Under the Third Avenue El, New York, Photo by Rebecca Lepkoff, 1947

Rebecca Lepkoff (born Rebecca Brody; August 4, 1916 – August 17,

2014) was n photographer. She is best known for her images depicting daily life

in the Lower East Side neighborhood of New York City in the 1940s. Fascinated

by the area where she lived, she first photographed Essex and Hester Street

which, she recalls, "were full of pushcarts." They no longer exist

today but then "everyone was outside: the mothers with their baby

carriages, and the men just hanging out." Her photographs captured people

in the streets, especially children, as well as the buildings and the signs on

store fronts Lepkoff died Sunday, August 17, 2014, at her home in Townshend,

Vermont. Two weeks prior to her death, she had turned 98.

Babylon Revisited: When the money runs out. By Azra Raza

One of the finest short stories in the English language, 'Babylon Revisited’, written by F Scott Fitzgerald after the Great Crash, is an intensely personal portrait of a man who has squandered his life. It’s also a perfect tale for the times we live in .

One of the finest short stories in the English language, 'Babylon

Revisited’, written by F Scott Fitzgerald after the Great Crash, is an

intensely personal portrait of a man who has squandered his life. It’s also a

perfect tale for the times we live in .

Today, Francis Scott Key

Fitzgerald may be one of America’s most celebrated novelists, but during his

lifetime, he was best known as a writer of short stories. At the end of the

Twenties, he was the highest-paid writer in America earning fees of $4,000 per

story (about $50,000 today) and published in mainstream magazines such as The

Saturday Evening Post. Over 20 years, he wrote almost 200 stories in addition

to his four novels, publishing 164 of them in magazines.

When Ernest Hemingway first met Fitzgerald, in Paris in 1925, it

was within weeks of the publication of The Great Gatsby; Hemingway later wrote

that before reading Gatsby, he thought that Fitzgerald “wrote Saturday Evening

Post stories that had been readable three years before, but I never thought of

him as a serious writer”.

Gatsby would change all that, of course, so thoroughly that now we

may be in danger of forgetting Fitzgerald’s stories. The haste in which he

wrote them, in order to pay for the luxurious lifestyle he enjoyed with his

wife, Zelda, means that the stories are uneven in quality, but at their best

they are among the finest stories in English. And “Babylon Revisited”, a

Saturday Evening Post story first published exactly 80 years ago next month –

and free inside next Saturday’s edition of the Telegraph – is probably the

greatest. A tale of boom and bust, about the debts one has to pay when the

party comes to an end, it is a story with particular relevance for the way we

live now.

Fitzgerald’s fortunes uncannily mirrored the fortunes of the

nation he wrote about: his first novel, This Side of Paradise, became a runaway

bestseller in early 1921, just as America entered the boom period that

Fitzgerald himself would name the Jazz Age. He and Zelda became celebrities and

began living the high life. They were the golden couple of the Twenties,

“beautiful and damned”, as the prophetic title of Fitzgerald’s 1922 novel

suggested, treated like royalty in America’s burgeoning celebrity culture.

Glamorous, reckless and profligate, the Fitzgerald’s were spendthrift in every

sense. Much later, Fitzgerald would have to take account of all they had

squandered – not only wealth, but beauty, youth, health, and even his genius.

In early 1924, the Fitzgerald’s sailed from New York with their

three-year-old daughter, Scottie, for Europe, where they joined the growing

crowd of American expatriates enjoying the comparatively cheap cost of living

in post First World War Paris and the Riviera. There they became friends with

Hemingway, as well as with other writers and artists of the day. Fitzgerald’s

biographers record that while in Paris, Fitzgerald’s routine was to rise at

11am, and begin work at 5pm. He claimed to write most days until 3am, but the

reality was that usually he and Zelda could be found among the cabarets and

clubs of Montmartre and the Left Bank, where they drank, danced, flirted and

fought into the small hours

When the Great Crash came at the end of 1929, the Fitzgerald’s

crashed also, just as they had roared along with the Roaring Twenties. In April

1930, Zelda had a nervous breakdown and was eventually diagnosed with

schizophrenia; she would spend the rest of her life in and out of psychiatric

hospitals.

And in the early Thirties, as America sank into Depression,

Fitzgerald found himself battling depression. His alcoholism was spiraling out

of control, his stories were now abruptly out of key with the mood of the

nation, and he found it increasingly difficult to earn enough to pay for

Zelda’s medical care and their daughter’s education.

