Ye who, passing graves by

night,

Glance not to the left nor

right,

Lest a spirit should

arise,

Cold and white, to freeze

your eyes...

James Russell Lowell, "The

Ghost-Seer"

The ghost of Philip Barton Key II

was the son of Francis Scott Key and the nephew of Chief Justice Roger B.

Taney, is said to haunt Lafayette Square and can be seen on dark nights near

the spot where he was shot.

In the spring of 1858, Key, who

was the United States Attorney for the District of Columbia, began having an

affair with Teresa Bagioli Sickles, the wife of his friend Daniel Sickles.

Teresa Bagioli Sickles

(Born in New York City as Teresa Da Ponte Bagioli) was the daughter of the

wealthy and famous Italian singing teacher Antonio Bagioli. Her mother, Maria

was the adopted (But alleged natural) child of Lorenzo Da Ponte, a noted music

teacher, who had worked as Mozart's librettist on such masterpieces as The Marriage of Figaro.

Maria’s half- brother, a New York

University professor, was a teenage friend of Dan Sickles, (Below) the son of Manhattan patent

lawyer and politician who had learned the printer's trade but wanted more for

his career.

The Da Ponte family helped Sickles secure a

scholarship to New York University. They

also allowed him to move into their home and knew Teresa, his future wife, in

her infancy. Sickles, who at age 20 had already been indicted for fraud, was

admitted to the bar in 1846 and was elected to the New York State Assembly in

1847 as a Tammany Hall hack.

Fanny White (Born Jane Augusta

Blankman in 1823) was a successful New York Prostitute, Madam, brothel owner,

and courtesan. She was noted on two

contents for her wit, her charm, and her beauty, and her ability to coral

powerful and wealthy men. White became Sickles kept woman and kept her in money

and jewels. He probably arranged the mortgage on Fanny’s brothel, under the

name of his friend Antonio Bagioli and Fanny contributed a portion of the brothel

earnings to Sickles’ election campaign.

When he was elected to the New York State Assembly later that year, he

had the bad sense to take her up to Albany and introduced her to his fellow

legislators and gave her a tour of the Assembly Chamber.

Most of the legislators knew who

Fanny was and were outraged at Sickles indiscretion and was censured by members

of the Whig party. On that same trip,

when the couple went out of the town for the evening Fanny dressed as a man,

which was illegal at the time, and was subsequently arrested and placed in jail

for the night.

In September 1852, when Sickles

married sixteen-year old Teresa Bagioli, Fanny was so upset that she followed

Sickles to his hotel and beat him with a riding crop. But they made up and in

August of 1853, Fanny travelled with Sickles to England, leaving his pregnant

wife at home.

Sickles arranged Fanny’s passport, when

Sickles was acting as secretary to James Buchanan, the U. S. Minister to the

Court of St. James. Once in London,

Sickles and Fanny cavorted openly, attending theaters, operas, and diplomatic

events, arm in arm.

Remarkably, Fanny was even

introduced to Queen Victoria at a reception at Buckingham Palace, as “Miss

Bennett of New York.”, the name being a slap at the hot-tempered Scot, James

Gordon Bennett, founder, editor, and publisher of the New York Herald, whom

Sickles despised. From that point on,

Fanny used the last name, Bennett.

James Gordon Bennett

When James Gordon Bennett learned that Fanny

had used his name in the royal court and was now using it as her business name

as well, Bennett was furious and would eventually get his revenge in his

newspapers, which, at the time, had the highest circulation in America.

Fanny left London in the spring

of 1854 when Teresa Bagioli Sickles arrived in the city to join her husband.

Fanny reportedly toured the continent and was said to have been tossed out of

the Paris Opera by the police after causing a drunken scene. She eventually

returned to New York and open more brothels.

In 1859, she met and married

noted criminal defense lawyer Edmond Blankman, seven years her junior. Fanny

died suddenly on October 12, 1860, at age 37. A rumor swept the city that she

had been poisoned by her husband who wanted her fortune (Estimated to be in the

range of two to four million dollars, mostly in real estate) for his own.

The City Coroner performed an

autopsy and although he found signs of exposure to tuberculosis, syphilis,

symptoms of cardiovascular disease, and extensive bleeding in the brain, no

poison was found.

In 1851, Assemblyman Sickles, now thirty-three

years old, met the fifteen-year-old Teresa again and, according to him anyway,

fell instantly in love with her and proposed marriage.

Although her parents

understandably refused to consent to the marriage, the couple wed anyway, in

1852, in a civil ceremony. Seven months

Teresa gave birth to their child, Laura Buchanan Sickles. (Sickles later had a falling out with his

daughter and they never spoke afterwards.

She died before her father did, of alcoholism in 1891)

In 1855, Sickles was elected to the New York

Senate and served until 1857 when he won a seat in the United States House of

Representatives. The couple were deeply involved in Washington society and

hosted popular formal dinners every Thursday evening at their rented home on

Madison Place. Teresa befriended the difficult Mary Todd Lincoln and was said

to have attended séances held by Mary Todd.

