(From Wikipedia)

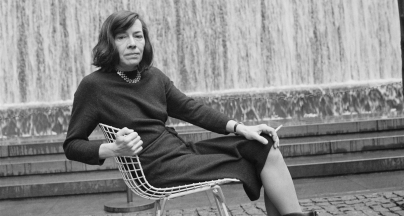

Patricia Highsmith (January 19, 1921 – February 4, 1995) was a novelist and short story writer best known for her psychological thrillers, including her series of five novels featuring the character Tom Ripley. She wrote 22 novels and numerous short stories throughout her career spanning nearly five decades, and her work has led to more than two dozen film adaptations. Her writing derived influence from existentialist literature,[2] and questioned notions of identity and popular morality. She was dubbed "the poet of apprehension" by novelist Graham Greene.

Her first novel, Strangers on a Train, has been adapted for stage and screen numerous times, notably by Alfred Hitchcock in 1951. Her 1955 novel The Talented Mr. Ripley has been adapted numerous times for film, theatre, and radio. Writing under the pseudonym "Claire Morgan," Highsmith published the first lesbian novel with a happy ending, The Price of Salt, republished 38 years later as Carol under her own name and later adapted into a 2015 film.

Many of Highsmith's 22 novels were set in Greenwich Village, where she lived at 48 Grove Street from 1940 to 1942, before moving to 345 E. 57th Street. In 1942, Highsmith graduated from Barnard College, where she studied English composition, playwriting, and short story prose.

After graduating from college, and despite endorsements from "highly placed professionals," she applied without success for a job at publications such as Harper's Bazaar, Vogue, Mademoiselle, Good Housekeeping, Time, Fortune, and The New Yorker.

Based on the recommendation from Truman Capote, Highsmith was accepted by the Yaddo artist's retreat during the summer of 1948, where she worked on her first novel, Strangers on a Train.

Highsmith endured cycles of depression, some of them deep, throughout her life. Despite literary success, she wrote in her diary of January 1970: " am now cynical, fairly rich ... lonely, depressed, and totally pessimistic."

Over the years, Highsmith suffered from female hormone deficiency, anorexia nervosa, Chronic anemia, Buerger's disease, and lung cancer.

According to her biographer Andrew Wilson, Highsmith's personal life was a "troubled one." She was an alcoholic who, allegedly, never had an intimate relationship that lasted for more than a few years, and she was seen by some of her contemporaries and acquaintances as misanthropic and hostile. Her chronic alcoholism intensified as she grew older.

She famously preferred the company of animals to that of people and stated in a 1991 interview, "I choose to live alone because my imagination functions better when I don't have to speak with people."

Otto Penzler, her U.S. publisher through his Penzler Books imprint, had met Highsmith in 1983, and four years later witnessed some of her theatrics intended to create havoc at dinner tables and shipwreck an evening. He said after her death that "[Highsmith] was a mean, cruel, hard, unlovable, unloving human being ... I could never penetrate how any human being could be that relentlessly ugly. ... But her books? Brilliant."

Other friends, publishers, and acquaintances held different views of Highsmith. Editor Gary Fisketjon, who published her later novels through Knopf, said that "She was very rough, very difficult ... But she was also plainspoken, dryly funny, and great fun to be around."

Composer David Diamond met Highsmith in 1943 and described her as being "quite a depressed person—and I think people explain her by pulling out traits like cold and reserved, when in fact it all came from depression."

J. G. Ballard said of Highsmith, "The author of Strangers on a Train and The Talented Mr. Ripley was every bit as deviant and quirky as her mischievous heroes and didn't seem to mind if everyone knew it."

Screenwriter Phyllis Nagy, who adapted The Price of Saltinto the 2015 film Carol, met Highsmith in 1987 and the two remained friends for the rest of Highsmith's life. Nagy said that Highsmith was "very sweet" and "encouraging" to her as a young writer, as well as "wonderfully funny."

She was considered by some as "a lesbian with a misogynist streak."

Highsmith loved cats, and she bred about three hundred snails in her garden at home in Suffolk, England. Highsmith once attended a London cocktail party with a "gigantic handbag" that "contained a head of lettuce and a hundred snails" which she said were her "companions for the evening."