Written in December 1930, just eight months after Zelda’s

breakdown, the elegiac “Babylon Revisited” is Fitzgerald’s exquisitely painful

meditation on what he had wasted, his recognition that the cost of living it

large is not just financial but emotional, psychological and spiritual – and that

one can’t live in arrears forever.

That Christmas, Fitzgerald brought Scottie to visit her mother in

a Swiss sanatorium, but Zelda’s erratic behavior frightened the nine-year-old

girl; Scott took his daughter skiing for the rest of her school holiday.

“Babylon Revisited”, written just as Fitzgerald faced the prospect

that Zelda might be lost to him for good, and in fear for his ability to care

for his daughter, is itself a kind of reckoning of the price one has to pay.

Financial debts, paying the price for past extravagance, becomes a metaphor for

moral debts, the loss of one’s sense of character or one’s personal credit with

the world.

The tale of a man who has lost everything but is fighting to

redeem himself, “Babylon Revisited” concerns Charlie Wales, an American

expatriate who lives a profligate life in Paris during the Twenties. One night

during a bacchanalian spree, he quarrels with his wife, Helen, and she

retaliates by kissing another man. Charlie storms home alone and Helen arrives

home an hour later, too drunk and disoriented to find a taxi. She dies soon

after; Charlie has a breakdown and is institutionalized before losing all his

money in the crash.

Their daughter, Honoria, goes to live with Helen’s sister Marion.

As the story opens three years later, Charlie has returned to Paris sober,

financially successful again and determined to pull his life together. He has

come to reclaim his symbolically named daughter: if honor is restored to him

perhaps he can salvage something from the wreckage of his life.

“Babylon Revisited” clearly chimes with Fitzgerald’s own life in

late 1930: the extravagant dissipation of life in Paris during the boom years;

the wife lost to illness; a fortune frittered away in the confidence that “even

when you were broke, you didn’t worry about money,” as Fitzgerald later wrote

about the rampant spending in the Twenties, “because it was in such profusion

around you.” And it is a story about a father’s recognition that, especially in

the absence of her mother, his daughter needs him to face up to his

responsibilities.

Fitzgerald carefully patterns the story so that it comes full

circle, and Charlie ends where he began, in the Paris Ritz Bar. The setting is

emblematically appropriate, suggesting Charlie’s twin crimes: his careless

squandering of wealth and his drinking. But beginning and ending in the same

location also hints at one of the story’s deeper themes: Charlie will end up

where he began, borne back ceaselessly into the past, as Fitzgerald wrote at

the end of The Great Gatsby. For Charlie Wales revisiting Babylon does not

bring closure; coming full circle merely creates a spiraling sense of loss.

Throughout “Babylon Revisited”, Fitzgerald uses economic metaphors

to underscore the idea that debts must be paid. The story reverberates with

uncanny echoes – or rather, anticipations – of our own era, the way in which we

trusted that living on credit could last forever. What Fitzgerald shows us is

the effects that this mistake has not only on our economy, but on our characters:

that money is the least of what we have to lose.

The poignancy of the story derives from its sense of injustice: a

recovering alcoholic is trying to prove that he’s reformed and if we feel from

the outset of the story a sense of impending doom, we might predict that

Charlie will fall off the wagon. But Fitzgerald twists the knife by making

Charlie’s reformation authentic: he has accepted his responsibilities by coming

back to face the past, own up to his mistakes and remedy them by repairing what’s

left of his family. But that may not be enough.

At one point during his stay in Paris, Charlie revisits his old

haunts on the Left Bank and understands at last: “I spoiled this city for

myself. I didn’t realize it, but the days came along one after another, and

then two years were gone, and everything was gone, and I was gone.” He has got

himself back but the question the story poses is whether everything is gone for

good.

Wandering through Montmartre, Charlie suddenly realizes the extent

of his wastefulness in what is perhaps the most superb passage in this tale:

“All the catering to vice and waste was on an utterly childish scale, and he

suddenly realized the meaning of the word 'dissipate’ – to dissipate into thin

air; to make nothing out of something. In the little hours of the night every

move from place to place was an enormous human jump, an increase of paying for

the privilege of slower and slower motion. He remembered thousand-franc notes

given to an orchestra for playing a single number, hundred-franc notes tossed

to a doorman for calling a cab. But it hadn’t been given for nothing. It had

been given, even the most wildly squandered sum, as an offering to destiny that

he might not remember the things most worth remembering, the things that now he

would always remember – his child taken from his control, his wife escaped to a

grave in Vermont.”

The idea of “dissipation” as an active loss is perhaps the story’s

central insight, and it is one to which Fitzgerald would return again and again

in his fiction of the Thirties. The passage evokes the sense of vanished and

wasted time, the remorse that characterizes the morning after the night before,

the sense of everything being spent.

