Coleman Randolph Hawkins (November

21, 1904 – May 19, 1969), nicknamed "Hawk" and sometimes

"Bean", was a jazz tenor saxophonist. Hawkins' virtuosic, arpeggiated

approach to improvisation, with his characteristic rich, emotional, loud, and

vibrato-laden tonal style, was the main influence on a generation of tenor

players. While Hawkins became well known with swing music during the big band

era, he had a role in the development of bebop in the 1940s. Miles Davis once

said: "When I heard Hawk, I learned to play ballads."

Sculptures of Igor Mitoraj at the exhibition in Pompeii

Igor Mitoraj (March 1944 – October 2014) was a Polish artist and sculptor

known for his fragmented sculptures of the human body often created for

large-scale public installations. Mitoraj's sculptural style is rooted in the

classical tradition with its focus on the well modelled torso. However, Mitoraj

introduced a post-modern twist with ostentatiously truncated limbs, emphasising

the damage sustained by most genuine classical sculptures. Often his works aim

to address the questions of human body, its beauty and fragility, its suffering

as well as deeper aspects of human nature, which as a result of the passing of

time undergo degeneration.

Hell’s Kitchen, 48th Street and Ninth Avenue. Photo by Librado Romero, NYT, 1972.

Well,

That Could Be a Problem

By David

Gonzalez Feb. 1, 2013

One of my first assignments at

The Times was covering Antonio Aguilar’s Rodeo Show at the Kingsbridge Armory

in the Bronx. Aguilar was a singing Mexican cowboy — the Mexican Roy Rogers —

and someone whose movies I saw as a child at the old Freeman Theater on

Southern Boulevard. When I met up with the photographer for the article, I

don’t know what impressed me more: that he actually knew who Aguilar was or

that he lived in the Bronx.

The photographer? Lee Romero. You

know him as Librado, but more about that shortly.

Lee — a Californian by birth and

a New Yorker by love — struck me, a nervous Newsweek refugee, as very

un-Timesean. Needless to say, we hit it off.

Thursday was the staff photographer

Librado Romero’s last day at The Times. His photography (and paintings), some

of which have appeared on Lens, represent just a sliver of his wide-ranging

abilities.

He, too, grew up with the old

Aguilar movies, in Calexico, Calif., where his father, a railroad worker, had

moved the family from Los Angeles. We were both excited to meet the great

Mexican charro, who ushered us into a trailer on the edge of the cavernous

armory. Inside, he regaled us with stories — as he prepared several humongous

syringes he would use on his horses.

I was dumbstruck. Lee did not

take that picture. Our discretion notwithstanding, we got a nice story out of

it, and thus a friendship began.

He had first joined the Times

staff in the late 1960s, teaming with Mike Kaufman to explore corners of the

city in very un-Timesean manners. Once, they rafted down the Bronx River.

Another time they chronicled the carefree life of a 10-year-old in the city.

They turned it into a book.

Kaufman remained a close friend

to his dying day. In a 2009 video in which Lee talked about his photography and

painting, Kaufman lauded Lee, saying, “of all the people I met in the world,

Lee Romero is clearly the most creative.” Trust me, Kaufman met a lot of

people.

Eager to work on bigger things —

and not content to have his farthest travel limited to Staten Island — Lee left

the paper. It is rumored that bosses told him they were grooming him for photo

editor. His reply: “Who cares?”

He had some adventures working for

news magazines. He opened a gallery. He closed a gallery. He worked on a couple

of daily papers in California. He returned to New York, fell in love with Mary

Hardiman and eventually worked his way back to The Times.

I met him around then, when he

was freelancing on the weekends. I liked that he loved music and that his real

passion was painting. In time, I spent hours in his Yonkers studio, where

guitars lay against the assorted artist’s jumble of canvases, crushed paint

tubes and who-knows-what. He became chief photographer at the paper — a title

he declined to use. He spent a lot of time writing a biographical song about

Calexico. Once he asked me to edit it, but I demurred — at 82-odd verses, I

felt overwhelmed. I do remember that he used to eat two-cent tacos as a child.

Sometime in the early years of

our friendship, he changed his byline back to Librado, in honor of his father

and his heritage. So, the artist formerly known as Lee went back to being

Librado Petronilo Romero III.

