DON’T WORRY-BE HAPPY

HERE'S SOME NICE ART FOR YOU TO LOOK AT....ENJOY!

Moonlit Landscape with a View of the New Amstel River and Castle Kostverloren (1647)

Moonlit Night, Franz Skarbina

MUSIC FOR THE SOUL

AND NOW, A BEATLES BREAK

TODAY'S ALLEGED MOB GUY

Robert Sasso , alleged Gambino Family Member

Robert Sasso is an alleged

Gambino crime family associate as was his father who did time for gun

trafficking. Sasso’s grandfather, named Robert as well, was President of Local

282 of the International Brotherhood of Teamsters and was also heavily

connected to the Gambinos. According to information provided by former Gambino

underboss Salvatore “Sammy the Bull” Gravano Sasso “gave sweetheart contracts

to mob-controlled companies and that he shared in payoffs to mobsters made by

contractors for labor peace.”

Sasso was forced to step down as

President and was later convicted of union racketeering. He spent several years

in prison until his release in 1997. That same year, his son was also released

from prison.

Last year Gambino allegedly shot

a 39-year-old man four times on a Whitestone shoreline near Boulevard St. in

Queens. CBS News reported that, “the victim was taken out to a jetty, where he

was shot. He was then able to call 911 and identify his shooter.” (Photo above

shows crime scene.)

WHY THE WORLD NEEDS EDITORS.....................

Photographs I’ve taken

The Observation and Appreciation of Architecture

ALBUM ART

Be happy, be around the people who get you.

THE CHILDREN'S CENTER

I was lucky enough to tour the Hamden (Connecticut) Children's Center where I lived in the summer of 1962

IT'S ALL GREEK MYTHOLOGY TO ME

The cornucopia has its roots in Greek

mythology. What we generally see depicted today as a woven horn overflowing

with flowers, fruits, nuts, grains, and all manner of wholesome symbols of

domestic wealth, began as an animal horn. According to the ancient Greeks, the horn of

plenty, as the cornucopia was originally known, was broken off the head of an

enchanted she-goat by Zeus himself when the infant Zeus was hidden away from

his father, the titan Cronos, in a cave on the isle of Crete.

While in hiding, Zeus

was fed and cared for by Amalthea, a figure alternately depicted as a naiad (water

nymph) or she-goat. Whether Amalthea was the goat herself, or just its

caretaker, most of the myths agree that Zeus, while suckling at the teat of a

magic goat, broke off its horn, which began to pour forth a never-ending supply

of nourishment. Thus the symbol of the horn of plenty was born.

THE ART OF WAR...............................

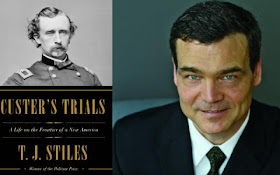

BOOK REVIEW

Custer Was Colorful and Eccentric but

Very Much a Man of His Time

By Kevin M. Levin

In a new biography, historian T.J.

Stiles portrays Custer in the context of his time, and the man who emerges is

much more than merely a martyr or a fool.

My favorite ice cream parlor growing up

on the South Jersey shore was called “Custard’s Last Stand,” whose logo

featured a cartoonish George Armstrong Custer brandishing two pistols in the

heat of battle and wearing a cowboy hat with two arrows shot through the crown.

Ice cream was likely the last thing on Custer’s mind at the Battle of Little

Bighorn on June 26, 1876, but for anyone enjoying a cone on a hot summer

evening with even a cursory understanding of American history the reference was

unmistakable even if the details were cloudy. “Custer’s Last Stand” is now more

a part of popular culture than history, which is little more than shorthand for

military recklessness, genocide against Native Americans, and the closing of

the frontier. While Custer and his 7th Cavalry Regiment will be forever

remembered as woefully surrounded by Lakota, Northern Cheyenne, and Arapaho

Indians, no one is quite sure how he ended up there.

In his new biography, Custer’s Trials:

A Life on the Frontier of a New America, Pulitzer Prize and National Book Award

winning author T.J. Stiles set out to explore Custer’s life not as a string of

events that led inevitably to the Little Bighorn River, but within the context

of mid-19th century America—a historical landscape defined by civil war,

westward expansion, the emancipation of four million people, expansive federal

government, and the explosion of an industrial market economy. This is not the

first biography of Custer, but it likely goes furthest in exploring his

contribution to Union victory during the Civil War and the difficulties he

faced adjusting to the world that he helped to create.