“Babylon Revisited” is at once timeless and startlingly modern in

its evocation of a single father struggling with alcoholism and trying to care

for his daughter and coming to terms with the costs of extravagance. Part of

the tale’s poignancy is Fitzgerald’s recognition that the tragedy is not just

Charlie’s: it is also his daughter’s. When Charlie comes to ask Marion to

return Honoria to him, he realizes Marion is bitter, particularly because of

Charlie’s easy acquisition of wealth.

Marion says she is “delighted” that Americans have deserted Paris

following the crash: “Now at least you can go into a store without their

assuming you’re a millionaire.” Charlie’s response is revealing: “But it was

nice while it lasted… We were a sort of royalty, almost infallible, with a sort

of magic around us.” Only it didn’t last long: they wasted their “sort of

magic” in search of a life that could never be as magnificent as their hopes,

just as surely as Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald did.

Nine years after the publication of “Babylon Revisited”, less than

a year before he would die at 44, Fitzgerald wrote his daughter Scottie a

letter about the story: “You have earned some money for me this week because I

sold 'Babylon Revisited,’ in which you are a character, to the pictures (the

sum received wasn’t worthy of the magnificent story – neither of you nor of me

– however, I am accepting it).”

Like Charlie, Fitzgerald learnt

the hard way that loss is remorseless, absolute; what has been wasted is

irrecoverable. But as “Babylon Revisited” also shows, even out of the wreckage

some things can be salvaged, if not everything: what Fitzgerald retrieved he

bequeathed to us, the hard-won lessons of his life transformed into

heartbreaking art.

Dina Vierny

Dina Vierny was a muse to French sculptor Aristide Maillol and model for painters Henri Matisse and Pierre Bonnard. Vierny, who began modeling for Maillol at age 15, was his greatest fan and a leading force in making his acclaimed figurative bronzes available to the public.

(From The Guardian)

When an artist refers to his

model as his muse, it is usually his way of dignifying their joint extramural

activities. But in the case of Aristide Maillol's model Dina Vierny, who has

died aged 89, she genuinely was his muse, not his mistress. She met him in

1934, when she was 15 and he was 73, and inspired a fresh direction in his

sculpture - most evident in The River, one cast of which is on display in the

Tuileries gardens in Paris, while another sprawls on the ledge of a pond in the

garden of the Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Her death breaks the living link

through Maillol with the Nabis, a short-lived group of 19th-century artists

inspired by Gauguin's Tahiti paintings that included Pierre Bonnard and Édouard

Vuillard as well as Maillol.

She was, besides, a remarkable

woman in her own right. Her attributes were perhaps best caught by Françoise

Gilot, not yet Picasso's partner, who met Vierny at Picasso's Paris studio in

1945. Maillol had died the previous year in a car accident, and yet Vierny had

blossomed. "Her bearing was regal," said Gilot. "More than a

muse, she was a priestess of art." As for Picasso, Gilot wrotes in

amusement: "He was deferential and attentive... as if beguiled by her

charm and mastery. If he had not been afraid of being pursued by Maillol's

ghost [Picasso was notably superstitious], he might have expressed his

admiration more openly." And Gilot said of herself: "I would have

loved to befriend Dina, but her triumphant femininity made me shy."

All of this goes some way to

explaining how this young, untutored immigrant model for a sculptor of nothing

but female nudes was able to tackle the legendary André Malraux, by 1965 De

Gaulle's minister of culture, and persuade him to take a gift of 18 of

Maillol's sculptures and put them on permanent display in the Tuileries - thus

fulfilling, in her role as an executor of Maillol's will, the sculptor's dying

wish.

Vierny was born in Chisinau, the

capital of Bessarabia (now Moldova). Her father knew Trotsky, but made no

attempt to hide his own social-democratic inclinations, and by 1925 it became

apparent that the new Russian hegemony was not good for their health. They fled

from Odessa in Ukraine and fetched up in Paris without a rouble in their

pockets. However, they survived, and Dina, a dutiful student, seemed destined

for a conventional career until Jean-Claude Dondel - later one of the four

architects of the Palais de Tokyo - met her and wrote to his friend Maillol,

saying that she was a walking Maillol sculpture. He persuaded her to visit

Maillol's Paris studio.

There was a double irony.

Firstly, Maillol's ideal was not a Jew from the Soviet Union, but the typical

peasant girl of Banyuls, his Catalan home town close to the border with Spain.

