One of the finest short stories in the English language, 'Babylon Revisited’, written by F Scott Fitzgerald after the Great Crash, is an intensely personal portrait of a man who has squandered his life. It’s also a perfect tale for the times we live in .

One of the finest short stories in the English language, 'Babylon

Revisited’, written by F Scott Fitzgerald after the Great Crash, is an

intensely personal portrait of a man who has squandered his life. It’s also a

perfect tale for the times we live in .

Today, Francis Scott Key

Fitzgerald may be one of America’s most celebrated novelists, but during his

lifetime, he was best known as a writer of short stories. At the end of the

Twenties, he was the highest-paid writer in America earning fees of $4,000 per

story (about $50,000 today) and published in mainstream magazines such as The

Saturday Evening Post. Over 20 years, he wrote almost 200 stories in addition

to his four novels, publishing 164 of them in magazines.

When Ernest Hemingway first met Fitzgerald, in Paris in 1925, it

was within weeks of the publication of The Great Gatsby; Hemingway later wrote

that before reading Gatsby, he thought that Fitzgerald “wrote Saturday Evening

Post stories that had been readable three years before, but I never thought of

him as a serious writer”.

Gatsby would change all that, of course, so thoroughly that now we

may be in danger of forgetting Fitzgerald’s stories. The haste in which he

wrote them, in order to pay for the luxurious lifestyle he enjoyed with his

wife, Zelda, means that the stories are uneven in quality, but at their best

they are among the finest stories in English. And “Babylon Revisited”, a

Saturday Evening Post story first published exactly 80 years ago next month –

and free inside next Saturday’s edition of the Telegraph – is probably the

greatest. A tale of boom and bust, about the debts one has to pay when the

party comes to an end, it is a story with particular relevance for the way we

live now.

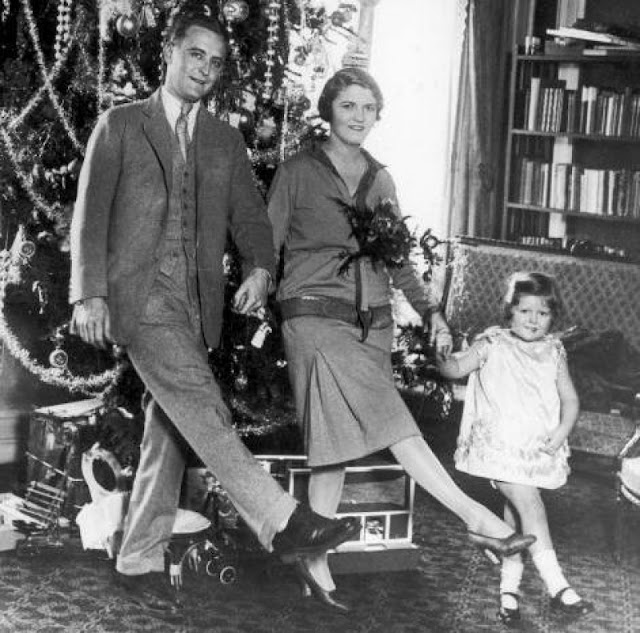

Fitzgerald’s fortunes uncannily mirrored the fortunes of the

nation he wrote about: his first novel, This Side of Paradise, became a runaway

bestseller in early 1921, just as America entered the boom period that

Fitzgerald himself would name the Jazz Age. He and Zelda became celebrities and

began living the high life. They were the golden couple of the Twenties,

“beautiful and damned”, as the prophetic title of Fitzgerald’s 1922 novel

suggested, treated like royalty in America’s burgeoning celebrity culture.

Glamorous, reckless and profligate, the Fitzgerald’s were spendthrift in every

sense. Much later, Fitzgerald would have to take account of all they had

squandered – not only wealth, but beauty, youth, health, and even his genius.

In early 1924, the Fitzgerald’s sailed from New York with their

three-year-old daughter, Scottie, for Europe, where they joined the growing

crowd of American expatriates enjoying the comparatively cheap cost of living

in post First World War Paris and the Riviera. There they became friends with

Hemingway, as well as with other writers and artists of the day. Fitzgerald’s

biographers record that while in Paris, Fitzgerald’s routine was to rise at

11am, and begin work at 5pm. He claimed to write most days until 3am, but the

reality was that usually he and Zelda could be found among the cabarets and

clubs of Montmartre and the Left Bank, where they drank, danced, flirted and

fought into the small hours

When the Great Crash came at the end of 1929, the Fitzgerald’s

crashed also, just as they had roared along with the Roaring Twenties. In April

1930, Zelda had a nervous breakdown and was eventually diagnosed with

schizophrenia; she would spend the rest of her life in and out of psychiatric

hospitals.

And in the early Thirties, as America sank into Depression,

Fitzgerald found himself battling depression. His alcoholism was spiraling out

of control, his stories were now abruptly out of key with the mood of the

nation, and he found it increasingly difficult to earn enough to pay for

Zelda’s medical care and their daughter’s education.

Written in December 1930, just eight months after Zelda’s

breakdown, the elegiac “Babylon Revisited” is Fitzgerald’s exquisitely painful

meditation on what he had wasted, his recognition that the cost of living it

large is not just financial but emotional, psychological and spiritual – and that

one can’t live in arrears forever.

That Christmas, Fitzgerald brought Scottie to visit her mother in

a Swiss sanatorium, but Zelda’s erratic behavior frightened the nine-year-old

girl; Scott took his daughter skiing for the rest of her school holiday.

“Babylon Revisited”, written just as Fitzgerald faced the prospect

that Zelda might be lost to him for good, and in fear for his ability to care

for his daughter, is itself a kind of reckoning of the price one has to pay.