She loved woodworking tools and made several pieces of furniture. Highsmith worked without stopping. In later life, she became stooped, with an osteoporotic hump. Though the 22 novels and 8 books of short stories she wrote were highly acclaimed, especially outside of the United States, Highsmith preferred her personal life to remain private.

A lifelong diarist, Highsmith left behind eight thousand pages of handwritten notebooks and diaries.

As an adult, Patricia Highsmith's sexual relationships were predominantly with women. She occasionally engaged in sex with men without physical desire for them and wrote in her diary: "The male face doesn't attract me, isn't beautiful to me."

An intensely private person, Highsmith was remarkably open and outspoken about her sexuality. She told Meaker: "the only difference between us and heterosexuals is what we do in bed."

Highsmith, aged 74, died on February 4, 1995, from a combination of aplastic anemia and lung cancer at Carita hospital in Locarno, Switzerland, near the village where she had lived since 1982. She was cremated at the cemetery in Bellinzona; a memorial service was conducted in the Chiesa di Tegna in Tegna, Ticino, Switzerland; and her ashes were interred in its columbarium.

She left her estate, worth an estimated $3 million, and the promise of any future royalties to the Yaddo colony, where she spent two months in 1948 writing the draft of Strangers on a Train. Highsmith bequeathed her literary estate to the Swiss Literary Archives at the Swiss National Library in Bern, Switzerland. Her Swiss publisher, Diogenes Verlag, was appointed literary executor of the estate.

Highsmith was a resolute atheist. Although she considered herself a liberal, and in her school years had gotten along with Black students, in later years she became convinced that Blacks were responsible for the welfare crisis in America. She disliked Koreans because "they eat dogs".

Highsmith was an active supporter of Palestinian rights, a stance which, according to Carol screenwriter Phyllis Nagy, "often teetered into outright antisemitism." When she was living in Switzerland in the 1980s, she used nearly 40 aliases when writing to various government bodies and newspapers deploring the state of Israel and the "influence" of the Jews.

Nevertheless, many of the women she became romantically involved with as well as friends she valued were Jewish, such as Arthur Koestler, whom she met in October 1950 and with whom she had an unsuccessful affair designed to hide her homosexuality, believing that Marc Brandel's disclosure that she was homosexual would hurt her professionally. Moreover, Saul Bellow, also Jewish, was a favorite author.

Highsmith described herself as a social democrat.

She believed in American democratic ideals and in "the promise" of U.S. history, but she was also highly critical of the reality of the country's 20th-century culture and foreign policy. Tales of Natural and Unnatural Catastrophes, her 1987 anthology of short stories, was notoriously anti-American, and she often cast her homeland in a deeply unflattering light. Beginning in 1963, she resided exclusively in Europe. She retained her United States citizenship, despite the tax penalties, of which she complained bitterly while living for many years in France and Switzerland.

After graduating from Barnard College, before her short stories started appearing in print, Highsmith wrote for comic book publishers from 1942 and 1948, while she lived in New York City and Mexico. Answering an ad for "reporter/rewrite," she landed a job working for comic book publisher Ned Pines in a "bullpen" with four artists and three other writers. Initially scripting two comic-book stories a day for $55-a-week paychecks, Highsmith soon realized she could make more money by freelance writing for comics, a situation which enabled her to find time to work on her own short stories and live for a period in Mexico. The comic book scriptwriter job was the only long-term job Highsmith ever held.

From 1942–43, for the Sangor-Pines shop (Better/Cinema/Pines/Standard/Nedor), Highsmith wrote "Sergeant Bill King" stories and contributed to Black Terror and Fighting Yank comics; and wrote profiles such as Catherine the Great, Barney Ross, and Capt. Eddie Rickenbacker for the "Real Life Comics" series. From 1943–1946, under editor Vincent Fago at Timely Comics, she contributed to its U.S.A. Comics wartime series, writing scenarios for comics such as Jap Buster Johnson and The Destroyer. During these same years she wrote for Fawcett Publications, scripting for Fawcett Comics characters "Crisco and Jasper" and others. Highsmith also wrote for True Comics, Captain Midnight, and Western Comics

When Highsmith wrote the psychological thriller novel The Talented Mr. Ripley (1955), one of the title character's first victims is a comic-book artist named Reddington: "Tom had a hunch about Reddington. He was a comic-book artist. He probably didn't know whether he was coming or going."