Secondly, the sculptor felt no need to acquire a model. In a journal entry,

Gide reported Maillol saying: "A model! A model! What the hell would I do

with a model? When I need to verify something, I go and find my wife in the

kitchen, I lift up her chemise, and I have the marble."

But Vierny's figure was a

revelation; broad hips, big thighs, high breasts. By 1934, when they met,

Maillol's career was running out of steam. All his work, whether war memorials,

monuments to heroes, allegorical figures for city centres, consisted almost

without exception of female nudes. The massive dignity of the calm,

Mediterranean classicism that came easily to Maillol, a reaction against the

vivid movement of Rodin's work, was beginning to bore the public. Vierny's

dynamic personality changed all this and inspired the approach that produced

The River, a figure with the usual Maillol characteristics - the fully rounded

and hollowed-out forms - but in vivid action, sprawling full length, Vierny's

wavy hair a metaphor for the running water.

During the second world war,

Vierny helped European intellectuals, including a son of Thomas Mann, to avoid

the Nazis by escaping to Spain along a rocky, tortuous path through the Pyrenees

shown to her by Maillol. She was arrested on suspicion and then sprung by a

lawyer paid by Maillol, whereupon she departed for Nice with letters of

introduction to Matisse and Bonnard, suggesting they should "borrow"

her.

She was only one of a bevy of

Matisse models, but the admiration between the artist and Vierny was mutual,

and although she had to remain still when she modelled for his drawings, he

allowed her to talk. By contrast, Bonnard, living at nearby Le Cannet,

instructed her to strip off but not to pose, and to forget that he was there.

"He didn't want me to keep still," said Vierny. "What he needed

was movement. He asked me to 'live' in front of him. He wanted both presence

and absence." Bonnard's 1941 painting Le Grand Nu Sombre was the fruit of

this association.

With Maillol, Bonnard and Matisse

all dead within a few years of the war's end, Vierny set up her own

well-regarded art gallery where, as well as her collection of modern, western

art and temporary shows, she exhibited the work of dissident Soviet artists.

But she continued to carry a torch for Maillol and established the Dina Vierny

Foundation, which led to the creation in 1995 of the Fondation Dina

Vierny-Musée Maillol in the left-bank rue de Grenelle. Maillol's former home in

the family vineyard above Banyuls is now another Maillol museum.

The two sons who survive her,

Olivier and Bertrand Lorquin, run the Paris museum, but Maillol's great

monument, the Tuileries gardens display, immortalises her as well.

• Dina Vierny, artist's model and

art dealer, born January 25, 1919; died January 21 2009

Betty Carter

Betty

Carter (born Lillie Mae Jones; May 19, 1929 – September 26, 1998) was an

American jazz singer known for her improvisational technique, scatting and

other complex musical abilities that demonstrated her vocal talent and

imaginative interpretation of lyrics and melodies. Vocalist Carmen McRae once

remarked: "There's really only one jazz singer—only one: Betty

Carter."

Carter

often recruited young accompanists for performances and recordings, insisting

that she "learned a lot from these young players, because they're raw and

they come up with things that I would never think about doing."

Betty

Carter is considered responsible for discovering great jazz talent, her

discoveries including John Hicks, Curtis Lundy, Mulgrew Miller, Cyrus Chestnut,

Dave Holland, Stephen Scott, Kenny Washington, Benny Green and more.

Utopia by Jongsook Kim

Jongsook

Kim, born in South Korea, received her BFA, MFA and PhD from Hongik University

in South Korea. Her works have been widely exhibited both nationally and

worldwide, and a part of them is housed in the permanent collections at the

Mogam Museum of Art and The Hoseo National Museum of Contemporary Art.

The

artist reinterprets traditional Korean ink-brush landscape paintings, giving it

a modern vocabulary by incorporating Swarovski crystals into it. Her father,

who ran a mother-of-pearl workshop, used traditional landscapes and motifs as

prototypes for the objects he made. This early memory influenced her to create

artworks of her own, onto which she incorporated the iridescence of Swarovski

crystals, combining it with Korean tradition.

The United States Capitol Building Ghosts

“One

soldier is known to have undergone excruciating pain one night during surgery

and he died on the operating table,” said Wallis. “So Capitol Police swear that

they hear moaning and see figures walking across the Capitol Rotunda, because

it was used as a makeshift hospital during the Civil War.” Rep. José Serrano (D-N.Y.)

“A

lot of Capitol Police swear they see and hear things, and it doesn’t surprise

me. The Capitol is a really old building. There’s been people who have been

shot in the building and it’s been a pretty violent place over history.” Anthony Wallis, research analyst, House

historian’s office.

