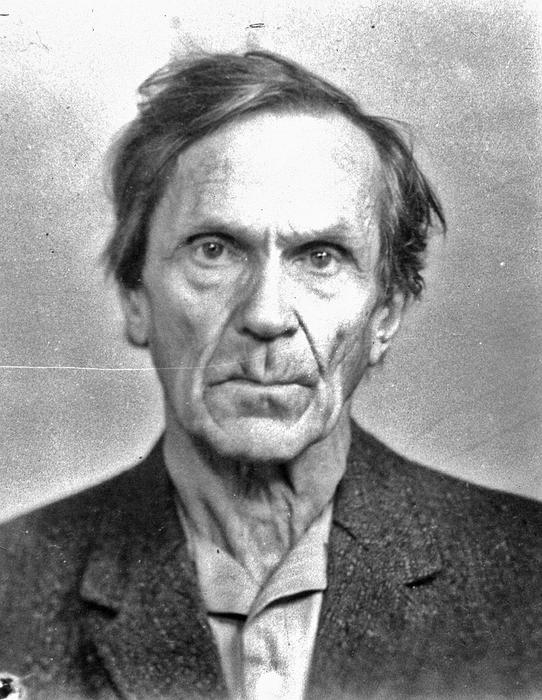

Varlam Tikhonovich Shalamov (

June 18, 1907 – January 17, 1982), was a Russian writer, journalist, poet and

Gulag survivor. He spent much of the period from 1937 to 1951 imprisoned in

forced-labor camps in the arctic region of Kolyma, due in part to his having

supported Leon Trotsky and praised the anti-Soviet writer Ivan Bunin. In 1946,

near death, he became a medical assistant while still a prisoner. He remained

in that role for the duration of his sentence, then for another two years after

being released, until 1953. From 1954 to 1978, he wrote a set of short stories

about his experiences in the labor camps, which were collected and published in

six volumes, collectively known as Kolyma Tales. These books were initially

published in the West, in English translation, starting in the 1960s; they were

eventually published in the original Russian, but only became officially

available in the Soviet Union in 1987, in the post-glasnost era. The Kolyma

Tales are considered Shalamov's masterpiece, and "the definitive

chronicle" of life in the labor camps.

FROM:RUSSIAN

Translated by : John Glad

Envy, like all our feelings, had

been dulled and weakened by hunger. We lacked the strength to experience

emotions, to seek easier work, to walk, to ask, to beg… We envied only our acquaintances,

the ones who had been lucky enough to get office work, a job in the hospital or

the stables – wherever there was none of the long physical labor glorified as

heroic and noble in signs above all the camp gates. In a word, we envied only

Shestakov.

External circumstances alone were

capable of jolting us out of apathy and distracting us from slowly approaching

death. It had to be an external and not an internal force. Inside there was

only an empty scorched sensation, and we were indifferent to everything, making

plans no further than the next day.

Even now I wanted to go back to

the barracks and lie down on the bunk, but instead I was standing at the doors

of the commissary. Purchases could be made only by petty criminals and thieves

who were repeated offenders. The latter were classified as ‘friends of the people’.

There was no reason for us politicals to be there, but we couldn’t take our

eyes off the loaves of bread that were brown as chocolate. Our heads swam from

the sweet heavy aroma of fresh bread that tickled the nostrils. I stood there,

not knowing when I would find the strength within myself to return to the

barracks. I was staring at the bread when Shestakov called to me.

I’d known Shestakov on the

‘mainland’, in Butyr Prison where we were cellmates. We weren’t friends, just

acquaintances. Shestakov didn’t work in the mine. He was an engineer-geologist,

and he was taken into the prospecting group – in the office. The lucky man

barely said hallo to his Moscow acquaintances. We weren’t offended. Everyone

looked out for himself here.

‘Have a smoke,’ Shestakov said

and he handed me a scrap of newspaper, sprinkled some tobacco on it, and lit a

match, a real match. I lit up.

‘I have to talk to you,’

Shestakov said.

‘To me?’

‘Yeah.’

We walked behind the barracks and

sat down on the lip of the old mine. My legs immediately became heavy, but

Shestakov kept swinging his new regulation-issue boots that smelled slightly of

fish grease. His pant legs were rolled up, revealing checkered socks. I stared at

Shestakov’s feet with sincere admiration, even delight. At least one person

from our cell didn’t wear foot rags. Under us the ground shook from dull

explosions; they were preparing the ground for the night shift. Small stones

fell at our feet, rustling like unobtrusive gray birds.

‘Let’s go farther,’ said

Shestakov.

‘Don’t worry, it won’t kill us.

Your socks will stay in one piece.’

‘That’s not what I’m talking

about,’ said Shestakov and swept his index finger along the line of the

horizon. ‘What do you think of all that?’

‘It’s sure to kill us,’ I said.

It was the last thing I wanted to think of.

‘Nothing doing. I’m not willing

to die.’