Readers are introduced to Custer fully

formed as a raucous and rebellious young West Point cadet in the middle of the

first of two court-martials for misconduct before joining his classmates and

the rest of the nation at war in 1861. Stiles fills in details about Custer’s

personal past and Democratic politics, which pushes the story forward with an

air of urgency. Custer wasted little time in finding a place on General George

McClellan’s staff and proving his battlefield prowess and worthiness of

command. At the young age of 23 he was promoted to the rank of brigadier

general and given command of four regiments of volunteer cavalry from his

adopted home state, Michigan. He distinguished himself in many of the major

campaigns of the Eastern Theater, including Gettysburg, the Overland Campaign,

and at Appomattox Court House, where Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia

was finally brought to bay. Along the way he cultivated the necessary political

support in Washington among Republican patrons, who remained suspicious of

Custer’s close personal ties with McClellan and his well-known Democratic

leanings.

Custer’s theatrics on the battlefield

may have earned him respect within the army and a reputation second to none in

the Northern press, but according to Stiles his romantic view of warfare and

search for glory was quickly being overshadowed by “industrialized slaughter.”

Custer, according to Stiles was “a living contradiction at the dawn of modern

warfare.” This is an overstatement. Certainly the role of cavalry was in

transition at this time and technological changes affected the scale of death

on the battlefield, but Custer was no more out of place in the Civil War than a

young Teddy Roosevelt was during the Spanish-American War a few decades later

charging up San Juan Hill with his Rough Riders.

One of the strengths of this book is

Stiles’s ability to connect Custer to broader questions faced by the nation at

the close of the war. All too often the fight over the western territories that

preceded the Civil War is disconnected from the political battles of

Reconstruction and the Indian Wars, which followed. Custer celebrated the

preservation of the Union and even the abolition of slavery, but like most

Americans he failed to move beyond deeply entrenched racial prejudices even in

light of his close interaction with Eliza Brown, a former slave, who cooked for

Custer in camp for a number of years. Custer’s contribution to Union victory

proved decisive for continued western expansion and a fulfillment of the

nation’s “Manifest Destiny” by white men and free labor.

Custer may have emerged from the Civil

War physically unharmed and as a national hero, but according to Stiles the

“Boy General”—now a lieutenant colonel in the Regular army—harbored

insecurities owing to limited opportunities for advancement in the military.

His foray into national politics during Reconstruction, investment in a failed

silver mine, and gambling on the stock market led nowhere and increasingly

strained his marriage to Libby Bacon. Stiles explains these setbacks as

evidence of the “contradiction” or tension between Custer the Romantic cavalier

and an increasingly industrial and urbanized society and impersonal political

bureaucracy. To whatever extent such a framework explains Custer’s

difficulties, it is clear that the timing of his graduation from West Point at

the beginning of the war and his temperament prepared him for little else.

Custer embraced his command assignment

with the 7th Cavalry on the Western Plains as an opportunity to re-build his

national reputation on the only stage on which he knew how to perform. He fashioned

himself as an expert on Indian military tactics, which was reinforced on more

than one battlefield. According to Stiles, the attention to a wardrobe of

buckskins and stories of buffalo hunts and other frontier adventures published

in leading newspapers returned Custer to iconic status within the military.

The challenge for any historian of the

Indian Wars is to place the actions of the United State military and Custer in

particular in proper context. It is here that Stiles’s earlier efforts to bridge

the Civil War, Reconstruction, and western expansion pays off. Reports of

atrocities—including surprise attacks on villages—clouded his reputation, but

Stiles shows that Custer’s racial outlook was perfectly consistent with the

overarching racial views of white Northerners and Southerners and those he

expressed publicly during Reconstruction. The United States was a white man’s

nation. Ultimately, as Stiles writes, “The very existence of the United States

was predicated on the dispossession of the indigenous. If Custer was wrong,

ultimately it was because the nation was wrong.”

Some readers will be disappointed that

Stiles relegates Custer’s famous last stand at the Little Bighorn to fifteen

pages in an epilogue. There are certainly plenty of detailed military studies

that explore the famous battle, but given Stiles’s overall goal with this

biography the decision makes perfect sense. It steers the reader clear of

engaging in tired debates about whether Custer got what he deserved. More

importantly, by detaching the battle from the main narrative Stiles punctuates

a point made early in the book: Custer’s life ought not to be overshadowed by

an event that long ago left the domain of history for legend.

