawling's

works were centered in the North and Central Florida area, she was often

considered a regional writer. Rawlings herself rejected this label saying,

"I don't hold any brief for regionalism, and I don't hold with the

regional novel as such … don't make a novel about them unless they have a

larger meaning than just quaintness."

In her memoir Cross Creek first

published in 1942, Rawlings described how she owned 72 acres of land and also

hired a number of people over the years to help her with day-to-day chores and

activities. An entire chapter of the book is dedicated to one woman she hired,

whose name was Beatrice, but who was affectionately known as

"GeeChee", because the woman was ethnically part of the GeeChee

people. In the book Rawlings said GeeChee's mother lived in nearby Hawthorne,

Florida and that GeeChee was blind in one eye from a fight in which she had

been involved. GeeChee was employed by Rawlings on and off for nearly two years

in which GeeChee dutifully made life easier for Rawlings. GeeChee revealed to

Rawlings that her boyfriend named Leroy was serving time in prison for

manslaughter, and asked Rawlings for help in gaining his release. She arranged

for Leroy to be paroled to her and come work for her farm and had a wedding on

the grounds for Beatrice and Leroy. After a few weeks, Leroy aggressively

demanded more earnings from Rawlings and threatened her. She decided he had to

leave, which caused her distress because she did not want GeeChee to go with

him, which she was sure she would. GeeChee eventually decided to stay with

Rawlings, but then began to drink heavily and abandoned her. Weeks later,

Rawlings searched for GeeChee, found her, and drove her back to the farm,

describing GeeChee as a "Black Florence Nightingale". GeeChee was

unable to stop herself from drinking, which led a heartbroken Rawlings to

dismiss her. Rawlings stated in her autobiography "No maid of perfection —

and now I have one — can fill the strange emptiness she left in a remote corner

of my heart. I think of her often, and I know she does of me, for she comes

once a year to see me".

When Cross Creek was turned into

a 1983 film, actress Alfre Woodard was nominated for the Academy Award for Best

Supporting Actress for her performance as GeeChee.

In 1943, Rawlings faced a libel

suit for Cross Creek, filed by her neighbor Zelma Cason, whom Rawlings had met

the first day she moved to Florida. Cason had helped to soothe the mother made

upset by her son's depiction in "Jacob's Ladder".

Cason claimed Rawlings made her

out to be a "hussy". Rawlings had assumed their friendship was intact

and spoke with her immediately. Cason went ahead with the lawsuit seeking

$100,000 US for invasion of privacy (as the courts found libel too ambiguous).

It was a cause of action that had never been argued in a Florida court.

Rawlings used Cason's forename in

the book, but described her in this passage:

Zelma is an ageless spinster

resembling an angry and efficient canary. She manages her orange grove and as

much of the village and county as needs management or will submit to it. I

cannot decide whether she should have been a man or a mother. She combines the

more violent characteristics of both and those who ask for or accept her

ministrations think nothing at being cursed loudly at the very instant of being

tenderly fed, clothed, nursed, or guided through their troubles.

Cason was represented by one of

the first female lawyers in Florida, Kate Walton. Cason was reportedly profane

indeed (one of her neighbors reported her swearing could be heard for a quarter

of a mile), wore pants, had a fascination with guns, and was just as extraordinarily

independent as Rawlings herself.

Rawlings won the case and enjoyed

a brief vindication, but the verdict was overturned in appellate court and

Rawlings was ordered to pay damages in the amount of $1. The toll the case took

on Rawlings was great, in both time and emotion. Reportedly, Rawlings had been

shocked to learn of Cason's reaction to the book and felt betrayed. After the

case was over, she spent less time in Cross Creek and never wrote another book

about Florida, though she had been considering doing a sequel to Cross Creek.

The books illustrations were done

by Newell Convers Wyeth (October 22, 1882 – October 19, 1945), known as N. C.

Wyeth. During his lifetime, Wyeth created more than 3,000 paintings and

illustrated 112 books, 25 of them for Scribner's, the Scribner Classics, which

is the work for which he is best known. Wyeth was a realist painter at a time when the

camera and photography began to compete with his craft. Sometimes seen as

melodramatic, his illustrations were designed to be understood quickly. Wyeth,

who was both a painter and an illustrator, understood the difference, and said

in 1908, "Painting and illustration cannot be mixed—one cannot merge from

one into the other." In October 1945, Wyeth and his grandson (Nathaniel C.

Wyeth's son) were killed when the automobile they were riding in was struck by

a freight train at a railway crossing

near his Chadds Ford home

Government Troops Firing on Demonstrators, Corner of Nevsky Prospect and Sadovaya Street, St. Petersburg, Russia] by Karl Karlovich Bulla

Bloody

Sunday Massacre in Russia

Well on its way to losing a war

against Japan in the Far East, czarist Russia is wracked with internal

discontent that finally explodes into violence in St. Petersburg in what will

become known as the Bloody Sunday Massacre.

Under the weak-willed Romanov

Czar Nicholas II, who ascended to the throne in 1894, Russia had become more

corrupt and oppressive than ever before. Plagued by the fear that his line

would not continue—his only son, Alexis, suffered from hemophilia—Nicholas fell

under the influence of such unsavory characters as Grigory Rasputin, the

so-called mad monk. Russia’s imperialist interests in Manchuria at the turn of

the century brought on the Russo-Japanese War, which began in February 1904.

Meanwhile, revolutionary leaders, most notably the exiled Vladimir Lenin, were

gathering forces of socialist rebellion aimed at toppling the czar.

To drum up support for the

unpopular war against Japan, the Russian government allowed a conference of the

zemstvos, or the regional governments instituted by Nicholas’s grandfather

Alexander II, in St. Petersburg in November 1904. The demands for reform made

at this congress went unmet and more radical socialist and workers’ groups

decided to take a different tack.

On January 22, 1905, a group of

workers led by the radical priest Georgy Apollonovich Gapon marched to the

czar’s Winter Palace in St. Petersburg to make their demands. Imperial forces

opened fire on the demonstrators, killing and wounding hundreds. Strikes and

riots broke out throughout the country in outraged response to the massacre, to

which Nicholas responded by promising the formation of a series of

representative assemblies, or Dumas, to work toward reform.

Internal tension in Russia

continued to build over the next decade, however, as the regime proved

unwilling to truly change its repressive ways and radical socialist groups,

including Lenin’s Bolsheviks, became stronger, drawing ever closer to their

revolutionary goals. The situation would finally come to a head more than 10

years later as Russia’s resources were stretched to the breaking point by the

demands of World War I.