To spend any time with Lee was to

hear a lot of jokes. Some good. Some bad. Some unprintable. He was relentless,

often suckering you in with a deadpan stare. One of those jokes became a

running punchline.

Years ago he met the Mambo King

himself, Tito Puente. He told the famed percussionist that he, too, played the

drums. That’s interesting, said the maestro.

“But I don’t have any rhythm,”

Lee said.

“Well,” Puente replied. “That

could be a problem.”

Ever since that day, I have

tossed out that line as Tito’s all-purpose wisdom for the ages.

Thursday was Lee’s last day at

the paper. He has taken a buyout. He will paint, play music, drive a fast car

and tell bad jokes. He will enjoy his son Conor’s new role playing Michael J.

Fox’s son in an NBC sitcom. He will travel with Mary, a picture editor at the

Times who took a buyout in 2011. He will still live in the Bronx, and he will

still be my friend.

But a New York Times without

Librado Petronilo Romero III? Well, that

could be a problem.

The Pleasure of Writing by A.A. Milne

Sometimes

when the printer is waiting for an article which really should have been sent

to him the day before, I sit at my desk and wonder if there is any possible

subject in the whole world upon which I can possibly find anything to say. On

one such occasion I left it to Fate, which decided, by means of a dictionary

opened at random, that I should deliver myself of a few thoughts about

goldfish. (You will find this article later on in the book.) But to-day I do

not need to bother about a subject. To-day I am without a care. Nothing less

has happened than that I have a new nib in my pen.

In the

ordinary way, when Shakespeare writes a tragedy, or Mr. Blank gives you one of

his charming little essays, a certain amount of thought goes on before pen is

put to paper. One cannot write "Scene I. An Open Place. Thunder and

Lightning. Enter Three Witches," or "As I look up from my window, the

nodding daffodils beckon to me to take the morning," one cannot give of

one's best in this way on the spur of the moment. At least, others cannot. But

when I have a new nib in my pen, then I can go straight from my breakfast to

the blotting-paper, and a new sheet of foolscap fills itself magically with a

stream of blue-black words. When poets and idiots talk of the pleasure of writing,

they mean the pleasure of giving a piece of their minds to the public; with an

old nib a tedious business. They do not mean (as I do) the pleasure of the

artist in seeing beautifully shaped "k's" and sinuous "s's"

grow beneath his steel. Anybody else writing this article might wonder

"Will my readers like it?" I only tell myself "How the

compositors will love it!"

But

perhaps they will not love it. Maybe I am a little above their heads. I

remember on one First of January receiving an anonymous postcard wishing me a

happy New Year, and suggesting that I should give the compositors a happy New

Year also by writing more generously. In those days I got a thousand words upon

one sheet 8 in. by 5 in. I adopted the suggestion, but it was a wrench; as it

would be for a painter of miniatures forced to spend the rest of his life

painting the Town Council of Boffington in the manner of Herkomer. My canvases

are bigger now, but they are still impressionistic. "Pretty, but what is

it?" remains the obvious comment; one steps back a pace and saws the air

with the hand; "You see it better from here, my love," one says to

one's wife. But if there be one compositor not carried away by the mad rush of

life, who in a leisurely hour (the luncheon one, for instance) looks at the

beautiful words with the eye of an artist, not of a wage-earner, he, I think,

will be satisfied; he will be as glad as I am of my new nib. Does it matter,

then, what you who see only the printed word think of it?

A woman,

who had studied what she called the science of calligraphy, once offered to

tell my character from my handwriting. I prepared a special sample for her; it

was full of sentences like "To be good is to be happy," "Faith

is the lode- star of life," "We should always be kind to

animals," and so on. I wanted her to do her best. She gave the morning to

it, and told me at lunch that I was "synthetic." Probably you think

that the compositor has failed me here and printed "synthetic" when I

wrote "sympathetic." In just this way I misunderstood my

calligraphist at first, and I looked as sympathetic as I could. However, she

repeated "synthetic," so that there could be no mistake. I begged her

to tell me more, for I had thought that every letter would reveal a secret, but

all she would add was "and not analytic." I went about for the rest

of the day saying proudly to myself "I am synthetic! I am synthetic! I am

synthetic!" and then I would add regretfully, "Alas, I am not

analytic!" I had no idea what it meant.