Beat

poetry evolved during the 1940s in both New York City and on the west coast,

although San Francisco became the heart of the movement in the early 1950s. The

end of World War II left poets like Allen Ginsberg, Gary Snyder, Lawrence

Ferlinghetti and Gregory Corso questioning mainstream politics and

culture. A Brief Guide to the Beat Poets | Academy of American Poets https://www.poets.org/poetsorg

Happy. Just in my swim shorts,

barefooted, wild-haired, in the red fire dark, singing, swigging wine,

spitting, jumping, running — that’s the way to live. All alone and free in the

soft sands of the beach by the sigh of the sea out there, with the Ma-Wink fallopian

virgin warm stars reflecting on the outer channel fluid belly waters. And if

your cans are red hot and you can’t hold them in your hands, just use good old

railroad gloves, that’s all. Jack Kerouac

CHECK OUT PLUTO THE POP-ART STAR

OF THE WEEK

Check out Pluto the pop-art star

of the week in this recently NASA image. If not for the credits, we might have

well thought it is an artistic interpretation of the planet’s most intricate

features.

Of course, it is New Horizons

that managed to bring out the most colorful and spectacular image of Pluto we

have yet to see. It is a false color image. Nonetheless, it holds great

scientific value as the technique dubbed principal component analysis renders

the true variations in color among the different surface features of Pluto.

New Horizons captured the image

on July 14th. However, it was only released for the public following the

American Astronomical Society meeting on November 9th, where it was presented

in premiere.

According to the NASA website,

the image has been captured with New Horizons’ Ralph/MVIC color camera. The

distance is 22,000 miles.

Since the historic flyby of New

Horizons, few details were known about Pluto. Ever since, we have become

familiar to most of the features on the planet’s surface, its chemical

composition and Pluto’s atmosphere. In an effort to bring science closer to us,

NASA has translated complex scientific language in fascinating details on one

of the most interesting missions conducted.

Following a short pause, new data

collections are still beamed back from New Horizons. Thus, a whole new array of

information on the once frozen world will be made available to the public.

The hues in this image are

relevant for distinguishing between different Pluto surface features. So while

you check out Pluto the pop-art star of the week, remember the different

regions named just a couple of months ago.

To the north, Pioneer Terra looms

large with its craters marking the region. The canyons as well as plains of the

planet are also visibly marked. In the by now notorious heart-shaped region

titled Tombaugh Regio, the icy Sputnik Planum catches the eye. In the east, the

Tartarus Dorsa reveals the snakeskin pattern of the surface.

As New Horizons is venturing

further into the Kuiper Belt, more data and astonishing images on other objects

are bound to become fascinating topics soon. Nonetheless, we can safely assume

that we’re not done with Pluto yet.

Photo Credits: nasa.gov

Understanding why Shakespeare

made his tortured, tragic hero a Moor.

By Isaac Butler

Is Othello black? With the news

that David Oyelowo will play Othello opposite Daniel Craig’s Iago and that the

Metropolitan Opera is finally discontinuingthe practice of blackface in

productions of Otello, we may see a revival of thisoft-asked question. What people

mean when they ask if Othello is black is: What did Shakespeare mean when he

called Othello black? Would we say Othello is black today?

It’s an understandable question.

Shakespeare’s writing mostly predates the transatlantic slave trade and the

more modern obsession with biological classification, both of which gave rise

to our contemporary ideas of race. When Shakespeare used the word “black” he

was not exactly describing a race the way we would. He meant instead someone

with darker skin than an Englishman at a time when Englishmen were very, very

pale. Although Othello is a Moor, and

although we often assume he is from Africa, he never names his birthplace in

the play. In Shakespeare’s time, Moors could be from Africa, but they could

also be from the Middle East, or even Spain.

While the question is logical to

me, as a reader, a director, and a lover of Shakespeare, it’s not the most

interesting one. As language’s meaning evolves, so do these plays, even if

their words remain exactly the same. To us today, the word “black” carries with

it a specific cluster of associations informed by history, culture,

stereotypes, and literature. Othello may have started in conversation with

Shakespeare’s definition of blackness, but today, he speaks with ours.

A much more interesting question,

really, is: Why is Othello black? Why did Shakespeare write a domestic tragedy

about jealousy, and make the husband a Moor? Is Othello’s race a canard, or is

it the key to unlocking the play’s deeper meanings?