Edvard Grieg – Peer Gynt Suite No. 1, Op. 46: In the Hall of the Mountain King

Grieg's music drew on the

Norwegian folk tunes of his homeland. ... Grieg's 'Peer Gynt Suite' tells the story

of a young boy – Peer Gynt, who falls in love with a girl but is not allowed to

marry her. He runs away into the mountains but is captured by trolls who take

him to their King.

Destruction—Joanne Kyger

First of all do you remember the

way a bear goes through

a cabin when nobody is home? He

goes through

the front door. I mean he really

goes through it. Then

he takes the cupboard off the

wall and eats a can of lard.

He eats all the apples, limes,

dates, bottled decaffeinated

coffee, and 35 pounds of granola.

The asparagus soup cans

fall to the floor. Yum! He chomps

up Norwegian crackers

stashed for the winter. And the

bouillon, salt, pepper,

paprika, garlic, onions,

potatoes.

He rips the Green Tara

poster from the wall. Tries the

Coleman Mustard. Spills

the ink, tracks in the flour.

Goes up stairs and takes

a shit. Rips open the water bed,

eats the incense and

drinks the perfume. Knocks over

the Japanese tansu

and the Persian miniature of a

man on horseback watching

a woman bathing.

Knocks Shelter, Whole Earth

Catalogue,

Planet Drum, Northern Mists,

Truck Tracks, and

Women's Sports into the oozing

water bed mess.

He goes down stairs and out the

back wall. He keeps on going

for a long way and finds a good

cave to sleep it all off.

Luckily he ate the whole medicine

cabinet, including stash

of LSD, Peyote, Psilocybin,

Amanita, Benzedrine, Valium

and aspirin.

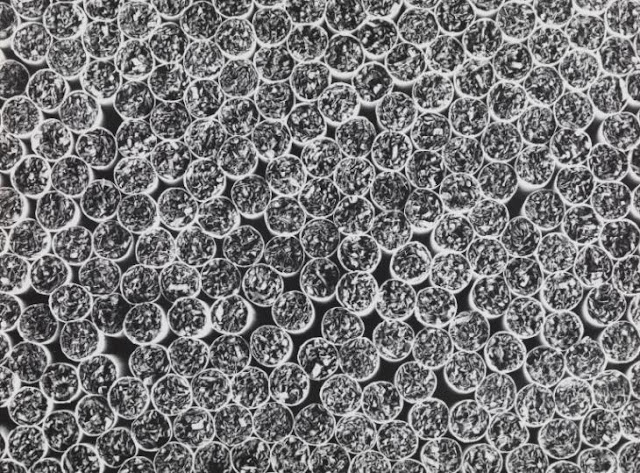

Germaine Luise Krull

Germaine Luise Krull ( November

1897 – July 1985) was a photographer, political activist, and hotel owner.

Her nationality has been

categorized as German, French, and Dutch. Described as "an especially

outspoken example" of a group of early 20th-century female photographers who

"could lead lives free from convention", she is best known for

photographically-illustrated books such as her 1928 portfolio Métal.

Krull was politically

active between 1918 and 1921. In 1919 she switched from the Independent Socialist

Party of Bavaria to the Communist Party of Germany, and was arrested and

imprisoned for assisting a Bolshevik emissary's attempted escape to Austria.

She was expelled from

Bavaria in 1920 for her Communist activities, and traveled to Russia with lover

Samuel Levit. After Levit abandoned her in 1921, Krull was imprisoned as an

"anti-Bolshevik" and expelled from Russia.

She lived in Berlin

between 1922 and 1925 where she resumed her photographic career. Among other photographs

Krull produced in Berlin were a series of nudes.

In Paris between 1926 and

1928, Krull became friends with Sonia Delaunay, Robert Delaunay, Eli Lotar,

André Malraux, Colette, Jean Cocteau, André Gide and others; her commercial

work consisted of fashion photography, nudes, and portraits. During this period

she published the portfolio Métal (1928) which concerned "the essentially

masculine subject of the industrial landscape."

Krull shot the

portfolio's 64 black-and-white photographs in Paris, Marseille, and Holland

during approximately the same period as Ivens was creating his film De Brug "The

Bridge") in Rotterdam, and the two artists may have influenced each other.

The portfolio's subjects range from bridges,

buildings (e.g., the Eiffel Tower), and ships to bicycle wheels; it can be read

as either a celebration of machines or a criticism of them

Many of the photographs

were taken from dramatic angles, and overall the work has been compared to that

of László Moholy-Nagy and Alexander Rodchenko. In 1999–2004 the portfolio was

selected as one of the most important photobooks in history.

Closest ever, mysterious 'fast radio burst' found 30,000 light-years from Earth

Magnetar SGR 1935+2154

was discovered in 2014, but April 2020 was when scientists saw it become active

again

By Chris Ciaccia

Fast radio bursts (FRBs)

are often mysterious in nature, but not an uncommon observation in deep space.

However, researchers have discovered the first FRB to emanate from the Milky

Way galaxy, according to a newly published study.

The research details magnetar SGR 1935+2154,

which was discovered in 2014, but it wasn't until April 2020 when scientists

saw it become active again, shooting out radio waves and X-rays at random intervals.

“We’ve never seen a burst

of radio waves, resembling a Fast Radio Burst, from a magnetar before,” the

study's lead author, Sandro Mereghetti of the National Institute for

Astrophysics (INAF–IASF), said in a statement.

This FRB likely comes

from a neutron star, approximately 30,000 light-years from Earth in the

Vulpecula constellation, LiveScience reports. A light-year, which measures

distance in space, is approximately 6 trillion miles.

Mereghetti and the other

researchers detected the FRB using the European Space Agency's (ESA) Integral

satellite on April 28.

The "Burst Alert

System" sent out an alert about the discovery around the world "in

just seconds," which Merghetti said enabled "the scientific community

to act fast and explore this source in more detail.”

Astronomers around the

globe also spotted the "short and extremely bright burst of radio

waves" via the CHIME radio telescope in Canada also on April 28.

Subsequent confirmations came from California and Utah the following day.

“This is the first ever

observational connection between magnetars and Fast Radio Bursts," Mereghetti

added. "It truly is a major discovery, and helps to bring the origin of

these mysterious phenomena into focus.”

The study has been

published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

It's unknown how common

FRBs actually are and why some of them repeat and others do not; most of their

origins are also mysterious in nature.

Some researchers have

speculated they stem from an extraterrestrial civilization. But others,

including the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence Institute, or SETI, have

said that explanation "really doesn't make sense."

They come from all over

space "and arranging cooperative alien behavior when even one-way

communication takes many billions of years seems unlikely — to put it gently,"

SETI wrote in a September 2019 blog post.

First discovered in 2007,

FRBs are relatively new to astronomers and their origins are mysterious.