Early novels and short stories

Highsmith's first novel, Strangers on a Train, proved modestly successful upon publication in 1950, and Alfred Hitchcock's 1951 film adaptation of the novel enhanced her reputation.

Highsmith's second novel, The Price of Salt, was published in 1952 under the nom de plume Claire Morgan.

Highsmith mined her personal life for the novel's content. Its groundbreaking happy ending and departure from stereotypical conceptions about lesbians made it stand out in lesbian fiction.

In what BBC 2's "The Late Show" presenter Sarah Dunant described as a "literary coming out" after 38 years of disaffirmation, Highsmith finally acknowledged authorship of the novel publicly when she agreed to the 1990 publication by Bloomsbury retitled Carol. Highsmith wrote in the "Afterword" to the new edition:

If I were to write a novel about a lesbian relationship, would I then be labelled a lesbian-book writer? That was a possibility, even though I might never be inspired to write another such book in my life. So I decided to offer the book under another name.

The appeal of The Price of Salt was that it had a happy ending for its two main characters, or at least they were going to try to have a future together. Prior to this book, homosexuals male and female in American novels had had to pay for their deviation by cutting their wrists, drowning themselves in a swimming pool, or by switching to heterosexuality (so it was stated), or by collapsing – alone and miserable and shunned – into a depression equal to hell.

How was it possible to be afraid and in love, Therese thought. The two things did not go together. How was it possible to be afraid, when the two of them grew stronger together every day? And every night. Every night was different, and every morning. Together they possessed a miracle.

–The Price of Salt, chapter eighteen (Coward-McCann, 1952)

The paperback version of the novel sold nearly one million copies before its 1990 reissue as Carol.[80] The Price of Saltis distinct for also being the only one of Highsmith's novels in which no violent crime takes place,[47] and where her characters have "more explicit sexual existences" and allowed "to find happiness in their relationship."

Her short stories appeared for the first time in Ellery Queen's Mystery Magazine in the early 1950s.

Her last novel, Small g: a Summer Idyll, was rejected by Knopf (her usual publisher by then) several months before her death,[81] leaving Highsmith without an American publisher. It was published posthumously in the United Kingdom by Bloomsbury Publishing in March 1995, and nine years later in the United States by W.W. Norton

In 1955, Highsmith wrote The Talented Mr. Ripley, a novel about Tom Ripley, a charming criminal who murders a rich man and steals his identity. Highsmith wrote four sequels: Ripley Under Ground (1970), Ripley's Game (1974), The Boy Who Followed Ripley (1980) and Ripley Under Water (1991), about Ripley's exploits as a con artist and serial killer who always gets away with his crimes. The series—collectively dubbed "The Ripliad"—are some of Highsmith's most popular works and have sold millions of copies worldwide.

The "suave, agreeable and utterly amoral" Ripley is Highsmith's most famous character, and has been critically acclaimed for being "both a likable character and a cold-blooded killer."He has typically been regarded as "cultivated," a "dapper sociopath," and an "agreeable and urbane psychopath."

Sam Jordison of The Guardian wrote, "It is near impossible, I would say, not to root for Tom Ripley. Not to like him. Not, on some level, to want him to win. Patricia Highsmith does a fine job of ensuring he wheedles his way into our sympathies."

Film critic Roger Ebert made a similar appraisal of the character in his review of Purple Noon, Rene Clement's 1960 film adaptation of The Talented Mr. Ripley: "Ripley is a criminal of intelligence and cunning who gets away with murder. He's charming and literate, and a monster. It's insidious, the way Highsmith seduces us into identifying with him and sharing his selfishness; Ripley believes that getting his own way is worth whatever price anyone else might have to pay. We all have a little of that in us."

Novelist Sarah Waters esteemed The Talented Mr. Ripley as the "one book I wish I'd written."

The first three books of the "Ripley" series have been adapted into films five times. In 2015, The Hollywood Reporter announced that a group of production companies were planning a television series based on the novels. The series is currently in development.