‘So?’

‘I have a map,’ Shestakov said

sluggishly. ‘I’ll make up a group of workers, take you and we’ll go to Black

Springs. That’s fifteen kilometers from here. I’ll have a pass. And we’ll make

a run for the sea. Agreed?’

He recited all this as

indifferently as he did quickly.

‘And when we get to the sea? What

then? Swim?’

‘Who cares. The important thing

is to begin. I can’t live like this any longer. “Better to die on your feet

than live on your knees.” ’ Shestakov pronounced the sentence with an air of

pomp. ‘Who said that?’

It was a familiar sentence. I

tried, but lacked the strength to remember who had said those words and when.

All that smacked of books was forgotten. No one believed in books.

I rolled up my pants and showed

the breaks in the skin from scurvy.

‘You’ll be all right in the

woods,’ said Shestakov. ‘Berries, vitamins. I’ll lead the way. I know the road.

I have a map.’

I closed my eyes and thought.

There were three roads to the sea from here – all of them five hundred

kilometers long, no less. Even Shestakov wouldn’t make it, not to mention me.

Could he be taking me along as food? No, of course not. But why was he lying?

He knew all that as well as I did. And suddenly I was afraid of Shestakov, the

only one of us who was working in the field in which he’d been trained. Who had

set him up here and at what price? Everything here had to be paid for. Either

with another man’s blood or another man’s life.

‘OK,’ I said, opening my eyes.

‘But I need to eat and get my strength up.’

‘Great, great. You definitely

have to do that. I’ll bring you some… canned food. We can get it…’

There are a lot of canned foods

in the world – meat, fish, fruit, vegetables… But best of all was condensed

milk. Of course, there was no sense drinking it with hot water. You had to eat

it with a spoon, smear it on bread, or swallow it slowly, from the can, eat it

little by little, watching how the light liquid mass grew yellow and how a

small sugar star would stick to the can…

‘Tomorrow,’ I said, choking from

joy. ‘Condensed milk.’

‘Fine, fine, condensed milk.’ And

Shestakov left.

I returned to the barracks and

closed my eyes. It was hard to think. For the first time I could visualize the

material nature of our psyche in all its palpability. It was painful to think,

but necessary.

He’d make a group for an escape

and turn everyone in. That was crystal clear. He’d pay for his office job with

our blood, with my blood. They’d either kill us there, at Black Springs, or

bring us in alive and give us an extra sentence – ten or fifteen years. He

couldn’t help but know that there was no escape. But the milk, the condensed

milk…

I fell asleep and in my ragged

hungry dreams saw Shestakov’s can of condensed milk, a monstrous can with a

sky-blue label. Enormous and blue as the night sky, the can had a thousand

holes punched in it, and the milk seeped out and flowed in a stream as broad as

the Milky Way. My hands easily reached the sky and greedily I drank the thick,

sweet, starry milk.

I don’t remember what I did that

day nor how I worked. I waited. I waited for the sun to set in the west and for

the horses to neigh, for they guessed the end of the work day better than

people.

The work horn roared hoarsely,

and I set out for the barracks where I found Shestakov. He pulled two cans of

condensed milk from his pockets.

I punched a hole in each of the

cans with the edge of an axe, and a thick white stream flowed over the lid on

to my hand.

‘You should punch a second hole

for the air,’ said Shestakov.

‘That’s all right,’ I said,

licking my dirty sweet fingers.

‘Let’s have a spoon,’ said

Shestakov, turning to the laborers surrounding us. Licked clean, ten glistening

spoons were stretched out over the table. Everyone stood and watched as I ate.

No one was indelicate about it, nor was there the slightest expectation that

they might be permitted to participate. None of them could even hope that I

would share this milk with them. Such things were unheard of, and their

interest was absolutely selfless. I also knew that it was impossible not to

stare at food disappearing in another man’s mouth. I sat down so as to be

comfortable and drank the milk without any bread, washing it down from time to

time with cold water. I finished both cans. The audience disappeared – the show

was over. Shestakov watched me with sympathy.

‘You know,’ I said, carefully

licking the spoon, ‘I changed my mind. Go without me.’

Shestakov comprehended immediately and left

without saying a word to me.

It was, of course, a weak,

worthless act of vengeance just like all my feelings. But what else could I do?

Warn the others? I didn’t know them. But they needed a warning. Shestakov

managed to convince five people. They made their escape the next week; two were

killed at Black Springs and the other three stood trial a month later.

Shestakov’s case was considered separately ‘because of production

considerations’. He was taken away, and I met him again at a different mine six

months later. He wasn’t given any extra sentence for the escape attempt; the

authorities played the game honestly with him even though they could have acted

quite differently.

He was working in the prospecting

group, was shaved and well fed, and his checkered socks were in one piece. He

didn’t say hallo to me, but there was really no reason for him to act that way.

I mean, after all, two cans of condensed milk aren’t such a big deal.