“In

my old hideaway we had ghosts, we had a 300-pound table that we’d come in and

find in different parts of the room that we hadn’t left it in — it had moved

around by itself about every two or three months.” Sen. Patrick Leahy (D-Vt.)

The United States Capitol is

considered one of the most haunted buildings in Washington. The first

apparition to be seen there was in the 1860s as the Capitol was being

completed. Several spirits are said to haunt the Capitol due to tragedies

associated with its construction. One such ghost is said to be that of a worker

who died via a fall during the construction of the rotunda, and who now is

occasionally seen floating beneath the dome carrying a tray of woodworking

tools.

The Ghost of Henry Wilson

Henry Wilson of Massachusetts was

elected Vice President of the United States on the Republican ticket with

President Ulysses S. Grant. He was brought onto the ticket to replace the

ethically challenged Vice President Schuyler Colfax.

In 1873, Vice President Wilson suffered

a serious stroke but remained in office. Then, on November 10, 1875, he

suffered another attack that eventually killed him on November 22 a t7:00 AM

while he was working in the US Senate in the Capitol Building.

For years, some Capitol Police

have said that they have Wilson’s ghost walking from the old Senators tubs,

coughing and sneezing. Other say they have heard sneezes in the Senate hallways

when they are alone and still others say they have smelled the faint odor of

fresh soap near them accompanies by a cold chill.

The Voices in Statuary Hall

National Statuary Hall is said to

be haunted by a number of former members of Congress. Many politicians with

strong personalities and a powerful attachment to the institution of Congress

may continue to roam the halls of Congress long after their deaths.

Members of the United States

Capitol Police have claimed to have seen Senator (and from 1852 to 1854,

Representative) Thomas Hart Benton (above) sitting at a desk in National Statuary

Hall, although it has not been used as a legislative chamber since 1857.

Some claim that on the statues in

Statuary Hall dismount for their own inaugural ball from their places and dance

and that US Grant and Robert E. Lee have been seen meeting for a reconciliatory

handshake in the Hall.

The Curse of John Lenthall

In 1808 the buildings construction

superintendent John Lenthall disagreed with architect B. Henry Latrobe over the

Old Supreme Court Chamber. When Lenthall tried to remove braces from the

vaults, the ceiling collapsed and crushed him. In his last breath, legend goes,

Lenthall put a curse on the building.

The blue ghost of John Logan

Civil War general and Senator

John Logan is said to return to the old Military Affairs Committee room, with

the door to the room quietly opening and the general appearing, surrounded by a

blue haze. In the 1930s workmen discovered a sealed-up room containing what

many believed was Logan's stuffed horse.

A half hour after midnight on the first Tuesday after a full moon on the

stroke of the clock the door opens and the general appears in a “Sort of blue

haze” and stand there motionless

The Ghosts Joseph Cannon and Champ Clark

The spirits of Representative

Joseph Cannon (above) (R-Ill. and Speaker from 1903 to 1911) and Rep. Champ

Clark (Below) (D-Mo. and Speaker from 1911 to 1919) are claimed to occasionally

return to the dark chamber of the House of Representatives after midnight and,

after a loud rap from a gavel, resume the strong, angry debates they once had

in life.

The ghost of Wilbur Mills

Steve Livengood, chief tour guide

for the United States Capitol Historical Society, says he has seen the ghost of

former Representative Wilbur Mills (D-Ark.) near Mills' former office late at

night. Mills, once one of the most powerful men in the world, was pushed from

office due to a sex scandal.

Pierre L'Enfant

Pierre Charles L'Enfant, although

not a politician, was a brevet Major during the American Revolutionary War who

served with George Washington at Valley Forge. In 1791, L'Enfant was appointed

architect and planner of the new city of Washington in the District of

Columbia. Although L'Enfant submitted

grandiose plans for the new capital city, his plans were never fully adopted

and President Washington dismissed him. L'Enfant spent much of the rest of his

life attempting to wrest a monetary payment from Congress, and he died in

poverty in 1825. Eyewitnesses, however, claim to

have seen the spirit of L'Enfant walking through the Capitol, head down,

murmuring to himself, with the plans for the capital city tucked under his arm.

William P. Taulbee

The Capitol has also been witness

to murder and death. Rep. William P. Taulbee had been a congressman from

Kentucky from 1884 to 1888.

Charles E. Kincaid, a journalist

for The Louisville Times, had accused Taulbee of adultery and involvement in a

Patent Office scandal, which had ruined Taulbee's political career.