And how

do you think she had deduced my syntheticness? Simply from the fact that, to

save time, I join some of my words together. That isn't being synthetic, it is

being in a hurry. What she should have said was, "You are a busy man; your

life is one constant whirl; and probably you are of excellent moral character

and kind to animals." Then one would feel that one did not write in vain.

My pen is

getting tired; it has lost its first fair youth. However, I can still go on. I

was at school with a boy whose uncle made nibs. If you detect traces of

erudition in this article, of which any decent man might be expected to be

innocent, I owe it to that boy. He once told me how many nibs his uncle made in

a year; luckily I have forgotten. Thousands, probably. Every term that boy came

back with a hundred of them; one expected him to be very busy. After all, if

you haven't the brains or the inclination to work, it is something to have the

nibs. These nibs, however, were put to better uses. There is a game you can

play with them; you flick your nib against the other boy's nib, and if a lucky

shot puts the head of yours under his, then a sharp tap capsizes him, and you

have a hundred and one in your collection. There is a good deal of strategy in

the game (whose finer points I have now forgotten), and I have no doubt that

they play it at the Admiralty in the off season. Another game was to put a

clean nib in your pen, place it lightly against the cheek of a boy whose head

was turned away from you, and then call him suddenly. As Kipling says, we are

the only really humorous race. This boy's uncle died a year or two later and

left about £80,000, but none of it to his nephew. Of course, he had had the

nibs every term. One mustn't forget that.

The nib I

write this with is called the "Canadian Quill"; made, I suppose, from

some steel goose which flourishes across the seas, and which Canadian

housewives have to explain to their husbands every Michaelmas. Well, it has

seen me to the end of what I wanted to say—if indeed I wanted to say anything.

For it was enough for me this morning just to write; with spring coming in

through the open windows and my good Canadian quill in my hand, I could have

copied out a directory. That is the real pleasure of writing.

Antonio Vivaldi – The Four Seasons, Op. 8, "Spring": Allegro

The Four Seasons

WRITTEN BY

Betsy Schwarm

Betsy Schwarm is a music

historian based in Colorado. She serves on the music faculty of Metropolitan

State University of Denver and gives pre-performance talks for Opera Colorado

and the Colorado Symphony.

The Four Seasons, Italian Le

quattro stagioni, group of four violin concerti by Italian composer Antonio

Vivaldi, each of which gives a musical expression to a season of the year. They

were written about 1720 and were published in 1725 (Amsterdam), together with

eight additional violin concerti, as Il cimento dell’armonia e dell’inventione

(“The Contest Between Harmony and Invention”).

In which city did Ludwig van

Beethoven give his first public performance as an adult?

The Four Seasons is the best

known of Vivaldi’s works. Unusually for the time, Vivaldi published the

concerti with accompanying poems (possibly written by Vivaldi himself) that

elucidated what it was about those seasons that his music was intended to

evoke. It provides one of the earliest and most-detailed examples of what was

later called program music—music with a narrative element.

Vivaldi took great pains to

relate his music to the texts of the poems, translating the poetic lines

themselves directly into the music on the page. In the middle section of the

Spring concerto, where the goatherd sleeps, his barking dog can be marked in

the viola section. Other natural occurrences are similarly evoked. Vivaldi

separated each concerto into three movements, fast-slow-fast, and likewise each

linked sonnet into three sections. His arrangement is as follows:

Spring (Concerto No. 1 in E

Major)

Allegro

Spring has arrived with joy

Welcomed by the birds with happy

songs,

And the brooks, amidst gentle

breezes,

Murmur sweetly as they flow.

The sky is caped in black, and

Thunder and lightning herald a

storm

When they fall silent, the birds

Take up again their delightful

songs.

Largo e pianissimo sempre

And in the pleasant,

blossom-filled meadow,

To the gentle murmur of leaves

and plants,

The goatherd sleeps, his faithful

dog beside him.

Allegro

To the merry sounds of a rustic

bagpipe,

Nymphs and shepherds dance in

their beloved spot

When Spring appears in splendour.