According to ScienceAlert, some of them can generate as much energy as 500

million suns in a few milliseconds.

In July 2018, an FRB that

hit Earth was nearly 200 megahertz lower than any other radio burst ever

detected.

Jackson Carey Frank

Edited from Wikipedia

Jackson Carey Frank

(March 2, 1943 – March 3, 1999) was an American folk musician. He released his

first and only album in 1965, produced by Paul Simon. After the release of the

record, he was plagued by a series of personal issues, and was diagnosed with

schizophrenia and protracted depression that prevented him from maintaining his

career. He spent his later life homeless and destitute, and died in 1999 of

pneumonia. Though he only released one record, he has been cited as an

influence by many singer-songwriters, including Paul Simon, Sandy Denny, Bert

Jansch and Nick Drake. Rolling Stone journalist David Fricke called Frank

"one of the best forgotten songwriters of the 1960s."

His eponymous 1965 album,

Jackson C. Frank, was produced by Paul Simon while the two of them were living

in England immersed in the burgeoning local folk scene. The album was recorded

in six hours at Levy’s Recording Studio, located at 103 New Bond Street in

London.

Frank was so shy during the recording that he

asked to be shielded by screens so that Paul Simon, Art Garfunkel, and Al

Stewart could not see him, claiming: 'I can't play. You're looking at me.'

The best-known track from

the sessions, "Blues Run the Game", was covered by Simon and Garfunkel,

and later by Wizz Jones, Counting Crows, John Mayer, Mark Lanegan, Headless

Heroes, Colin Meloy, Bert Jansch, Eddi Reader, Laura Marling and Robin Pecknold

(as White Antelope), while Nick Drake also recorded it privately.

The song was also heard

in the 2018 film The Old Man & the Gun, while his song "Milk and

Honey" was heard in the 2003 film The Brown Bunny. "Milk and

Honey" was also covered by Fairport Convention, Nick Drake, and Sandy

Denny, whom he dated for a while. During their relationship, Jackson convinced

Sandy to give up her nursing profession to concentrate on music full time.

Although Frank was well

received in England for a while, in 1966 things took a turn for the worse as

his mental health began to unravel. Frank's mental health declined so

noticeably and completely that in early 1966 he entered St. John’s Hospital in

Lincoln for an evaluation. At the same

time he began to experience writer's block. As his insurance payment was on the

verge of running out he decided to go back to the United States for two years.

When he returned to England in 1968 he seemed a different person to his

friends. His depression, stemming from the childhood trauma of the classroom

fire, had grown worse, and he had completely lost whatever little self-confidence

he once possessed. Al Stewart recalled: He [Frank] proceeded to fall apart

before our very eyes. His style that everyone loved was melancholy, very

tuneful things. He started doing things that were completely impenetrable. They

were basically about psychological angst, played at full volume with lots of

thrashing. I don't remember a single word of them, it just did not work. There was

one review that said he belonged on a psychologist's couch. Then shortly after

that, he hightailed it back to Woodstock again, because he wasn't getting any

work.

While in Woodstock, he

married Elaine Sedgwick, an English former fashion model. They had a son and

later a daughter, Angeline. After his son died of cystic fibrosis, Frank went

into a period of even greater depression and was ultimately committed to a

mental institution. By the early 1970s Frank began to beg aid from friends. In 1975,

Karl Dallas wrote an enthusiastic piece in the British weekly music newspaper

Melody Maker, and in 1978, Frank's 1965 album was re-released as Jackson Again,

with a new cover sleeve, although this did not in the end make his music much

more popular outside of a small number of his fans.

Frank lived with his

parents in Elma, New York, for a few years in the early 1980s. In 1984, his

mother, who had been in hospital for open-heart surgery, returned home to find

Frank missing with no note or forwarding address. Frank had gone to New York

City in a desperate bid to find Paul Simon, but ended up homeless and sleeping

on the sidewalk. During this time he found himself in and out of various

psychiatric institutions.

Frank was treated for

paranoid schizophrenia, a diagnosis that was denied by Frank himself (he

maintained that he was suffering from depression caused by the trauma he had

experienced as a child). Just as Frank's prospects seemed to be at their worst,

a fan from the Woodstock area, Jim Abbott, discovered him in the early 1990s.

Abbott had been discussing music with Mark Anderson, a teacher at the local

college he was attending.

Though he never achieved

fame during his lifetime, his songs have been covered by many well-known

artists.

The Mount

"The

Pelican."

A short

story by Edith Wharton

SHE was very pretty when I first knew her,

with the sweet straight nose and short upper lip of the cameo-brooch divinity,

humanized by a dimple that flowered in her cheek whenever anything was said

which possessed the outward attributes of humor without its intrinsic quality.

For the dear lady was providentially deficient in humor: the least hint of the

real thing clouded her lovely eye like the hovering shadow of an algebraic

problem.

I do not think that nature had meant her to

be "intellectual"; but what can a poor thing do, whose husband has

died of drink when her baby is hardly six months old, and who finds that her

coral necklace and her grandfather's edition of the British Dramatists are

inadequate to the demands of the creditors?

Her mother, the celebrated Irene Astarte

Pratt, had written a poem in blank verse on "The Fall of Man"; one of

her aunts was dean of a girl's college; another had translated Euripides --

with such a family, the poor child's fate was sealed in advance. The only way

of paying her husband's debts and keeping the baby clothed was to be

intellectual; and, after some hesitation as to the form that her mental

activity was to take, it was unanimously decided that she was to give lectures.

They began by being drawing-room lectures.

The first time I saw her she was standing by the piano, against a flippant

background of Dresden china and photographs, telling a roomful of women

preoccupied with their spring bonnets all that she thought she knew about Greek

art. The ladies assembled to hear her had given me to understand that she was

"doing it for the baby," and this fact, together with the shortness

of her upper lip and the bewildering co-operation of her dimple, disposed me to

listen leniently to her dissertation. Happily, at that time Greek art was

still, if I may use the phrase, easily handled; it was as simple as walking

down a museum-gallery lined with pleasant familiar Venuses and Apollos. All the

later complications -- the archaic and archaistic conundrums; the influences of

Assyria and Asia Minor; the conflicting attributions and the wrangles of the

erudite -- still slumbered in the bosom of the future "scientific

critic." Greek art in those days began with Phidias and ended with the

Apollo Belvedere; and a child could travel from one to the other without danger

of losing its way.