On February 28, 1890, the

ex-congressman and the reporter ran into one another in the Capitol, and

Taulbee assaulted and embarrassed Kincaid by tweaking the much smaller man's

nose. Kincaid ran home, grabbed a

pistol, and when he encountered Taulbee on a marble staircase leading from the

House chamber down to the dining room, he shot him in the face just below

Taulbee's left eye. Taulbee died two weeks later, and

Kincaid was acquitted after claiming self-defense. The steps where Taulbee was

shot still contain the bloodstains. Journalists and others claim, however, that

whenever a reporter slips on these steps, Taulbee's ghost briefly appears.

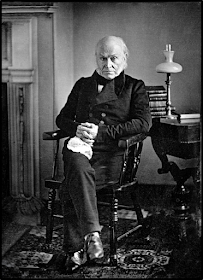

John Quincy Adams

Former President and then-Rep.

John Quincy Adams suffered a stroke at his desk in the House chamber on

February 21, 1848, and was taken into the Speaker's Room. His physical

condition was too precarious to move him, and he died at the Capitol two days

later.

Many people have claimed to have

heard Adams' ghost denouncing slavery late at night in National Statuary Hall,

and one Congressional staff member claims that by standing in the spot where

Adams' desk once stood a person can still hear the former president's ghostly

whisper.

James Garfield

James A. Garfield was a member of the House

from 1863 to 1881 before assuming the Presidency in March 1881. But Garfield

was shot by Charles J. Guiteau, a disgruntled office seeker, on July 2, 1881,

at 9:30 a.m. as he walked through the Sixth Street Station of the Baltimore and

Potomac Railroad in Washington, D.C.

Charles

J. Guiteau

Garfield died of heart failure brought about

by blood poisoning (itself caused by poor medical care) on September 19, 1881,

while recuperating at a beach home near Long Branch, New Jersey. Witnesses have

seen Garfield's ghost walking solemnly through the halls of Congress.

The Two Soldiers

The ghosts of at least two

soldiers are also said to haunt the Capitol. A few eyewitnesses have claimed

that whenever an individual lies in state in the Capitol Rotunda, a World War I

doughboy momentarily appears, salutes, then disappears.

A second apparition, which

eyewitnesses say is the ghost of an American Revolutionary War soldier, has

also appeared at the Washington Tomb.

According to several stories, the

soldier appears, moves around the Lincoln catafalque, and then passes out the

door into the hallway before disappearing.

The English Soldier

The Capitol building was burned

in 1814 by the British and some have seen a British soldier who runs the halls,

torch in hand.

The Stone Mason Ghast

Construction of the Capitol

building began after President George Washington and Secretary of State Thomas

Jefferson chose a winning design in 1792. The Capitol’s history of shootings

and fire apparently invited in some unseen visitors along the way. Legend tells

that during the construction of the Capitol building, an irritable carpenter

smashed the head of a stonemason and buried the body in a wall. The stonemason has

allegedly been spotted walking the halls.

The Black Cat

The legend of the Black Cat (AKA

the Demon Cat) is shared by the White House and Capitol Building, a few blocks

away.

At the White House, the Black Cat

is seen in the basement before various tragic events. But up in the Capitol, it apparently roams

the halls at will. It should be noted that back in the 19th century,

both buildings employed cats to check the rat population, which is numerous in

Washington.

Supposedly (No actual report

exists) A Capital Building Policeman (The Capital has its own police force, as

does the US Supreme Court and the local DC federally managed park system) said

he saw the cat in the very early 19th century and another was said

to have shot at it in 1862. “It seemed to grow” he said “as I looked at it.

When I shot at the critter, it jumped right over my head”

The cat sightings in both the

White House and Capitol Building tend to follow a national tragedy. A White House guard claimed to have seen just

before the Lincoln assassination, a week before the stock market crash of 1929

and also reportedly seen days before the assassination of JFK. The last semi-official

sighting of the Demon Cat was in 1940.

Interestingly enough, a few block

away from the White House sits the Octagon House, which is said to be curse and

haunted.

Legend says that Betty Taylor,

the married niece of the first owner of the house, tripped and fell to her

death by a black cat as she raced down the houses circular stairs. She was

running in the dark to greet her lover who entered the property by a secret

passage that opened on the bank of the Potomac (The river has since been pushed

by, but at one time it did run close to the house)

The Dopey Benny Gang

Benjamin Fein AKA Dopey Benny (Born

1887. Died 1962. ) Lived at 531 Montague

Street in Brooklyn. He was married with three children. The son of a tailor,

his nickname came from an adenoidal condition, which gave him a sleepy look.