Financial debts, paying the price for past extravagance, becomes a metaphor for

moral debts, the loss of one’s sense of character or one’s personal credit with

the world.

The tale of a man who has lost everything but is fighting to

redeem himself, “Babylon Revisited” concerns Charlie Wales, an American

expatriate who lives a profligate life in Paris during the Twenties. One night

during a bacchanalian spree, he quarrels with his wife, Helen, and she

retaliates by kissing another man. Charlie storms home alone and Helen arrives

home an hour later, too drunk and disoriented to find a taxi. She dies soon

after; Charlie has a breakdown and is institutionalized before losing all his

money in the crash.

Their daughter, Honoria, goes to live with Helen’s sister Marion.

As the story opens three years later, Charlie has returned to Paris sober,

financially successful again and determined to pull his life together. He has

come to reclaim his symbolically named daughter: if honor is restored to him

perhaps he can salvage something from the wreckage of his life.

“Babylon Revisited” clearly chimes with Fitzgerald’s own life in

late 1930: the extravagant dissipation of life in Paris during the boom years;

the wife lost to illness; a fortune frittered away in the confidence that “even

when you were broke, you didn’t worry about money,” as Fitzgerald later wrote

about the rampant spending in the Twenties, “because it was in such profusion

around you.” And it is a story about a father’s recognition that, especially in

the absence of her mother, his daughter needs him to face up to his

responsibilities.

Fitzgerald carefully patterns the story so that it comes full

circle, and Charlie ends where he began, in the Paris Ritz Bar. The setting is

emblematically appropriate, suggesting Charlie’s twin crimes: his careless

squandering of wealth and his drinking. But beginning and ending in the same

location also hints at one of the story’s deeper themes: Charlie will end up

where he began, borne back ceaselessly into the past, as Fitzgerald wrote at

the end of The Great Gatsby. For Charlie Wales revisiting Babylon does not

bring closure; coming full circle merely creates a spiraling sense of loss.

Throughout “Babylon Revisited”, Fitzgerald uses economic metaphors

to underscore the idea that debts must be paid. The story reverberates with

uncanny echoes – or rather, anticipations – of our own era, the way in which we

trusted that living on credit could last forever. What Fitzgerald shows us is

the effects that this mistake has not only on our economy, but on our characters:

that money is the least of what we have to lose.

The poignancy of the story derives from its sense of injustice: a

recovering alcoholic is trying to prove that he’s reformed and if we feel from

the outset of the story a sense of impending doom, we might predict that

Charlie will fall off the wagon. But Fitzgerald twists the knife by making

Charlie’s reformation authentic: he has accepted his responsibilities by coming

back to face the past, own up to his mistakes and remedy them by repairing what’s

left of his family. But that may not be enough.

At one point during his stay in Paris, Charlie revisits his old

haunts on the Left Bank and understands at last: “I spoiled this city for

myself. I didn’t realize it, but the days came along one after another, and

then two years were gone, and everything was gone, and I was gone.” He has got

himself back but the question the story poses is whether everything is gone for

good.

Wandering through Montmartre, Charlie suddenly realizes the extent

of his wastefulness in what is perhaps the most superb passage in this tale:

“All the catering to vice and waste was on an utterly childish scale, and he

suddenly realized the meaning of the word 'dissipate’ – to dissipate into thin

air; to make nothing out of something. In the little hours of the night every

move from place to place was an enormous human jump, an increase of paying for

the privilege of slower and slower motion. He remembered thousand-franc notes

given to an orchestra for playing a single number, hundred-franc notes tossed

to a doorman for calling a cab. But it hadn’t been given for nothing. It had

been given, even the most wildly squandered sum, as an offering to destiny that

he might not remember the things most worth remembering, the things that now he

would always remember – his child taken from his control, his wife escaped to a

grave in Vermont.”

The idea of “dissipation” as an active loss is perhaps the story’s

central insight, and it is one to which Fitzgerald would return again and again

in his fiction of the Thirties. The passage evokes the sense of vanished and

wasted time, the remorse that characterizes the morning after the night before,

the sense of everything being spent.

“Babylon Revisited” is at once timeless and startlingly modern in

its evocation of a single father struggling with alcoholism and trying to care

for his daughter and coming to terms with the costs of extravagance. Part of

the tale’s poignancy is Fitzgerald’s recognition that the tragedy is not just

Charlie’s: it is also his daughter’s. When Charlie comes to ask Marion to

return Honoria to him, he realizes Marion is bitter, particularly because of

Charlie’s easy acquisition of wealth.

Marion says she is “delighted” that Americans have deserted Paris

following the crash: “Now at least you can go into a store without their

assuming you’re a millionaire.” Charlie’s response is revealing: “But it was

nice while it lasted… We were a sort of royalty, almost infallible, with a sort

of magic around us.” Only it didn’t last long: they wasted their “sort of

magic” in search of a life that could never be as magnificent as their hopes,

just as surely as Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald did.

Nine years after the publication of “Babylon Revisited”, less than

a year before he would die at 44, Fitzgerald wrote his daughter Scottie a

letter about the story: “You have earned some money for me this week because I

sold 'Babylon Revisited,’ in which you are a character, to the pictures (the

sum received wasn’t worthy of the magnificent story – neither of you nor of me

– however, I am accepting it).”

Like Charlie, Fitzgerald learnt

the hard way that loss is remorseless, absolute; what has been wasted is

irrecoverable. But as “Babylon Revisited” also shows, even out of the wreckage

some things can be salvaged, if not everything: what Fitzgerald retrieved he

bequeathed to us, the hard-won lessons of his life transformed into

heartbreaking art.