Sickles continued to his love

affairs with other women in both New York and Washington (at a leased room in a

Baltimore hotel) and badly neglected his wife and child. In the meantime, in the spring of 1858,

Teresa started an affair with Georgetowner Phillip Barton Key who said to

follow Teresa at social gatherings and was often seen leaving her home while

her husband was away. The charming and flirtatious Key, said to be the most handsome man in Washington, was a widower and a father to four children.

Key

The affair between Teresa and Key

was widely known in Washington’s gossipy social circles and on February 26,

1859, someone sent Dan Sickles a letter telling him about his wife’s affair

with young Mister Keyes. Sickles showed the note to a friend, George

Wooldridge, and then “put his hands to his head and sobbed in the lobby of the

House of Representatives” although the accuracy of that event is highly

doubtful.

Teresa in later years

Sickles probably knew what was

happening. Friends of Sickles had warned him about Keys reputation as a lady’s

man and in March of 1858, Sickles confronted Keys over the allegations that he

was carrying on an affair with Sickles wife.

But keys was a silver-tongued lawyer and Sickles walked away from the

meeting absolutely sure that Keys could be trusted around his wife. Sickles

looked into the matter and found evidence that the claims were true. He learned

that the pair often slipped away to a vacant house on 15th Street, then a poor

area, that Key rented.

Sickles confronted Teresa on

Saturday night, February 26th, in her bedroom (They had separate sleeping

arraignments, on different floors) with the facts, she broke down and admitted

to the affair and wrote a confession, by force, saying as much.

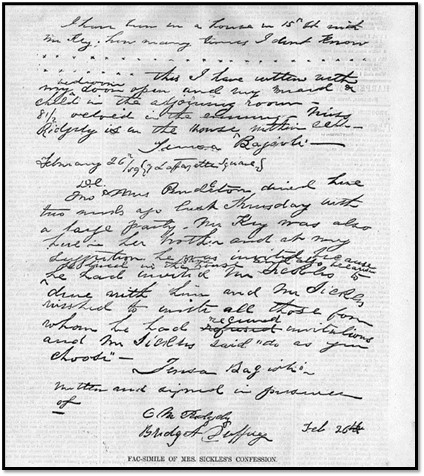

Teresa's handwritten confession

The letter was later reprinted on the front page of Harper’s Weekly, a national yellow sheet newspaper. In part, the letter read, “I did not think it safe to meet (Phillip) in this house, because there are servants who might suspect something….He then told me he had hired (a) house as a place where he and I could meet. I agreed to it. There was a bed in the second story…. The room is warmed by a wood fire. Mr. Key generally goes first… I went there alone. I did what is usual for a wicked woman to do”.

A coachman later testified that

Key and Teresa would take carriage rides to various cemeteries, where,

according to him, “They would walk down the grounds out of my sight, and be

away an hour or an hour-and-a-half.”

The next day, in the afternoon,

Samuel Butterworth, a friend of Sickles who had arrived to Sickles house to

comfort him, spotted Key in Lafayette Square sitting on a bench outside the

Sickles home, allegedly signaling to Teresa with a handkerchief. Sickles sent a friend outside to delay Key

while Sickles armed himself with several pistols, a revolver and two

derringers, placed on an overcoat and left the house, and confronted Key at the

corner of Madison Place N.W. and Pennsylvania Avenue, across the street from

the White House.

Sickles yelled “Key, you scoundrel, you have

dishonored my home; you must die.” Pulled out a derringer and shot at the

unarmed Key’s groin but missed. (Other accounts say he reached his hand to his

breast for his weapon). Keys and Sickles

struggled for a few moments while a dozen witnesses watched. Key broke loose

and ran across the street, pitching a pair of opera glasses at Sickles and then

hid behind a tree.

Sickles slowly walked across the

street, pulled out a second derringer and shot Key in the thigh forcing him to

drop to the sidewalk and beg, “Don’t shoot me”, and shouting, “Murder.”

Sickles then pulled out his revolver and

fired, hitting the tree. He walked up to

Key, who was laying prone on the ground, and standing over him fired a shot

point blank into his chest. A fifth shot

misfired and bystanders wrestled the gun away from him before he could deliver the

‘coup de grace’ bullet. Key died moments

later after being carried into the nearby Benjamin Ogle Tayloe House. Key is

buried in Oak Hill Cemetery in Washington.

“He deserved it” Sickles said when he was told Key was dead.

Of course, there was no need to shoot Key to get justice. Key and Teresa had committed what the courts then called criminal intercourse, adultery, a crime in the 19th century. Sickles could have had Keys arrested and jailed, especially in light of the evidence he held. Sickles walked to the home of Attorney General Jeremiah Black, a few blocks away on Franklin Square, and confessed to the murder and surrendered his weapons.

He was taken to jail, but as a

Tammany Hall politician in Washington, life as a prisoner wasn’t altogether

terrible. Sickles was allowed to see as many visitors as he wished, and he saw

dozens of them and was allowed to use the head jailors apartment as a receiving room. He was also

allowed to carry a weapon inside the jail. He also kept Teresa’s wedding ring

in his cell, having taken it from her after he killed Key.