Honors

1979 : Grand Master, Swedish Crime Writers' Academy

1987 : Prix littéraire Lucien Barrière [fr], Festival du Cinéma Américain de Deauville

1989 : Chevalier dans l'Ordre des Arts et des Lettres, French Ministry of Culture

1991 : Candidate, Nobel Prize in Literature

1993 : Best Foreign Literary Award, Finnish Crime Society

2008 : Greatest Crime Writer, The Times

Awards and nominations

1946 : O. Henry Award, Best First Story, for The Heroine (in Harper's Bazaar)

1951 : Nominee, Edgar Allan Poe Award, Best First Novel, Mystery Writers of America, for Strangers on a Train

1956 : Edgar Allan Poe Scroll (special award), Mystery Writers of America, for The Talented Mr. Ripley

1957 : Grand Prix de Littérature Policière, International, for The Talented Mr. Ripley

1963 : Nominee, Edgar Allan Poe Award, Best Short Story, Mystery Writers of America, for The Terrapin (in Ellery Queen's Mystery Magazine)

1963 : Special Award, Mystery Writers of America, for The Terrapin

1964 : Silver Dagger Award, Best Foreign Novel, Crime Writers' Association, for The Two Faces of January (pub. Heinemann)

1975 : Prix de l'Humour noir Xavier Forneret [fr] for L'Amateur d'escargots (pub. Calmann-Lévy) (English title: Eleven)

Bibliography

Novels

Strangers on a Train (1950)

The Price of Salt (1952) (as Claire Morgan) (republished as Carol in 1990 under Highsmith's name)

The Blunderer (1954)

Deep Water (1957)

A Game for the Living (1958)

This Sweet Sickness (1960)

The Cry of the Owl (1962)

The Two Faces of January (1964)

The Glass Cell (1964)

A Suspension of Mercy (1965) (published as The Story-Teller in the U.S.)

Those Who Walk Away (1967)

The Tremor of Forgery (1969)

A Dog's Ransom (1972)

Edith's Diary (1977)

People Who Knock on the Door (1983)

Found in the Street (1986)

Small g: a Summer Idyll (1995)

The "Ripliad"Edit

The Talented Mr. Ripley (1955)

Ripley Under Ground (1970)

Ripley's Game (1974)

The Boy Who Followed Ripley (1980)

Ripley Under Water (1991)

Short story collections

Eleven (1970) (Foreword by Graham Greene) (published as The Snail-Watcher and Other Stories in the U.S.)

Little Tales of Misogyny (1975) (published first as Kleine Geschichtgen für Weiberfeinde in Switzerland)

The Animal Lover's Book of Beastly Murder (1975)

Slowly, Slowly in the Wind (1979)

The Black House (1981)

Mermaids on the Golf Course (1985)

Tales of Natural and Unnatural Catastrophes (1987)

Chillers (1990)

Nothing That Meets the Eye: The Uncollected Stories (2002) (published posthumously)

Other books

Miranda the Panda is on the Veranda (1958) with Doris Sanders (children's book of verse and illustrations)

Plotting and Writing Suspense Fiction (1966) (enlarged and revised edition, 1981)

Essays and articles

"Not-Thinking with the Dishes" (1982), Whodunit? A Guide to Crime, Suspense and Spy Fiction, pg. 92. By H. R. F. Keating, Windward, ISBN 0-7112-0249-4[96]

"Scene of the Crime" (1989), Granta, Issue No. 29, Winter

Miscellaneous

"Introduction" (1977), The World of Raymond Chandler. Ed. Miriam Gross, Weidenfeld and Nicolson, ISBN 0-297-77362-3[97]

"Foreword" (1987), Crime and Mystery: The 100 Best Books. By H. R. F. Keating, Xanadu, ISBN 0-947761-25-X [98]

Collected works

Mystery Cats III: More Feline Felonies (1995) (Signet Books, ISBN 978-0451182937) (anthology includes Patricia Highsmith)

The Selected Stories of Patricia Highsmith (2001) (W. W. Norton & Company, ISBN 0-393-02031-2)

Patricia Highsmith: Selected Novels and Short Stories (2011) (W. W. Norton & Company, ISBN 978-0-393-08013-1)

Film, television, theatre and radio adaptations

Several of Highsmith's works have been adapted for other media, some more than once. In 1978, Highsmith was president of the jury at the 28th Berlin International Film Festival.