Summer (Concerto No. 2 in G

Minor)

Allegro non molto

Under the merciless sun of the

season

Languishes man and flock, the

pine tree burns.

The cuckoo begins to sing and at

once

Join in the turtledove and the

goldfinch.

A gentle breeze blows, but Boreas

Is roused to combat suddenly with

his neighbour,

And the shepherd weeps because

overhead

Hangs the fearsome storm, and his

destiny.

Adagio

His tired limbs are robbed of

rest

By his fear of the lightning and

the frightful thunder

And by the flies and hornets in

furious swarms.

Presto

Alas, his fears come true:

There is thunder and lightning in

the heavens

And the hail cuts down the tall

ears of grain.

Autumn (Concerto No. 3 in F

Major)

Allegro

The peasant celebrates with

dancing and singing

The pleasure of the rich harvest,

And full of the liquor of Bacchus

They end their merrymaking with a

sleep.

Adagio molto

All are made to leave off dancing

and singing

By the air which, now mild, gives

pleasure

And by the season, which invites

many

To find their pleasure in a sweet

sleep.

Allegro

The hunters set out at dawn, off

to the hunt,

With horns and guns and dogs they

venture out.

The beast flees and they are

close on its trail.

Already terrified and wearied by

the great noise

Of the guns and dogs, and wounded

as well

It tries feebly to escape, but is

bested and dies.

Winter (Concerto No. 4 in F

Minor)

Allegro non molto

Frozen and shivering in the icy

snow,

In the severe blasts of a

terrible wind

To run stamping one’s feet each

moment,

One’s teeth chattering through

the cold.

Largo

To spend quiet and happy times by

the fire

While outside the rain soaks

everyone.

To walk on the ice with tentative

steps,

Going carefully for fear of

falling.

To go in haste, slide, and fall

down to the ground,

To go again on the ice and run,

In case the ice cracks and opens.

To hear leaving their iron-gated

house Sirocco,

Boreas, and all the winds in

battle—

This is winter, but it brings

joy.

Folk Music: The Almanac Singers

The Almanacs were really the first folk music supergroup and spun

off into successful careers for Woody Guthrie, Pete Seeger, Lee Hays,

Josh White, Burl Ives, and various other folks who made up the core of the

group or who joined them on occasion. Seeger and Hays went on to form The

Weavers.

Roman Architecture: Famous Buildings from Ancient Rome

Sarah Buckley

Roman Architecture

What is Roman Architecture?

Roman architecture adopted the external language of classical

Greek architecture for the purposes of the ancient Romans, but was different

from Greek buildings, becoming a new architectural style. The two styles are

often considered one body of classical architecture. Roman architecture

flourished in the Roman Republic and even more so under the Empire, when the

great majority of surviving buildings were constructed, some of which the ruins

remain, to which we’ve researched and learned..

What was it famous for?

Ancient Roman architecture used new materials, particularly

concrete, and newer technologies such as the arch and the dome to make

buildings that were typically strong and well-engineered. Large numbers remain

in some form across the empire, sometimes complete and still in use to this

day.

How popular is it outside of Rome?

In Europe the Italian Renaissance saw a conscious revival of

correct classical styles, initially purely based on Roman examples. Numerous

local classical styles developed, such as Palladian architecture, Georgian

architecture and Regency architecture in the English-speaking world, Federal

architecture in the United States, and later Stripped Classicism and PWA

Moderne.

Roman influences may be found around us today, in banks, government buildings, great houses, and even small houses, perhaps in the form of a porch with Doric columns and a pediment or in a fireplace or a mosaic shower floor derived from a Roman original, often from Pompeii or Herculaneum. The mighty pillars, dome and arches of Rome echo in the New World too, where in Washington, D.C. stand the Capitol building, the White House, the Lincoln Memorial, and other government buildings. All across the US the seats of regional government were normally built in the grand traditions of Rome, with vast flights of stone steps sweeping up to towering pillared porticoes, with huge domes gilded or decorated inside with the same or similar themes that were popular in Rome.