Would you believe the answer to

all of this might involve pirates?

Before we hoist the Jolly Roger,

we should consider more practical explanations for Shakespeare’s choice. In

August of 1600, the ambassador of the King of Barbary—roughly, modern-day

Morocco—came to London as the guest of Queen Elizabeth for a six-month

residency at court. He was a celebrity, Katie Sisneros, a Ph.D. candidate at

the University of Minnesota focusing on representations of Turks in English

popular literature, told me in an interview. “He would’ve had some sort of

public parade. People who had never seen a Muslim, never seen a Moor, they

probably saw their first Moor during that visit.” Something of the ambassador’s

charisma and dashing good looks remain in this portrait of him painted in

England at the time.

We know from records that

Shakespeare’s company performed at court while the ambassador—his full name was

Abd el-Ouahed ben Messaoud ben Mohammed Anoun—was there, which means that

Shakespeare may very well have acted in a play in front of him. (Of course it’s

just as likely that one or both men had a cold and missed the show; that’s how

nebulous Shakespeare scholarship can get.) Shakespeare likely began writing

Othello the next year, and performed it for the first time in 1604.

Moors were so hot right nowback

then.

If we remember that Shakespeare

was a human being and a good businessman, we get the most obvious answer to our

question. The Bard had just met and performed for a Moor who was a superstar.

England’s relationship to the Ottoman Empire and to Moors was a pressing issue.

Moors wereso hot right now back then. From there, we can imagine our inspired

playwright casting about for a story about a Moor—Shakespeare’s plots were

mostly unoriginal and adapted—and finding Giraldi Cinthio’s Hecatommithi, a

short story collection modeled on the Decameron. Shakespeare takes two cups of

Cinthio, mixes a few dashes of purloined “facts” about both Africa and Venice

from recently translated books and, in a couple of years, he’s baked a play.

Unfortunately for Shakespeare, in

between Abd Anoun’s visit and Othello’s premiere, Queen Elizabeth died. King

James had a much frostier relationship with the Ottomans than his predecessor

did. “James tried to roll back the diplomatic advances that Elizabeth made,” Sisneros

said. “He starts using ‘let’s have a new crusade’ language.”

Sisneros told me that to much of

Shakespeare’s audience, “all Moors were Turks, even though not all Turks were

Moors.” Furthermore, while calling someone a Moor meant that they had dark skin,

in the early 17th century, the term carried a religious meaning as well. “There

was no word for Muslim at the time. They used Turk,Mosselman, Mohammedan, these

are all synonyms.”

Othello, then, may have appeared

at the time as an ex-Muslim—he mentions his baptism within the play—who slowly

reverts to behavior that is more stereotypically “Muslim.” The Tragedy of

Othello, the Moor of Venice could be read as a nightmare about the

impossibility of conversion and assimilation, meanings within the play that are

less visible to us because we lack the original audience’s context.

This is where piracy becomes

important. If you were a British sailor working a trading ship at the time, you

ran a real risk of being sacked by pirates, often Turks. If this happened, you

were ransomed or, if no ransom was forthcoming, enslaved. Often, you would be

offered your freedom if you converted to Islam, a process called turning

Turk. To sweeten the deal, you could be

promised land, a job, or even a wife. “If an English person is kidnapped, sold

into slavery, converts for their freedom, returns to England—and this happened

a lot—could they convert back?” asked Sisneros. “And if so, how could that

conversion be trusted? It’s an extremely troubling question at the time.”

Othello even uses this anxiety when breaking up a fight between his men, asking

them, “Are we turned Turks? And to ourselves do that/ Which heaven hath forbid

the Ottomites?”

Similarly, many English feared

that Muslim converts to Christianity were incapable of fully changing.

Othello’s blackness, then, worked for the play’s original audience as a symbol

of his “true” essence. Iago scrapes away the veneer of manners Othello has

layered over this, revealing what Shakespeare’s audience would’ve thought was

“real” all along. In the second half of the play, Othello begins having

seizures and wild mood swings, and his vocabulary gets simpler. Othello himself

echoes the idea that he’s “reverting” when he commits suicide, describing to

the assembled Venetians how he wants to be remembered:

And say besides that in Aleppo

once,

Where a malignant and a turbaned

Turk

Beat a Venetian and traduced the

state,

I took by th’ throat the

circumsized dog

And smote him—thus! Stabs Himself

Othello could be talking about

Desdemona as the abused Venetian or, according to Sisneros, “he could be even

referring to himself. He killed the good part of himself, thus ‘traducing’ the

Venetian state.” Either way, it’s hard to escape the sense that Othello is

explicitly saying he has “turned Turk” by the end of the play.