A rather dramatic view of Sickles in jail.

The government half-heartedly indicted Sickles for murder. Sickles hired a dream team of lawyers, most of them leading politicians including Edwin M. Stanton, (later Secretary of War) and James T. Brady, another Tammany Hall upstart.

Sickles plea was historic. He pled insanity in the first use of a

temporary insanity defense in the United States. His argument was that he had

been driven insane by his wife's infidelity and was out of his mind when he

shot Key.

The graphic written confession that Teresa had written, probably under force, proved to be a pivotal bit of information. When the court ruled it as inadmissible, Sickles legal team leaked the letter to the press who reprinted it in full on an almost daily basis.

Although the jury was told, in

detail, that Key was a philanderer and adulterer who sometimes engaged

prostitutes and often drank too much, it was never told the truth about Sickles

personnel life which was much worse than Key’s.

At the same time, Stanton characterized Teresa, as being unable to give

consent to the adultery, in other words, she was raped by Keys.

In the end, in one of the most controversial

trials of the 19th century, twenty days long, in less than an hour the jury

found acquitted Sickles on the basis of temporary insanity, a crime of passion.

The newspapers, which set the tone for public

opinion at the time, welcomed the acquittal and declared Sickles a hero who

saved the dignity of the ladies of Washington from near-rapist Key. Then Sickles publicly forgave Teresa and when

he did the American public turned on him.

The common opinion was, that if he was upset enough to murder a man over

the affair, why forgive her? Where was

his anger towards her?

Teresa died of tuberculosis on

February 5, 1867, at the age of thirty-one. She is buried in an unmarked grave

in the Sickles family plot in Green-Wood Cemetery in New York.

The outbreak of the civil war may

have ripped apart the nation but it saved the politically connected Sickles who

raised a brigade of New York regiments, the Excelsior Brigade. Using his Washington connections, Sickles

managed to have himself appointed to the rank of Major General.

By in large, he was a competent

commander, especially in light of the fact that he had no military training.

However, on July 2, 1863 during the Battle of Gettysburg, Sickles was given

command of the Union Army’s Third Corps. Against orders, he redeployed the

Corps to the west of the Union lines on Cemetery Ridge.

In the brief but vicious battle

that followed, most of the Third Corps was killed or wounded and Sickles

himself was hit in the leg with a cannonball. The lower leg was amputated (it

is now in the National Museum of Health. For years, Sickles visited the leg on the

anniversary of the amputation.)

At the close of the war, he served as U.S. Minister to Spain from 1869 to 1874, after the Senate failed to confirm Henry Shelton Sanford (Shelton wanted to be ambassador to Spain but didn’t want to move to Spain)

In Spain, Sickles was less than

competent at diplomacy but he was rumored to have had an affair with the

deposed Queen Isabella II and in 1871 he married Carmina Creagh, the daughter

of Chevalier de Creagh of Madrid, a Spanish Councilor of State.

Creagh, a Maid of Honor to Queen Isabella of

Spain was introduced to U.S. Minister to Spain, Daniel E. Sickles at a Court

function given by the Queen in 1871. They married soon thereafter and gave all

appearances of a happy relationship, until Sickles resigned his position in

1874 and returned to the U.S. Mrs. Sickles declined to travel with him, and

remained in Spain.

Despite one brief time when she

did live in the United States, and despite having two children, George Stanton

and Edna, Mr. and Mrs. Sickles lived most of their 40 year marriage apart.

Returning to the states, he was

president of the New York State Board of Civil Service Commissioners, sheriff

of New York and once again representative in the 53rd Congress from 1893 to

1895.

Sickles went on to play an

important part in the preservation of the Gettysburg Battlefield as chairman of

the charity raising money to build a New York State monument at the

battlefield.

In an odd twist of fate he is responsible for buying the original fencing used on East Cemetery Hill to mark the park's borders. The fencing came directly from Lafayette Square where he shot Key.

General Sickles, July 2, 1866, visiting spot where he lost his leg at Battle of Gettysburg.Almost all of the senior generals who fought at Gettysburg have statues at Gettysburg but there isn’t one of Sickles. When asked why Sickles supposedly said, "The entire battlefield is a memorial to Dan Sickles."

A memorial commissioned to

include a bust of Sickles was appropriated but was said to have been embezzled

by Sickles himself. An investigation

found that $27,000 in cash donations was missing. Some wanted Sickle arrested but the Governor

decided that the entire matter was better left alone in the name of the Empire

states reputation and Sickles was allowed to resign from the commission.

Daniel Sickles (seated)

celebrating with veterans at the Rogers House on the Emmetsburg Road during the

1913 reunion. Sickles died the next year. This view was taken circa July 1913.

In March of 1914, a rumor made

the news that Sickles had died but a phone call to his fine Fifth Avenue home

by a reporter was answered by Sickles himself who said that the rumor of his

death was a damn lie and that he was alive and well. Perhaps he wasn’t as well as he thought he

was.

Two months after that call, he suffered a stroke and died on May 3, 1914, at the age of 94. He was buried in Arlington National Cemetery.