Roman influences may be found around us today, in banks, government buildings, great houses, and even small houses, perhaps in the form of a porch with Doric columns and a pediment or in a fireplace or a mosaic shower floor derived from a Roman original, often from Pompeii or Herculaneum. The mighty pillars, dome and arches of Rome echo in the New World too, where in Washington, D.C. stand the Capitol building, the White House, the Lincoln Memorial, and other government buildings. All across the US the seats of regional government were normally built in the grand traditions of Rome, with vast flights of stone steps sweeping up to towering pillared porticoes, with huge domes gilded or decorated inside with the same or similar themes that were popular in Rome.

History

While borrowing much from the preceding Etruscan architecture,

such as the use of hydraulics and the construction of arches, Roman prestige

architecture remained firmly under the spell of Ancient Greek architecture and

the classical orders. This came initially from Magna Graecia, the Greek

colonies in southern Italy, and indirectly from Greek influence on the

Etruscans, but after the Roman conquest of Greece directly from the best

classical and Hellenistic examples in the Greek world. The influence is evident

in many ways; for example, in the introduction and use of the Triclinium in

Roman villas and terraces as a place and manner of dining. Roman builders

employed Greeks in many capacities, especially in the great boom in

construction in the early Empire.

Roman architecture covers the period from the establishment of the

Roman Republic in 509 BC to about the 4th century AD, after which it becomes

reclassified as Late Antique or Byzantine architecture. Almost no substantial

examples survive from before about 100 BC, and most of the major survivals are

from the later empire, after about 100 AD. Roman architectural style continued

to influence building in the former empire for many centuries, and the style

used in Western Europe beginning about 1000 is called Romanesque architecture

to reflect this dependence on basic Roman forms.

Corinthian Roman architecture

The word "Corinthian" describes an ornate column style

developed in ancient Greece and classified as one of the Classical Orders of

Architecture. The Corinthian style is more complex and elaborate than the earlier

Doric and Ionic Orders. The capital or top part of a Corinthian style column

has lavish ornamentation carved to resemble leaves and flowers. Roman architect

Vitruvius observed that the delicate Corinthian design "was produced out

of the two other orders."

Doric Roman architecture

The Doric Order was the first style of Classical Architecture,

which is the sophisticated architectural styles of ancient Greece and Rome that

set the standards for beauty, harmony, and strength for European architecture.

The other two orders are Ionic and Corinthian. Doric Order is recognizable by

two basic features: the columns and the entablature.

Ionic Roman architecture

The Ionic capital is characterized by the use of volutes. The

Ionic columns normally stand on a base which separates the shaft of the column

from the stylobate or platform while the cap is usually enriched with

egg-and-dart.

The ancient architect and architectural historian Vitruvius associates the Ionic with feminine proportions (the Doric representing the masculine).

The ancient architect and architectural historian Vitruvius associates the Ionic with feminine proportions (the Doric representing the masculine).

Famous Roman architects

Any list of Roman architects has to begin with a single name:

Marcus Vitruvius Pollio. Vitruvius was not just a Roman architect, he was the

Roman architect. So, what made Vitruvius so great? Well, Vitruvius was the

architect of Julius Caesar from 58 to 51 BCE. Not only did he build several

structures, but he also traveled extensively around the Mediterranean and

studied architecture from a theoretical perspective. The result was a major

text entitled De Architectura, written between 30 and 20 BCE.

De Architectura was the first major Roman treatise on

architecture, and in it Vitruvius tackles several issues. For one, he outlined

the architectural styles of the Greeks, and organized them into what we call

the Greek orders of architecture. He discussed building in terms of math and

science, as well as philosophy, arts, and social welfare. He saw architecture

as a unification of arts and sciences, in which the final product could help

create a more ideal society.

After Vitruvius, there were many architects who helped Rome grow.

Only one, however, can really be said to rival Vitruvius's fame. Apollodorus of

Damascus was a 2nd century CE architect from Damascus, then part of the Roman

Empire (today part of Syria). Apollodorus was the favored architect of the

emperor Trajan, who ruled from 98-117 CE. Under Trajan, Rome stretched its

imperial borders further than ever before. Trajan celebrated the success and

wealth of Rome by commissioning a large number of building projects, most of

them executed by Apollodorus.