Mrs. Amyot had two fatal gifts: a capacious

but inaccurate memory, and an extraordinary fluency of speech. There was

nothing that she did not remember -- wrongly; but her halting facts were

swathed in so many layers of cotton-wool eloquence that their infirmities were

imperceptible to her friendly critics. Besides, she had been taught Greek by

the aunt who had translated Euripides; and the mere sound of the ais and ois

which she now and then not unskilfully let slip (correcting herself, of course,

with a start, and indulgently mistranslating the phrase), struck awe to the

hearts of ladies whose only "accomplishment" was French -- if you

didn't speak too quickly.

I had then but a momentary glimpse of Mrs.

Amyot, but a few months later I came upon her again in the New England

university town where the celebrated Irene Astarte Pratt lived on the summit of

a local Parnassus, with lesser muses and college professors respectfully grouped

on the lower ledges of the sacred declivity. Mrs. Amyot, who, after her

husband's death, had returned to the maternal roof (even during her father's

lifetime the roof had been distinctively maternal), Mrs. Amyot, thanks to her

upper lip, her dimple, and her Greek, was already ensconced in a snug hollow of

the Parnassian slope.

After the lecture was over it happened that

I walked home with Mrs. Amyot. Judging from the incensed glances of two or

three learned gentlemen who were hovering on the door-step when we emerged, I

inferred that Mrs. Amyot, at that period, did not often walk home alone; but I

doubt whether any of my discomfited rivals, whatever his claims to favor, was

ever treated to so ravishing a mixture of shyness and self-abandonment, of sham

erudition and real teeth and hair, as it was my privilege to enjoy. Even at the

incipience of her public career Mrs. Amyot had a tender eye for strangers, as

possible links with successive centres of culture to which in due course the torch

of Greek art might be handed on.

She began by telling me that she had never

been so frightened in her life. She knew, of course, how dreadfully learned I

was, and when, just as she was going to begin, her hostess had whispered to her

that I was in the room, she had felt ready to sink through the floor. Then

(with a flying dimple) she had remembered Emerson's line -- wasn't it

Emerson's? -- that beauty is its own excuse for seeing, and that had made her

feel a little more confident, since she was sure that no one saw beauty more

vividly than she -- as a child she used to sit for hours gazing at an Etruscan

vase on the bookcase in the library while her sisters played with their dolls

-- and if seeing beauty was the only excuse one needed for talking about it,

why, she was sure I would make allowances and not be too critical and

sarcastic, especially if, as she thought probable, I had heard of her having

lost her poor husband, and how she had to do it for the baby.

Being over-abundantly assured of my sympathy

on these points, she went on to say that she had always wanted so much to

consult me about her lectures. Of course, one subject wasn't enough (this view

of the limitations of Greek art as a "subject" gave me a startling

idea of the rate at which a successful lecturer might exhaust the universe);

she must find others; she had not ventured on any as yet, but she had thought

of Tennyson -- didn't I love Tennyson? She worshipped him so that she was sure

she could help others to understand him; or what did I think of a

"course" on Raphael or Michaelangelo -- or on the heroines of

Shakespeare? There were some fine steel-engravings of Raphael's Madonnas and of

the Sistine ceiling in her mother's library, and she had seen Miss Cushman in

several Shakespearian roles, so that on these subjects also she felt qualified

to speak with authority.

When we reached her mother's door she begged

me to come in and talk the matter over; she wanted me to see the baby -- she

felt as though I should understand her better if I saw the baby -- and the

dimple flashed through a tear.

The fear of encountering the author of

"The Fall of Man," combined with the opportune recollection of a

dinner engagement, made me evade this appeal with the promise of returning on

the morrow. On the morrow, I left too early to redeem my promise; and for

several years afterward I saw no more of Mrs. Amyot.

My calling at that time took me at irregular

intervals from one to another of our larger cities, and as Mrs. Amyot was also

peripatetic it was inevitable that sooner or later we should cross each other's

path. It was therefore without surprise that, one snowy afternoon in Boston, I

learned from the lady with whom I chanced to be lunching that, as soon as the

meal was over, I was to be taken to hear Mrs. Amyot lecture.

"On Greek art?" I suggested.

"Oh, you've heard her then? No, this is

one of the series called 'Homes and Haunts of the Poets.' Last week we had

Wordsworth and the Lake Poets, to-day we are to have Goethe and Weimar. She is

a wonderful creature -- all the women of her family are geniuses. You know, of

course, that her mother was Irene Astarte Pratt, who wrote a poem on 'The Fall

of Man'; N. P. Willis called her the female Milton of America. One of Mrs.

Amyot's aunts has translated Eurip -- "

"And is she as pretty as ever?" I

irrelevantly interposed.

My hostess stared. "She is excessively

modest and retiring. She says it is actual suffering for her to speak in

public. You know she only does it for the baby."

Punctually at the hour appointed, we took

our seats in a lecture-hall full of strenuous females in ulsters. Mrs. Amyot

was evidently a favorite with these austere sisters, for every corner was

crowded, and as we entered a pale usher with an educated mispronunciation was

setting forth to several dejected applicants the impossibility of supplying

them with seats.

Our own were happily so near the front that

when the curtains at the back of the platform parted, and Mrs. Amyot appeared,

I was at once able to establish a rapid comparison between the lady placidly

dimpling to the applause of her public and the shrinking drawing-room orator of

my earlier recollections.

Mrs. Amyot was as pretty as ever, and there

was the same curious discrepancy between the freshness of her aspect and the

staleness of her theme, but something was gone of the blushing unsteadiness

with which she had fired her first random shots at Greek art. It was not that

the shots were less uncertain, but that she now had an air of assuming that,

for her purpose, the bull's-eye was everywhere, so that there was no need to be

flustered in taking aim. This assurance had so facilitated the flow of her

circumlocutious diction that, as I listened, I had a curious sense that she was

performing a trick analogous to that of the conjuror who pulls hundreds of

yards of white paper out of his mouth. From a large assortment of stock

adjectives she chose, with unerring deftness and rapidity, the one which taste

and discrimination would most surely have rejected, fitting out her subject, as

it were, with a whole wardrobe of slop-shot epithets irrelevant in cut and

size. To the invaluable knack of not disturbing the association of ideas in her

audience, she added the gift of what may be called a confidential manner -- so

that her fluent generalizations about Goethe and his place in literature (the

lecture was, of course, manufactured out of Lewes's book) had the flavor of

personal experience, of views sympathetically exchanged with her audience on

the best way of knitting children's socks, or of putting up preserves for the

winter. It was, I am sure, to this personal accent -- the moral equivalent of

her dimple -- that Mrs. Amyot owed her prodigious, her irrational success. It

was her art of transposing second-hand ideas into first-hand emotions that so

endeared her to her feminine listeners.