When asked to explain the name, Fein said “I don’t know, I never used dope. I

got the title as a nickname years ago” As a teen, he was pickpocket and petty

thief.

Developing an arrest record in

1905 as head of a local street gang. He

served time in prison for armed robbery and was arrested twice for murder but

was never convicted on those charges.

In

1910, he joined Big Jake Zelig’s (Above. Zelig’s real name was either William Alberts

or Harry Morris) gang where he was essentially a strong-arm enforcer and labor

extortionist in the garment district with its predominately-Jewish immigrant

labor force.

When Zelig was killed, Benny struck off on his

own with the garment extortion business and had a long running battles and

feuds Italian labor racketeer Joe Sirroco and Joseph ‘The Greaser’ Rosenzweig

over territory. In 1913, with Jake Zelig dead, Fein tried to break the Romanian

born (1891) Rosenzweig’s iron grip on the garment industry in an uprising known

as the Labor Sluggers War that lasted from about 1913 until 1916.

At the

start of the war, on August 10, 1913, according to Fein, a patrolman named

Patrick Sheridan found him on the Forsyth and Grand (Fein lived at 102 Forsyth

Street) and said, “Come with me Benny”. And they walked to the corner of

Forsyth and Bowery where another foot cop was waiting.

At that point, the two cops took out

blackjacks and in front of 15 witnesses beat Fein and then arrested him for

assaulting an officer. Sheridan claimed that had ordered Fein and his gang to

disperse from the front of bathhouse and they refused and attacked him. A jury

agreed with Sheridan and found Fein guilty of second-degree assault.

Benny proclaimed his innocence and said that for an entire year, the

word on the street was that he would be framed for a crime so that he could be

taken off the streets “I have tried my best to be a good boy and avoid trouble”

he told judge “but the police would not have it that way. I am not without a

heart. I am human”

The judge sentenced him to five years at

Sing-Sing prison. On January 25, 1914, minutes after Benny was placed on a

train to Sing-Sing, his father, Issac came to the Tombs and asked to see his

son. When he was told that Benny had just left, the father burst into tears. On

May 13, 1914, the conviction was overturned by a high court.

In 1914, he was arrested for trying to extort

$500 from a business agent of the Local 509 Butchers Union named Ben

Solomonowitz. Fein had threatened to kill Solomonowitz if the official didn’t

have the money on Benny’s next visit, so Solomonowitz went to the police. The

following week, Fein returned and issues his threat, not realizing that

detectives were listening from the next room.

Fein was arrested and tossed in the Tombs with

bail set at $8,000, an enormous amount of money at the time. Fein waited in his cell for two days,

expecting he would be bailed out by his gang members or his friends in Tammany

Hall, but nothing happened. Certain that he had been sold out to the law, Fein

contacted the District Attorney and started to name names. In all, his

testimony was eighty pages long, detailing every possible aspect of labor

extortion within the garment industry in Manhattan including the history of

Monk Eastman and Big Jake Zelig and how Fein had come to declare war on Rosenzweig

He told the police “My first job as a gangster

for hire was to go to a shop and beat up some workmen there. The man that

employed me, a union official paid me $100 for my work and $10 for each of the

men that I hired. I planned the job and then told my employer that it would

take more men then he figured, and I would not touch it for under $600.00. He

agreed. I got my men together, divided them into squads and passed out pieces

of gas pipe and clubs to them. We met the workmen we were after as they came

from work and we beat them up. I didn’t want to mix up in the work myself and

kept out of it, but I was where I could watch my men work. The man who employed

me said he liked the work fine and paid me $500 as a bonus. That started me at

my work.”

Fein said he charged the unions

$150 to wreck a small manufacturers shop while large shops went up to $600.

Cutting off an ear or shooting an owner in the leg went for $60 to $100

depending on who the victim was. Throwing a manager down an elevator shaft was

$200. and that he earned more than $10,000 a year as an extortionist. He was

twice offered $15,000 in cash to go to work for the bosses instead of the workers,

but Fein turned them down twice. “I was for the working people” he told the DA.

He said he hired strong-arm women

as well as men, and paid them $7.50a day, decent money at the time. (The

average worked earned $19.23 a day at the time) It was also the same amount

that he paid his men. The women were armed with weighted umbrellas and long,

deadly sharp, hairpins.

When a theater on the east side

of New York hired non-union actors, Fein sent in women who feigned fits in the

middle of the performance. Usually six to ten women would suffer screaming and

fainting fits every twenty minutes until the performance was called off. Fein held trails for those accused of

breaking union laws. The accused were invited to attend to defend themselves.