This monumental arch was constructed in 203 AD in recognition of

the unprecedented Roman victories over the Parthians in the dying years of the

second century. It was under Septimius Severus’ rule that Rome was able to successfully

suppress a raging civil war among its neighboring states. But the icing on the

cake came when he immediately declared war on the Parthian Empire and brought

the Parthians to their knees. In recognition of his achievements, the Roman

Senate had one of the most beautifully decorated triumphal arches erected on

his return to Rome.

Originally, it had a bronze gilded inscription as homage to Septimius and his two sons Caracalla and Geta for having restored and expanded the Roman Republic. It was a unique triumphal monument by all standards in contemporary Rome. Even today, despite some heavy damage, it stands as a lasting reminder of the once flamboyant Roman Republic.

Originally, it had a bronze gilded inscription as homage to Septimius and his two sons Caracalla and Geta for having restored and expanded the Roman Republic. It was a unique triumphal monument by all standards in contemporary Rome. Even today, despite some heavy damage, it stands as a lasting reminder of the once flamboyant Roman Republic.

9. Temples of Baalbek

A major attraction and a remarkable archaeological site in

present-day Lebanon, Baalbek is considered as one of the most spectacular

wonders of the ancient world. It also happens to be one of the largest, most

prestigious, and mostwell-preserved Roman temples built in the ancient Roman

era. The first of the Baalbek temples was constructed in the first century BC

and over the next 200 years, the Romans built three more, each dedicated to the

gods Jupiter, Bacchus, and Venus respectively.

The largest temple among them was the Temple of Jupiter, which had 54 huge granite columns, each one around 70 feet (21 meters) tall. Although only six of these columns survive today, their sheer scale is enough to show the majesty of the Baalbek temples. After the fall of Rome, the Baalbek temples suffered from theft, war, and natural disaster, but they are still able to conjure up the aura of magnificence to this day, with thousands of people visiting the famous Baalbek temples every year.

The largest temple among them was the Temple of Jupiter, which had 54 huge granite columns, each one around 70 feet (21 meters) tall. Although only six of these columns survive today, their sheer scale is enough to show the majesty of the Baalbek temples. After the fall of Rome, the Baalbek temples suffered from theft, war, and natural disaster, but they are still able to conjure up the aura of magnificence to this day, with thousands of people visiting the famous Baalbek temples every year.

8. Library of Celsus

Named after the famous former governor of the city of Ephesus, the

Library of Celsus was actually a monumental tomb dedicated to Gaius Julius

Celsus Polemaeanus. This amazing piece of Roman architecture was constructed on

the orders of Celsus’ son Galius Julius Aquila. It was also a popular

repository for important documents and at the height of its use, the Library of

Celsus housed over 12,000 different scrolls.

It had beautifully carved interiors and equally mesmerizing architectural designs on the exterior, making it one of the most impressive buildings in the ancient Roman Empire. The architecture of the library is typically reminiscent of the building style that was popular during the rule of Emperor Hadrian. The entire structure is supported by a nine-step podium which is 69 feet (21 meters) long. The surviving facade of the building retains its amazing decorations and relief carvings which only add to the grandeur of the structure.

It had beautifully carved interiors and equally mesmerizing architectural designs on the exterior, making it one of the most impressive buildings in the ancient Roman Empire. The architecture of the library is typically reminiscent of the building style that was popular during the rule of Emperor Hadrian. The entire structure is supported by a nine-step podium which is 69 feet (21 meters) long. The surviving facade of the building retains its amazing decorations and relief carvings which only add to the grandeur of the structure.

7. Pont du Gard

The Pont du Gard, literally the Gard bridge, is one of the few

surviving aqueducts constructed during the Roman Empire. Located in present-day

southern France, it was built somewhere in the middle of the first century AD.

This aqueduct was constructed without the use of any mortar; Roman engineers

built this three-story masterpiece by fitting together massive blocks of

precisely cut stones. These huge blocks of stone weighed up to six tonnes each,

and the bridge itself measured up to 1180 feet (360 meters) at its highest

point.