To anyone not in search of

"documents" Mrs. Amyot's success was hardly of a kind to make her

more interesting, and my curiosity flagged with the growing conviction that the

"suffering" entailed upon her by public speaking was at most a

retrospective pang. I was sure that, as a matter of fact, she had reached the

point of measuring and enjoying her effects, of deliberately manipulating her

public; and there must indeed have been a certain exhilaration in attaining

results so considerable by means involving so little conscious effort. Mrs.

Amyot's art was simply an extension of coquetry: she flirted with her audience.

In this mood of enlightened skepticism I

responded but languidly to my hostess's suggestion that I should go with her

that evening to see Mrs. Amyot. The aunt who had translated Euripides was at

home on Saturday evenings, and one met "thoughtful" people there, my

hostess explained: it was one of the intellectual centres of Boston. My mood

remained distinctly resentful of any connection between Mrs. Amyot and

intellectuality, and I declined to go; but the next day I met Mrs. Amyot in the

street.

She stopped me reproachfully. She had heard

that I was in Boston; why had I not come last night? She had been told that I

was at her lecture; and it had frightened her -- yes, really, almost as much as

years ago in Hillbridge. She never could get over that stupid shyness, and the

whole business was as distasteful to her as ever; but what could she do? There

was the baby -- he was a big boy now, and boys were so expensive! But did I

really think she had improved the least little bit? And why wouldn't I come

home with her now, and see the boy, and tell her frankly what I had thought of

the lecture? She had plenty of flattery -- people were so kind, and every one

knew that she did it for the baby -- but what she felt the need of was

criticism, severe, discriminating criticism like mine -- oh, she knew that I

was dreadfully discriminating!

I went home with her and saw the boy. In the

early heat of her Tennyson-worship Mrs. Amyot had christened him Lancelot, and

he looked it. Perhaps, however, it was his black velvet dress and the

exasperating length of his yellow curls, together with the fact of his having

been taught to recite Browning to visitors, that raised to fever heat the

itching of my palms in his Infant-Samuel-like presence. I have since had reason

to think that he would have preferred to be called Billy, and to hunt cats with

the other boys in the block: his curls and his poetry were simply another

outlet for Mrs. Amyot's irrepressible coquetry.

But if Lancelot was not genuine, his

mother's love for him was. It justified everything -- the lectures were for the

baby, after all. I had not been ten minutes in the room before I was pledged to

help Mrs. Amyot to carry out her triumphant fraud. If she wanted to lecture on

Plato she should -- Plato must take his chance like the rest of us! There was

no use, of course, in being "discriminating." I preserved sufficient

reason to avoid that pitfall, but I suggested "subjects" and made

lists of books for her with a fatuity that became more obvious as time attenuated

the remembrance of her smile; I even remember thinking that some men might have

cut the knot by marrying her, but I handed over Plato as a hostage, and escaped

by the afternoon train.

The next time I saw her was in New York,

when she had become so fashionable that it was a part of the whole duty of

woman to be seen at her lectures. The lady who suggested that of course I ought

to go and hear Mrs. Amyot, was not very clear about anything except that she

was perfectly lovely, and had had a horrid husband, and was doing it to support

her boy. The subject of the discourse (I think it proved to be on Ruskin) was

clearly of minor importance, not only to my friend, but to the throng of

well-dressed and absent-minded ladies who rustled in late, dropped their muffs

and pocket-books, and undisguisedly lost themselves in the study of each

other's apparel. They received Mrs. Amyot with warmth, but she evidently

represented a social obligation like going to church, rather than any more

personal interest; in fact, I suspect that every one of the ladies would have

remained away, had it been ascertainable that none of the others were coming.

Whether Mrs. Amyot was disheartened by the

lack of sympathy between herself and her hearers, or whether the sport of

arousing it had become a task, she certainly imparted her platitudes with less

convincing warmth than of old. Her voice had the same confidential inflections,

but it was like a voice reproduced by a gramophone: the real woman seemed far

away. She had grown stouter without losing her dewy freshness, and her smart

gown might have been taken to indicate either the potentialities of a settled

income, or a politic concession to the taste of her hearers. As I listened I

reproached myself for ever having suspected her of self-deception in declaring

that she took no pleasure in her work. I was sure now that she did it only for

Lancelot, and judging from the size of her audience and the price of the

tickets I concluded that Lancelot must be receiving a liberal education.

I was living in New York that winter, and in

the rotation of dinners I found myself one evening at Mrs. Amyot's side. The

dimple came out at my greeting as punctually as a cuckoo in a Swiss clock and I

detected the same automatic quality in the tone in which she made her usual

pretty demand for advice. She was like a musical-box charged with popular airs.

They succeeded one another with breathless rapidity, but there was a moment

after each when the cylinders scraped and whizzed.

Mrs. Amyot, as I found when I called upon

her, was living in a pleasant flat, with a sunny sitting-room full of flowers

and a tea-table that had the air of expecting visitors. She owned that she had

been ridiculously successful. It was delightful, of course, on Lancelot's

account. Lancelot had been sent to the best school in the country, and if

things went well and people didn't tire of his silly mother he was to go to

Harvard afterward. During the next two or three years Mrs. Amyot kept her flat

in New York, and radiated art and literature upon the suburbs. I saw her now

and then, always stouter, better dressed, more successful and more automatic:

she had become a lecturing-machine.

I went abroad for a year or two and when I

came back she had disappeared. I asked several people about her, but life had

closed over her. She had been last heard of as lecturing -- still lecturing --

but no one seemed to know when or where.

It was in Boston that I found her at last,

forlornly swaying to the oscillations of an overhead strap in a crowded trolley-car.

Her face had so changed that I lost myself in a startled reckoning of the time

that had elapsed since our parting. She spoke to me shyly, as though aware of

my hurried calculation, and conscious that in five years she ought not to have

altered so much as to upset my notion of time. Then she seemed to set it down

to her dress, for she nervously gathered her cloak over a gown that asked only

to be concealed, and shrank into a vacant seat behind the line of prehensile

bipeds blocking the aisle of the car.

It was perhaps because she so obviously

avoided me that I felt for the first time that I might be of use to her; and

when she left the car I made no excuse for following her.

She said nothing of needing advice and did

not ask me to walk home with her, concealing, as we talked, her transparent

preoccupations under the mask of a sudden interest in all that I had been doing

since she had last seen me. Of what concerned her, I learned only that Lancelot

was well and that for the present she was not lecturing -- she was tired and

her doctor had ordered her to rest. On the doorstep of a shabby house she

paused and held out her hand. She had been so glad to see me and perhaps if I

were in Boston again -- the tired dimple, as it were, bowed me out and closed

the door upon the conclusion of the phrase.

Two or three weeks later, at my club in New

York, I found a letter from her. In it she owned that she was troubled, that of

late she had been unsuccessful, and that, if I chanced to be coming back to

Boston, and could spare her a little of that invaluable advice which -- . A few

days later the advice was at her disposal.

