On 22 January 1879, 150 British

troops fought 4,000 Zulu warriors at Rorke’s Drift. To Victorian readers, the

stand became one of the supreme symbols of imperial heroism, though Dominic

Sandbook explains how the battle is still clad in the myths of empire…

This article first appeared in the

January 2012 issue of BBC History Magazine

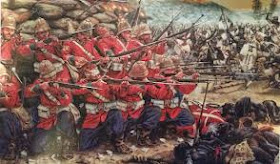

Alphonse de Neuville’s 1880 painting

The Defence of Rorke’s Drift.

Shortly before four o’clock in the

sweltering hot afternoon of 22 January 1879, a small group of British and

colonial troops, packed into a mission station on the border of Natal and the

Zulu Kingdom, had the news they dreaded. Earlier that day, a British column,

advancing into Zululand, had been annihilated at Isandlwana. Now there was

nothing between the enraged Zulus and the little mission station at Rorke’s

Drift, which had been turned into a makeshift hospital for the purposes of the

war.

Some officers wanted to pull out and

ride for safety, but Assistant Commissary James Dalton argued that they were

bound to be slowed down by the wagons of sick and wounded, which meant the

Zulus would inevitably overtake and destroy them. Instead, Dalton told his men

to put up makeshift barricades of biscuit boxes and corn sacks. “Now,” he said

grimly, “we must make a defence”.

So they waited. And at last, as the

first specks appeared on the horizon, one of the look-outs yelled the famous

words: “Here they come, black as hell and thick as grass!”

To modern ears the line may sound shocking, reminding

us that the British were, after all, invaders. To the men at

Rorke’s Drift, however, those words must have sounded terrifying. Barely 150

British and colonial troops, many of them frightened and exhausted, were packed

into the mission station, their red uniforms stained with dust and sweat.

Surrounding them were an estimated 4,000 Zulu warriors, many armed with rifles

as well as their short, lethal assegais. Rarely had any British force found

itself up against such overwhelming odds.

What happened next became one of the

most celebrated struggles in the history of the empire. All night the battle

raged, much of it concentrated around the low hospital building. Time and again

the Zulus charged, repelled only by volleys of lethal rifle fire and bloody

bayonet work.

“Such a heavy fire was sent along

the front of the hospital that, although scores of Zulus jumped over the mealie

bags to get into the building, nearly every man perished in that fatal leap,”

recalled one British defender. Another, Colour Sergeant Bourne, could not

disguise his admiration for his opponents’ courage. “To show their fearlessness

and their contempt for the redcoats,” he recalled, the Zulus “tried to leap the

parapet, and at times seized our bayonets, only to be shot down. Looking back,

one cannot but admire their fanatical bravery.”

Slowly but surely, weight of numbers

began to tell. Room by room the attackers advanced through the hospital, the

British desperately pulling back, dragging terrified patients with them. At one

stage the defenders were forced to hold off the Zulus through a narrow door,

while Privates John Williams and Henry Hook earned Victoria Crosses for their

bravery in saving eight patients under fierce Zulu fire.

By ten o’clock that night the

hospital and the cattle kraal had been abandoned, and the defenders were packed

into

a little bastion around the

storehouse. The British had fought for ten hours; most were wounded. But by now

the Zulus were themselves losing heart – and they were running out of

ammunition.

At two in the morning their attacks

began to slacken; by

four

o’clock, even the volleys of gunfire were dying down. And when dawn broke at

last, the British were astonished to see that the Zulus had gone. They left the

field littered with their dead and wounded. All in all, they had lost at least

350 men, to the defenders’ 17.

Rorke’s Drift became one of the

supreme symbols of imperial heroism. To Victorian readers, the image of a

handful of plucky British troops holding off thousands of Zulus was an

inspirational lesson in courage and self-sacrifice. Some 50,000 Londoners

bought tickets to see Alphonse de Neuville’s giant canvas 'The Defence of

Rorke’s Drift' (pictured), while Queen Victoria paid a large sum for Lady

Butler’s painting on the same theme.

Above all, the battle was

immortalised in the classic film Zulu (1964), starring Stanley Baker and

Michael Caine. As so often, the film played fast and loose with the facts: the

British never sang 'Men of Harlech'; the Zulus never saluted them with a song

praising their bravery; and the film fails to show the British executing Zulu

prisoners after the battle. Almost a century on, the myths of empire died hard.

Dominic Sandbrook’s is the author of is State of

Emergency: The Way We Were: Britain, 1970–1974 (Allen Lane). He is a frequent

guest on Radio 4’s Saturday Review.