The Pont du Gard was a pivotal structure in an aqueduct that stretched over 31 miles (50 kilometers) in length. The success of this engineering marvel was essential in making the entire aqueduct functional because it supplied water to the city of Nimes. In the end, the Roman engineers pulled off an outstanding feat of contemporary engineering and hydraulics. The Pont du Gard has been used as a conventional bridge throughout the Middle Ages, right up until the 18th century.

The Pont du Gard was a pivotal structure in an aqueduct that stretched over 31 miles (50 kilometers) in length. The success of this engineering marvel was essential in making the entire aqueduct functional because it supplied water to the city of Nimes. In the end, the Roman engineers pulled off an outstanding feat of contemporary engineering and hydraulics. The Pont du Gard has been used as a conventional bridge throughout the Middle Ages, right up until the 18th century.

6. Aqueduct of Segovia

Located on the Iberian peninsula, the Aqueduct of Segovia still

retains its structural integrity to this day, making it one of the

best-preserved pieces of architecture from ancient Rome. It was built somewhere

around 50 AD to facilitate the flow of drinking water from the River Frio to

the city of Segovia. On its completion, it was an unprecedented 16km-long

structure built using around 24,000 giant blocks of granite.

Just like the Pont du Gard, Roman engineers built the entire structure without any mortar. With 165 arches, all of which are over 30 feet (9 meters) in height, this architectural phenomenon has been a symbol of Segovia for centuries. The aqueduct had to go through an extended period of reconstruction during the 15th and 16th centuries after years of use and structural neglect. By the 1970s and 1990s, some urgent and necessary conservation action was undertaken to preserve the monument and its glory.

Just like the Pont du Gard, Roman engineers built the entire structure without any mortar. With 165 arches, all of which are over 30 feet (9 meters) in height, this architectural phenomenon has been a symbol of Segovia for centuries. The aqueduct had to go through an extended period of reconstruction during the 15th and 16th centuries after years of use and structural neglect. By the 1970s and 1990s, some urgent and necessary conservation action was undertaken to preserve the monument and its glory.

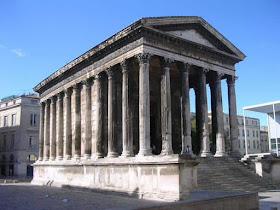

5. Maison Carrée

Maison Carrée is the only temple constructed in the time of

ancient Rome that is completely preserved to this day. This marvel of Roman

engineering was built around 16 BC in the city of Nimes. Maison Carrée is an

architectural gem that stands 49 feet (15 meters) tall and runs along a length

of 85 feet (26 meters). It was built by Roman General Marcus Vipanius Agrippa

in memory of his two sons who died young. With the imminent fall of the Roman

Empire on the horizon, Maison Carrée was given a fresh lease of life when it

was turned into a Christian church in the fourth century.

This decision spared this majestic temple from the neglect and destruction faced by many other Roman monuments and landmarks. Since then, it has been used for various purposes such as a town hall, stable, and storehouse. At present, it is a museum.

This decision spared this majestic temple from the neglect and destruction faced by many other Roman monuments and landmarks. Since then, it has been used for various purposes such as a town hall, stable, and storehouse. At present, it is a museum.

4. Diocletian’s Palace

This marvelous building was built by the famous Roman emperor

Diocletian in preparation for his retirement. Diocletian was the first Roman

emperor who voluntarily retired from his position, citing declining health

issues. After his retirement on May 1, 305 AD, he went on to spend a quiet life

in this majestic palace.

The palace covers around 705 feet (215 meters) from east to west and its walls are about 85 feet (26 meters) high. At a time when the Roman civilization was in transition from the classical to the medieval era, architects were able to incorporate different building styles that had been used over the ages. It also helped that Christians used the palace as a cathedral in the Middle Ages, preserving its structural integrity throughout the medieval period. At present, Diocletian’s Palace is one of the most popular archaeological attractions in Croatia, and also a world heritage site as declared by UNESCO.

The palace covers around 705 feet (215 meters) from east to west and its walls are about 85 feet (26 meters) high. At a time when the Roman civilization was in transition from the classical to the medieval era, architects were able to incorporate different building styles that had been used over the ages. It also helped that Christians used the palace as a cathedral in the Middle Ages, preserving its structural integrity throughout the medieval period. At present, Diocletian’s Palace is one of the most popular archaeological attractions in Croatia, and also a world heritage site as declared by UNESCO.