She told me frankly what had happened. Her

public had grown tired of her. She had seen it coming on for some time, and was

shrewd enough in detecting the causes. She had more rivals than formerly --

younger women, she admitted, with a smile which could still afford to be

generous -- and then her audiences had grown more critical and consequently

more exacting. Lecturing -- as she understood it -- used to be simple enough.

You chose your topic -- Raphael, Shakespeare, Gothic Architecture, or some such

big familiar "subject" -- and read up about it for a week or so at

the Athenaeum or the Astor Library, and then told your audience what you had

read. Now, it appeared, that simple process was no longer adequate. People had

tired of familiar "subjects"; it was the fashion to be interested in

things that one hadn't always known about -- natural selection, animal

magnetism, sociology and comparative folk-lore; while, in literature, the

demand had become equally difficult to meet, since Matthew Arnold had

introduced the habit of studying the "influence" of one author on

another. She had tried lecturing on influences, and had done very well as long

as the public was satisfied with the tracing of such obvious influences as that

of Turner on Ruskin, of Schiller on Goethe, of Shakespeare on the English

drama; but such investigations had soon lost all charm for her

too-sophisticated audiences, who now demanded either that the influence or the

influenced should be absolutely unknown, or that there should be no perceptible

connection between the two. The zest of the performance lay in the measure of

ingenuity with which the lecturer established a relation between two people who

had probably never heard of each other, much less read each other's works. A

pretty Miss Williams with red hair had, for instance, been lecturing with great

success on the influence of the Rosicrucians upon the poetry of Keats, while

somebody else had given a "course" on the influence of St. Thomas

Aquinas upon Professor Huxley.

Mrs. Amyot, warmed by my evident

participation in her distress, went on to say that the growing demand for

evolution was what most troubled her. Her grandfather had been a pillar of the

Presbyterian ministry, and the idea of her lecturing on Darwin or Herbert

Spencer was deeply shocking to her mother and aunts. In one sense the family

had staked its literary as well as its spiritual hopes on the literal

inspiration of Genesis: what became of "The Fall of Man" in the light

of modern exegesis?

The upshot of it was that she had ceased to

lecture because she could no longer sell tickets enough to pay for the hire of

a lecture-hall; and as for the managers, they wouldn't look at her. She had

tried her luck all through the Eastern States and as far South as Washington;

but it was of no use, and unless she could get hold of some new subjects -- or,

better still, of some new audiences -- she must simply go out of the business.

That would mean the failure of all she had worked for, since Lancelot would

have to leave Harvard. She paused, and wept some of the unbecoming tears that

spring from real grief. Lancelot, it appeared, was to be a genius. He had

passed his opening examinations brilliantly; he had "literary gifts";

he had written beautiful poetry, much of which his mother had copied out in

reverentially slanting characters upon the pages of a velvet-bound volume which

she drew from a locked drawer.

Lancelot's verse struck me as nothing more

alarming than growing-pains; but it was not to learn this that she had summoned

me. What she wanted was to be assured that he was worth working for, an

assurance which I managed to convey by the simple strategy of remarking that

the poems reminded me of Swinburne -- and so they did, as well as of Browning, Tennyson,

Rossetti, William Morris, and all the other poets who supply young authors with

original inspirations.

This point being satisfactorily established,

it remained to be decided by what means his mother was, in the French phrase,

to pay herself the luxury of a poet. It was obvious that this indulgence could

be bought only with counterfeit coin, and that the one way of helping Mrs.

Amyot was to become a party to the circulation of such currency. My fetish of

intellectual integrity went down like a ninepin before the appeal of a woman no

longer young and distinctly foolish, but full of those dear contradictions and

irrelevances that will always make flesh and blood prevail against a syllogism.

When I took leave of Mrs. Amyot I had promised her a dozen letters to Western

universities and had half-pledged myself to sketch out for her a lecture on the

reconciliation of science and religion.

In the West she achieved a success which for

a year or more embittered my perusal of the morning papers. The fascination

which lures the murderer back to the scene of his crime drew my eye to every

paragraph celebrating Mrs. Amyot's last brilliant lecture on the influence of

something upon somebody; and her own letters -- she overwhelmed me with them --

spared me no detail of the entertainment given in her honor by the Palimpsest

Club of Omaha or of her reception at the University of Leadville. The college

professors were especially kind: she assured me that she had never before met

with such discriminating sympathy. I winced under the adjective, which cast a

sudden light upon the vast machinery of fraud that I had set in motion. All

over my native land, men of hitherto unblemished integrity were conniving with

me in urging their friends to go and hear Mrs. Amyot lecture on the

reconciliation of science and religion! My only hope was that, somewhere among

the number of my accomplices, Mrs. Amyot might find one who would marry her in

the defense of his literary convictions.

None, apparently, resorted to such heroic measures;

for about two years later I was startled by the announcement that Mrs. Amyot

was lecturing in Trenton, N. J., on modern theosophy in the light of the Vedas.

The following week she was at Newark, discussing Schopenhauer in the light of

recent psychology. The week after that I was on the deck of an ocean steamer,

reconsidering my share in Mrs. Amyot's triumphs with the impartiality with

which one views an episode that is being left behind at the rate of twenty

knots an hour. After all, I had been helping a mother to educate her son.

The next decade of my life was spent in

Europe, and when I came home the recollection of Mrs. Amyot had become as

inoffensive as one of those pathetic ghosts who are said to strive in vain to

make themselves visible to the living. I did not even notice the fact that I no

longer heard her spoken of; she had dropped like a dead leaf from the bough of

memory.

A year or two after my return I was

condemned to one of the worst punishments that a worker can undergo -- an enforced

holiday. The doctors who pronounced the inhuman sentence decreed that it should

be worked out in the South, and for a whole winter I carried my cough, my

thermometer and my idleness from one fashionable orange-grove to another. In

the vast and melancholy sea of my dis-occupation I clutched like a drowning man

at any human driftwood within reach. I took a critical and depreciatory

interest in the coughs, the thermometers and the idleness of my

fellow-sufferers; but to the healthy, the occupied, the transient I clung with

undiscriminating enthusiasm.

In no other way can I explain, as I look

back upon it, the importance which I attached to the leisurely confidences of a

new arrival with a brown beard who, tilted back at my side on a hotel veranda

hung with roses, imparted to me one afternoon the simple annals of his past.

There was nothing in the tale to kindle the most inflammable imagination, and

though the man had a pleasant frank face and a voice differing agreeably from

the shrill inflections of our fellow-lodgers, it is probable that under

different conditions his discursive history of successful business ventures in

a Western city would have affected me somewhat in the manner of a lullaby.