1951. Strangers on a Train was adapted as a film of same name directed by Alfred Hitchcock starring Farley Granger as Guy Haines, Robert Walker as Anthony Bruno, Ruth Roman as Anne Morton, Patricia Hitchcock as Barbara Morton and Laura Elliott as Miriam Joyce Haines.

1963. The Blunderer was adapted as French-language film Le meurtrier ("The Murderer"), directed by Claude Autant-Lara starring Maurice Ronet as Walter Saccard, Yvonne Furneaux as Clara Saccard, Gert Fröbe as Melchior Kimmel, Marina Vlady as Ellie and Robert Hossein as Corbi. It is known in English as Enough Rope.

1977. This Sweet Sickness was adapted as French-language film Dites-lui que je l'aime, directed by Claude Miller starring Gérard Depardieu as David Martineau, Miou-Miou as Juliette, Dominique Laffin as Lise, and Jacques Denis as Gérard Dutilleux. It is known in English as This Sweet Sickness.

1978. The Glass Cell was adapted as German-language film Die gläserne Zelle, directed by Hans W. Geißendörfer starring Brigitte Fossey as Lisa Braun, Helmut Griem as Phillip Braun, Dieter Laser as David Reinelt and Walter Kohut as Robert Lasky.

1981. Deep Water was adapted as French-language film Eaux profondes, directed by Michel Deville starring Isabelle Huppert as Melanie and Jean-Louis Trintignant as Vic Allen.

1983. Edith's Diary was adapted as German-language film Ediths Tagebuch, directed by Hans W. Geißendörfer starring Angela Winkleras Edith.

1986. The Two Faces of January was adapted as German-language film Die zwei Gesichter des Januars, directed by Wolfgang Storch starring Charles Brauer as Chester McFarland, Yolanda Jilot as Colette McFarland and Thomas Schücke as Rydal Keener.

1987. The Cry of the Owl was adapted as French-language film Le cri du hibou, directed by Claude Chabrol starring Christophe Malavoyas Robert, Mathilda May as Juliette, Jacques Penot as Patrick and Virginie Thévenet as Véronique.

1987. The film version of Strangers on a Train by Alfred Hitchcock inspired the black comedy American film Throw Momma from the Train, directed by Danny DeVito.

1989. The Story Teller was adapted as German-language film Der Geschichtenerzähler, directed by Rainer Boldt starring Udo Schenk as Nico Thomkins and Anke Sevenich as Helen Thomkins.

2009. The Cry of the Owl was adapted as a film of same name, directed by Jamie Thraves starring Paddy Considine as Robert Forester and Julia Stiles as Jenny Thierolf.

2014. The Two Faces of January was adapted as a film of same name, written and directed by Hossein Amini starring Viggo Mortensenas Chester MacFarland, Kirsten Dunst as Colette MacFarland and Oscar Isaac as Rydal. It was released during the 64th Berlin International Film Festival.

2014. A Mighty Nice Man was adapted as a short film, directed by Jonathan Dee starring Kylie McVey as Charlotte, Jacqueline Baum as Emilie, Kristen Connolly as Charlotte's Mother, and Billy Magnussen as Robbie.

2015. A film adaption of The Price of Salt, titled Carol, was written by Phyllis Nagy and directed by Todd Haynes, starring Cate Blanchettas Carol Aird and Rooney Mara as Therese Belivet.

2016. The Blunderer was adapted as A Kind of Murder, directed by Andy Goddard starring Patrick Wilson as Walter Stackhouse, Jessica Biel as Clara Stackhouse, Eddie Marsan as Marty Kimmel and Haley Bennett as Ellie Briess.

"Ripliad"Edit

1960: The Talented Mr. Ripley was adapted as French-language film Plein soleil (titled Purple Noon for English-language audiences, though it translates as "Full Sun"). Directed by René Clément starring Alain Delon as Tom Ripley, Maurice Ronet as Philippe Greenleaf, and Marie Laforêt as Marge Duval. Both Highsmith and film critic Roger Ebert criticized the screenplay for altering the ending to prevent Ripley from going unpunished as he does in the novel.[103][87]

1977: Ripley's Game (third novel) and a "plot fragment" of Ripley Under Ground (second novel) were adapted as German-language film Der Amerikanische Freund (The American Friend). Directed by Wim Wenders with Dennis Hopper as Ripley. Highsmith initially disliked the film but later found it stylish, although she did not like how Ripley was interpreted.