3. Amphitheater, Nimes

When this famous amphitheater was built in the city of Nimes, the

city was known by the name of Nemausus. From around 20 BC, Augustus started to

populate the city and give it a structure more akin to a typical Roman state.

It had a number of splendid buildings, a surrounding wall, more than 200

hectares of land, and a majestic theater at its heart. Better known as the

Arena of Nimes, this astoundingly large theater had a seating capacity of

around 24,000, effectively making it one of the biggest amphitheaters in Gaul.

It was so large that during the Middle Ages, a small fortified

palace was built within it. Later, somewhere around 1863, the arena was

remodeled into a huge bullring. It is still used to host annual bullfights to

this day.

2. Pantheon

The Pantheon is arguably the most well-preserved architectural

marvel from the ancient Roman era. Unlike many other contemporary Roman temples

that were almost always dedicated to particular Roman deities, the Pantheon was

a temple for all the Roman gods. The construction of this temple was completed

in 125 AD during the rule of Hadrian.

The Pantheon has a large circular portico that opens up to a rotunda. The rotunda is covered by a majestic dome that adds a whole new dimension to its grandeur. The sheer size and scale of this dome is a lasting testimony to the skills of ancient Roman architects and engineers. The fact that this astounding piece of engineering still stands to this day, surviving 2,000 years’ worth of corrosion and natural disasters, speaks volumes for its build quality.

The Pantheon has a large circular portico that opens up to a rotunda. The rotunda is covered by a majestic dome that adds a whole new dimension to its grandeur. The sheer size and scale of this dome is a lasting testimony to the skills of ancient Roman architects and engineers. The fact that this astounding piece of engineering still stands to this day, surviving 2,000 years’ worth of corrosion and natural disasters, speaks volumes for its build quality.

1. Roman Colosseum

When the famous amphitheater, the Colosseum, was built in ancient

Rome, it had an area of 620 by 523 feet (189 by 159 meters)), making it the

largest amphitheater of its time. The construction of the Colosseum, the largest

and most popular ancient Roman monument, began during the reign of Emperor

Vespasian in 72 AD. By the time it was finished by his son Titus in 80 AD, a

never-before-seen amphitheater with a seating capacity of over 50,000 was ready

for use.

It could accommodate such large numbers of spectators that as many 80 different entrances were installed. It is said that its opening ceremony – the grandest of all spectacles – lasted for about 100 days. In that time, about 5,000 animals and 2,000 gladiators fought to their deaths in an unprecedented extravaganza of gladiatorial and bestiarius battles.

It could accommodate such large numbers of spectators that as many 80 different entrances were installed. It is said that its opening ceremony – the grandest of all spectacles – lasted for about 100 days. In that time, about 5,000 animals and 2,000 gladiators fought to their deaths in an unprecedented extravaganza of gladiatorial and bestiarius battles.

Read it, learn it, live it.

“Write. Don't talk about writing.

Don't tell me about your wonderful story ideas. Don't give me a bunch of 'somedays'.

Plant your ass and scribble, type, keyboard. If you have any talent at all it

will leak out despite your failure to pay attention in English."

The Instrumentalities of the

Night: An Interview with Glen Cook, The SF Site, September 2005.

"No Tool or Rope or Pail," by Bob Arnold

It hardly mattered what time of year

We passed their farmhouse,

They never waved,

This old farm couple

Usually bent over in the vegetable garden

Or walking by the muddy dooryard

Between house and red-weathered barn.

They would look up, see who was passing,

Then look back down, ignorant to the event.

We would always wave nonetheless,

Before you dropped me off at work

Further up on the hill,

Toolbox rattling in the backseat,

And then again on the way home

Later in the day, the pale sunlight

High up in their pasture,

Our arms out the window,

Cooling ourselves.

And it was that one midsummer evening

We drove past and caught them sitting

together on the front porch

At ease, chores done,

The tangle of cats and kittens

Cleaning themselves of fresh spilled milk

On the barn door ramp;

We drove by and they looked up—

The first time I've ever seen their

Hands free of any work,

No too or rope or pail—

And they waved.