Even at the time I was not sure that I liked

his agreeable voice. It had a sonorous assertiveness out of keeping with the

humdrum character of his recital, as though a breeze engaged in shaking out a

table-cloth should have fancied itself inflating a banner. But this criticism

may have been a mere mark of my own fastidious humor, for the man seemed a

simple fellow, satisfied with his middling fortunes, and already (he was not

much past thirty) deep-sunk in conjugal content.

He had just entered upon an anecdote

connected with the cutting of his eldest boy's teeth, when a lady whom I knew,

returning from her late drive, paused before us for a moment in the twilight,

with the smile which is the feminine equivalent of beads to savages.

"Won't you take a ticket?" she

said, sweetly.

Of course I would take a ticket -- but for

what? I ventured to inquire.

"Oh, that's so good of you -- for the

lecture this evening. You needn't go, you know; we are none of us going; most

of us have been through it already at Aiken and at Saint Augustine and at Palm

Beach. I've given away my tickets to some new people who've just come from the

North, and some of us are going to send our maids, just to fill up the

room."

"And may I ask to whom you are going to

pay this delicate attention?"

"Oh, I thought you knew -- to poor Mrs.

Amyot. She's been lecturing all over the South this winter; she's simply

haunted me ever since I left New York -- and we had six weeks of her at Bar

Harbor last summer! One has to take tickets, you know, because she's a widow

and does it for her son -- to pay for his education. She's so plucky and nice

about it, and talks about him in such a touching unaffected way, that everybody

is sorry for her, and we all simply ruin ourselves in tickets. I do hope that

boy's nearly educated!"

"Mrs. Amyot? Mrs. Amyot?" I

repeated. "Is she still educating her son?"

"Oh, do you know about her? Has she

been at it long? There's some comfort in that, for I suppose when the boy's

provided for the poor thing will be able to take a rest -- and give us

one!"

She laughed and extended her hand.

"Here's your ticket. Did you say tickets -- two? Oh, thanks. Of course you

needn't go."

"But I mean to go. Mrs. Amyot is an old

friend of mine."

"Do you really? That's awfully good of

you. Perhaps I'll go too if I can persuade Charlie and the others to come. And

I wonder" -- in a well-directed aside -- "if your friend -- ?"

I telegraphed her under cover of the dusk

that my friend was of too recent standing to be drawn into her charitable

toils, and she masked her mistake under a rattle of friendly adjurations not to

be late, and to be sure to keep a seat for her, as she had quite made up her

mind to go even if Charlie and the others wouldn't.

The flutter of her skirts subsided in the

distance, and my neighbor, who had half turned away to light a cigar, made no

effort to reopen the conversation. At length, fearing that he might have

overheard the allusion to himself, I ventured to ask if he were going to the

lecture that evening.

"Much obliged -- I have a ticket,"

he said, abruptly.

This struck me as in such bad taste that I

made no answer; and it was he who spoke next.

"Did I understand you to say that you

were an old friend of Mrs. Amyot's?"

"I think I may claim to be, if it is

the same Mrs. Amyot whom I had the pleasure of knowing many years ago. My Mrs.

Amyot used to lecture too -- "

"To pay for her son's education?"

"I believe so."

"Well -- see you later."

He got up and walked into the house.

In the hotel drawing-room that evening there

was but a meagre sprinkling of guests, among whom I discovered my brown-bearded

friend sitting alone on a sofa, with his head against the wall. It was

certainly not curiosity to see Mrs. Amyot which had impelled him to attend the

performance, for it would have been impossible for him, without shifting his

position, to command the improvised platform at the end of the room. When I

looked at him he seemed lost in contemplation of the chandelier.

The lady from whom I had purchased my

tickets fluttered in late, unattended by Charlie and the others, and assuring

me that she should scream if we had the lecture on Ibsen -- she had heard it

three times already that winter. A glance at the programme reassured her: it

informed us (in the lecturer's own slanting hand) that Mrs. Amyot was to

lecture on the Cosmogony.

After a long pause, during which the small

audience coughed and moved its chairs and showed signs of regretting that it

had come, the door opened, and Mrs. Amyot stepped upon the platform. Ah, poor

lady!

Someone said "Hush!" the coughing

and chair-shifting subsided, and she began.

It was like looking at one's self early in

the morning in a cracked mirror. I had no idea that I had grown so old. As for

Lancelot, he must have a beard. A beard? The word struck me, and without

knowing why I glanced across the room at my bearded friend on the sofa. Oddly

enough he was looking at me, with a half-defiant, half-sullen expression; and

as our glances crossed, and his fell, the conviction came to me that he was

Lancelot.

I don't remember a word of the lecture; and

yet there were enough of them to have filled a good-sized dictionary. The

stream of Mrs. Amyot's eloquence had become a flood: one had the despairing

sense that she had sprung a leak, and that until the plumber came there was

nothing to be done about it.

The plumber came at length, in the shape of

a clock striking ten; my companion, with a sigh of relief, drifted away in

search of Charlie and the others; the audience scattered with the precipitation

of people who had discharged a duty; and, without surprise, I found my brown-bearded

acquaintance at my elbow.

We stood alone in the big bare-floored room,

under the flaring chandelier.

"I think you told me this afternoon

that you were an old friend of Mrs. Amyot's?" he began awkwardly.

I assented.

"Will you come in and see her?"

"Now? I shall be very glad to, if --

"

"She's ready; she's expecting

you," he interposed.

He offered no further explanation, and I

followed him in silence. He led me down the long corridor, and pushed open the

door of a sitting-room.

"Mother," he said, closing the

door after we had entered, "here's the gentleman who says he used to know

you."

Mrs. Amyot, who sat in an easy-chair

stirring a cup of bouillon, looked up with a start. She had evidently not seen

me in the audience, and her son's description had failed to convey my identity.

I saw a frightened look in her eyes; then, like a frost flower on a

window-pane, the dimple expanded on her wrinkled cheek, and she held out her

hand to me.

"I'm so glad," she said, "so

glad!"

She turned to her son, who stood watching

us. "You must have told Lancelot all about me -- you've known me so

long!"

"I haven't had time to talk to your son

-- since I knew he was your son," I explained.

Her brow cleared. "Then you haven't had

time to say anything very dreadful?" she said, with a laugh.

"It is he who has been saying dreadful

things," I returned, trying to fall in with her tone.

I saw my mistake. "What things?"

she faltered.

"Making me feel how old I am by telling

me about his children."

"My grandchildren!" she exclaimed,

with a blush.

"Well, if you choose to put it

so."

She laughed again, vaguely, and was silent.