If they were found guilty, Fein decided on the punishment. Among those he found

guilty included Herman Lieberwitz, a member of the garment workers union who

was moonlighting in upstate New York in nun-union jobs.

On August 10, 1910, Benny tracked

him down to 85 East Fourth Street and cracked his skull open. Lieberwitz died at Bellevue Hospital a short

time later. Next they beat Benjamin

Polar, a union leader who was, as Fein said, “in the way of some other union

people” Then Max Fleischer, a union organizer who had offended some workers,

was beaten nearly to death in a restaurant at 106 Delancey Street. A beer

bottle was broken over his head. They left a written notice on his body that he

was to retire from the union business.

Benny and his men destroyed shops

at 77 Green street that belonged to Max and Joseph Lampert because they refused

to pay a union fine of less than $100.00

Shops belonging to Max Roth at 1115 Broadway and another shop belonging

to Ron Kushin at 41 East Twenty-First Street, were destroyed.

Rather than kill witnesses, Fein offered them

a chance to relocate to Cleveland Ohio. His men all carried guns but were

seldom arrested for possession of a deadly weapon since the gangster were

accompanied by their girlfriends or prostitutes on each adventure where guns

were needed. When the police arrived, they slipped the guns into the women’s

backsides

Fein kept a diary of his life as

a union goon, a dairy that included names, dates, times and places. Based on

those notes, the DA issued 32 indictments against hoodlums and labor officials,

but none of them resulted in convictions. Benny was released without charges on

May 15, 1915.

November 28, 1914, during a clash

between union and non-union help at the S. Feldman Hat Factory at 168 Green

Street, a non-union enforcer named Max Green (146 East Houston) who worked

for Joe Sirroco was shot to death after

he shot Hyman Emmanuel, one of Benny’s men, in the leg. Waxy Gordon was later

identified as the man who killed Max Green.

On December 12, 1914, some men

from Benny’s gang were inside Madison Square Garden watching a bicycle race

when they were surrounded by members of

Joe Sirroco’s gang who challenged them to a fight. Outnumbered, Fein’s

men refused but at some point, Anthony Scantuli AKA Tony the Cheese (165 Hester

Street) one of Sirroco’s men was shot in the hip.

Tony Ross and Frank ”Nigger” Jula were

arrested for the shooting. Later, another fight broke out in front of the

London Theater near Broadway. Looking

for revenge for the attack at Madison Square Garden, Benny and his gang came to

Arlington Hall at 12-23 St. Mark’s Place in Manhattan where the Sirroco gang

was having an annual ball.

They waited outside the hall and when they saw

Charles Piazza, who worked for Joe Sirroco, walking down the street, they shot

him through the left shoulder and then returned to party they were having a few

blocks away. One bullet went wild and killed

a bystander named Frederick Strauss, a clerk of the court in

Manhattan. A witness identified Dopey Benny and his gang members

Little Abbie Beckerman (Born 1888 of 232 East Broadway) and Rubin Kaplan (Born

1888 of 226 Second Avenue) as the shooters. He also identified Waxy Gordon, (25

Delancey Street) and a member of Dopey Benny’s gang as another shooter. Another

witness said he saw a man he later identified as Gordon run up to the halls

bouncer, a character named Edward Morris AKA

Fat Bull and cry out “Fat Bull! Hide me!”

In the end, they were all

released due to lack of evidence. With the end of the Sluggers war and his

reputation in tatters, Benny’s power and influence waned. In November of 1925,

Fein was arrested in case that involved cocaine.

On May 29, 1915, Joseph ‘The Greaser’

Rosenzweig, a tailor’s presser by trade, pled guilty murder of Phillip Pinchy

Paul in 1914. he allowed a gangster named Benny Snyder to murder Paul because

Rosenzweig wanted Paul’s job as an organizer in the Furriers union.

On June 30, 1931, Benny, now 44 years old and

out of trouble for almost 14 years, was arrested on assault charges with

gangsters Samuel Hirsch and Samuel Rubin after throwing acid on local Brooklyn

businessman Mortimer Kahn as he sat in front of his neck tie shop at 124 Allen

street in Brooklyn.

Fein 1935

On February 25, 1942 he was sentenced to ten to

twenty years for trying to fence $250,000 in stolen property, taken mostly from

the garment center in Manhattan. Abe

Niggy Cohen, an old timer from the Lower East Side was convicted with him.

After his release from Sing-Sing, Fein settled down and went to work as tailor.

He died in 1962, from cancer and emphysema.

Fein 1942