1999: The Talented Mr. Ripley was adapted as an American production. Directed by Anthony Minghella with Matt Damon as Ripley, Jude Law as Dickie Greenleaf, and Gwyneth Paltrow as Marge Sherwood.

2002: Ripley's Game was adapted as a film of same name for an English-language Italian production. Directed by Liliana Cavani with John Malkovich as Ripley, Chiara Caselli as Luisa Harari Ripley, Ray Winstone as Reeves Minot, Dougray Scott as Jonathan Trevanny, and Lena Headey as Sarah Trevanny. Although not all reviews were favorable, Roger Ebert regarded it as the best of all the Ripley films.[105]

2005: Ripley Under Ground was adapted as a film of same name. Directed by Roger Spottiswoode with Barry Pepper as Ripley, Jacinda Barrett as Héloïse Plisson-Ripley, Willem Dafoe as Neil Murchison, and Tom Wilkinson as John Webster.

Television

1958. Strangers on a Train was adapted by Warner Brothers for an episode of the TV series 77 Sunset Strip.

1982. Scenes from the Ripley novels were dramatized in the episode A Gift for Murder of The South Bank Show, with Jonathan Kentportraying Tom Ripley. The episode included an interview with Patricia Highsmith.[106]

1983. Deep Water was adapted as a miniseries for German television as Tiefe Wasser, directed by Franz Peter Wirth starring Peter Bongartz as Vic van Allen, Constanze Engelbrecht as Melinda van Allen, Reinhard Glemnitz as Dirk Weisberg, Raimund Harmstorf as Anton Kameter, and Sky du Mont as Charley de Lisle.[107][108]

1987. The Cry of the Owl was adapted for German television as Der Schrei der Eule, directed by Tom Toelle starring Matthias Habich as Robert Forster, Birgit Doll as Johanna Tierolf, Jacques Breuer as Karl Weick, Fritz Lichtenhahn as Inspektor Lippenholtz, and Doris Kunstmann as Vicky.

1990. The twelve episodes of the television series Mistress of Suspense are based on stories by Highsmith. The series aired first in France, then in the UK. It became available in the U.S. under the title Chillers.[citation needed]

1993. The Tremor of Forgery was adapted as German television film Trip nach Tunis, directed by Peter Goedel starring David Hunt as Howard Ingham, Karen Sillas as Ina Pallant and John Seitz as Francis J. Adams.

1995. Little Tales of Misogyny was adapted as Spanish/Catalan television film Petits contes misògins, directed by Pere Sagristà starring Marta Pérez, Carme Pla, Mamen Duch, and Míriam Iscla.

1996. Strangers on a Train was adapted for television as Once You Meet a Stranger, directed by Tommy Lee Wallace starring Jacqueline Bisset as Sheila Gaines ("Guy"), Theresa Russell as Margo Anthony ("Bruno") and Celeste Holm as Clara. The gender of the two lead characters was changed from male to female.

1996. A Dog's Ransom was adapted as French television film La rançon du chien, directed by Peter Kassovitz starring François Négret as César, François Perrot as Edouard Raynaud, Daniel Prévost as Max Ducasse and Charlotte Valandrey as Sophie.

Theatre

1998. The Talented Mr. Ripley was adapted for the stage as a play of same name by playwright Phyllis Nagy.[109] It was revived in 2010.[110]

2013. Strangers on a Train was adapted as a play of same name by playwright Craig Warner.

Radio

2002. A four-episode radio drama of The Cry of the Owl was broadcast by BBC Radio 4, with voice acting by John Sharian as Robert Forester, Joanne McQuinn as Jenny Theirolf, Adrian Lester as Greg Wyncoop, and Matt Rippy as Jack Neilsen.

2009. All five books of the "Ripliad" were dramatized by BBC Radio 4, with Ian Hart voicing Tom Ripley.

2014. A five-segment dramatization of Carol (aka The Price of Salt) was broadcast by BBC Radio 4, with voice acting by Miranda Richardson as Carol Aird and Andrea Deck as Therese Belivet.