I hesitated a moment, and then put out my hand.

"I see that you are tired. I shouldn't have

ventured to come in at this hour if your son -- "

The son stepped between us. "Yes, I

asked him to come," he said to his mother, in his clear self-assertive

voice. " I haven't told him anything yet; but you've got to -- now. That's

what I brought him for."

His mother straightened herself, but I saw

her eye waver.

"Lancelot -- " she began.

"Mr. Amyot," I said, turning to

the young man, "if your mother will allow me to come back to-morrow, I

shall be very glad -- "

He struck his hand hard against the table on

which he was leaning.

"No, sir! It won't take long, but it's

got to be said now."

He moved nearer to his mother, and I saw his

lip twitch under his beard. After all, he was younger and less sure of himself

than I had fancied.

"See here, mother," he went on,

"there's something here that's got to be cleared up, and as you say this

gentleman is an old friend of yours it had better be cleared up in his

presence. Maybe he can help explain it -- and if he can't, it's got to be

explained to him."

Mrs. Amyot's lips moved, but she made no

sound. She glanced at me helplessly and reseated herself. My early inclination

to thrash Lancelot was beginning to reassert itself. I took up my hat and moved

toward the door.

"Mrs. Amyot is certainly under no

obligation to explain anything whatever to me," I said, curtly.

"Well! She's under an obligation to me,

then -- to explain something in your presence." He turned to her again.

"Do you know what the people in this hotel are saying? Do you know what he

thinks -- what they all think? That you're doing this lecturing to support me

-- to pay for my education! They say you go round telling them so. That's what

they buy the tickets for -- they do it out of charity. Ask him if it isn't what

they say -- ask him if they weren't joking about it on the piazza before

dinner. The others think I'm a little boy, but he's known you for years, and he

must have known how old I was. He must have known it wasn't to pay for my

education!"

He stood before her with his hands clenched,

the veins beating in his temples. She had grown very pale, and her cheeks

looked hollow. When she spoke her voice had an odd click in it.

"If -- if these ladies and gentlemen

have been coming to my lectures out of charity, I see nothing to be ashamed of

in that -- " she faltered.

"If they've been coming out of charity

to me," he retorted, "don't you see you've been making me a party to

a fraud? Isn't there any shame in that?" His forehead reddened.

"Mother! Can't you see the shame of letting people think that I was a d --

-beat, who sponged on you for my keep? Let alone making us both the

laughing-stock of every place you go to!"

"I never did that, Lancelot!"

"Did what?"

"Made you a laughing-stock -- "

He stepped close to her and caught her

wrist.

"Will you look me in the face and swear

you never told people that you were doing this lecturing business to support

me?"

There was a long silence. He dropped her

wrist, and she lifted a limp handkerchief to her frightened eyes. "I did

do it -- to support you -- to educate you" -- she sobbed.

"We're not talking about what you did

when I was a boy. Everybody who knows me knows I've been a grateful son. Have I

ever taken a penny from you since I left college ten years ago?"

"I never said you had! How can you

accuse your mother of such wickedness, Lancelot?"

"Have you never told anybody in this

hotel -- or anywhere else in the last ten years -- that you were lecturing to

support me? Answer me that!"

"How can you," she wept,

"before a stranger?"

"Haven't you said such things about me

to strangers?" he retorted.

"Lancelot!"

"Well -- answer me, then. Say you

haven't, mother!" His voice broke unexpectedly and he took her hand with a

gentler touch. "I'll believe anything you tell me," he said, almost

humbly.

She mistook his tone and raised her head

with a rash clutch at dignity.

"I think you had better ask this

gentleman to excuse you first."

"No, by God, I won't!" he shouted.

"This gentleman says he knows all about you and I mean him to know all

about me too. I don't mean that he or anybody else under this roof shall go on

thinking for another twenty-four hours that a cent of their money has ever gone

into my pockets since I was old enough to shift for myself. And he sha'n't

leave this room till you've made that clear to him."

He stepped back as he spoke and put his

shoulders against the door.

"My dear young gentleman," I said,

politely, "I shall leave this room exactly when I see fit to do so -- and

that is now. I have already told you that Mrs. Amyot owes me no explanation of

her conduct."

"But I owe you an explanation of mine

-- you and every one who has bought a single one of her lecture tickets. Do you

suppose a man who's been through what I went through while that woman was

talking to you in the porch before dinner is going to hold his tongue, and not

attempt to justify himself? No decent man is going to sit down under that sort

of thing. It's enough to ruin his character. If you're my mother's friend, you

owe it to me to hear what I've got to say."

He pulled out his handkerchief and wiped his

forehead.

"Good God, mother!" he burst out

suddenly, "what did you do it for? Haven't you had every thing you wanted

ever since I was able to pay for it? Haven't I paid you back every cent you

spent on me when I was in college? Have I ever gone back on you since I was big

enough to work?" He turned to me with a laugh. "I thought she did it

to amuse herself -- and because there was such a demand for her lectures. Such

a demand! That's what she always told me. When we asked her to come out and

spend this winter with us in Minneapolis, she wrote back that she couldn't

because she had engagements all through the South, and her manager wouldn't let

her off. That's the reason why I came all the way on here to see her. We

thought she was the most popular lecturer in the United States, my wife and I

did! We were awfully proud of it too, I can tell you." He dropped into a

chair, still laughing.

"How can you, Lancelot, how can

you!" His mother, forgetful of my presence, was clinging to him with

tentative caresses. "When you didn't need the money any longer I spent it

all on the children -- you know I did."

"Yes, on lace christening dresses and

life-size rocking-horses with real manes! The kind of thing that children can't

do without."

"Oh, Lancelot, Lancelot -- I loved them

so! How can you believe such falsehoods about me?"

"What falsehoods about you?"

"That I ever told anybody such dreadful

things?"

He put her back gently, keeping his eyes on

hers. "Did you never tell anybody in this house that you were lecturing to

support your son?"

Her hands dropped from his shoulders, and

she flashed round upon me in sudden anger.

"I know what I think of people who call

themselves friends and who come between a mother and her son!"

"Oh, mother, mother!" he groaned.

I went up to him and laid my hand on his

shoulder.

"My dear man," I said, "don't

you see the uselessness of prolonging this?"

"Yes, I do," he answered,

abruptly, and before I could forestall his movement he rose and walked out of

the room.

There was a long silence, measured by the

decreasing reverberations of his footsteps down the wooden floor of the

corridor.

When they ceased I approached Mrs. Amyot,

who had sunk into her chair. I held out my hand and she took it without a trace

of resentment on her ravaged face.

"I sent his wife a seal-skin jacked at

Christmas!" she said, with the tears running down her cheeks.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)