It could also be that Othello’s

blackness provided Shakespeare a new way to explore questions that consumed his

playwriting at this time in his career: What is identity, and how is it formed?

What is a man? What is an Englishman?

To understand how Othello helped

Shakespeare tease out those questions, let’s first look at how Shakespeare used

references to blackness. There are many (largely negative) uses of the word

“black” throughout the play, and there are ways that characters reference

Othello’s blackness without using the word. Brabantio, Desdemona’s father,

enraged at his daughter’s elopement, accuses Othello, saying, “Damned as thou

art, thou hast enchanted her,” because she never would’ve consented to run “to

the sooty bosom/ of such a thing as thou.” “Sooty” refers to Othello’s skin

color but, importantly, “damned” does too. Devils in Shakespeare’s time were

thought to be black. Black skin was a sign of being a devil, capable of

witchcraft. Later, Iago promises to turn Desdemona’s reputation as black as

“pitch.”

Complexion in Shakespeare’s time

was a measurement of both beauty and virtue. According to Villanova Shakespeare

scholar John-Paul Spiro, to be “fair” was to be both pale and virtuous, not

synonymously, but simultaneously. Similarly, Spiro said, “if you look at the

poetry, Black-means-ugly is all over the place. The Dark Lady in the sonnets,

for example. Shakespeare can’t stop pointing out that she’s not supposed to be

attractive because she’s ‘dark.’ In Much Ado About Nothing, Claudio says he’ll

marry a woman he’s never met ‘tho she be an Ethiope,’ a word Shakespeare uses

in other plays to mean both black and ugly.”

Shakespeare was a product of his time, after all, and in his time men

were publishing texts like Stephen Batman’s The Doome Warning All Men to

Judgement, which describes “Ethiopes” as having “four eyes: and it is said that

in Eripia be found” men that “are long necked, and mouthed as a crane.”

Othello only uses the word

“black” to describe himself twice. Once, as he contemplates Desdemona’s

infidelity, he says that perhaps she has strayed because “I am black/ And have

not those soft parts of conversation/ That chamberers have.” Later, he says

that if she’s cheated on him, “Her name, that was as fresh/ As Dian's visage,

is now begrimed and black/ As mine own face.” His otherness, the “passing

strange” aspects that made him alluring to Desdemona, have now become ugly in

his eyes—because he believes they’ve become ugly in hers. His entire conception

of who he is has changed, paving the way for the murder of his new bride.

So does Othello treat Othello as

a monster or do the characters in Othello make him that way? To Spiro, the

unanswerability of the question is what makes it worth asking. “At this

time—remember he’s written Hamlet, Twelfth Night, and Measure for Measurenot

too long ago—Shakespeare is preoccupied with and invested in a deep skepticism about

the knowability of the world, the self, and the other. You are a mystery to

yourself; other people are a mystery to you. What is terrifying about Othello

is that the mystery deepens with intimacy.”

Spiro traces this thread in

Shakespeare’s writing to the Bard’s likely familiarity withMontaigne’s Essays,

which often double back on their own assumptions, and with the shifting

theological emphasis of Protestantism. “In Catholicism, to be a good person,

you have to go to confession and mass. Protestantism is now saying ‘No, you

must always doubt your intentions, you must always wonder if you did things for

the right reason.’ ” As a result, Shakespeare’s characters’ thoughts become a

swirling vortex of uncertainty. “Look at Brutus,” Spiro said. “Look at Hamlet.

The more you interrogate the self, the more incoherent and unknowable it gets.”

And Othello presented

Shakespeare’s audience with a kind of incoherence when he first walked onstage:

He did not fit any of his era’s stereotypes of how he should behave. At the

beginning of the play, Othello is straightforward, honest, and noble. He cannot

conceive of being lied to. He isn’t at all what an English audience would

expect. The Venetians around him, on the other hand, are exactly what the

audience would expect. They’re, venal, dishonest, passionate, and unfaithful.

Iago’s case against Desdemona rests in part on using these stereotypes as

proof. As he says to Othello, “In Venice [wives] do let heaven see the pranks/

They dare not show their husbands.”

“If Othello really is that

decent, honest, and credulous, if he can really have friends and be loved by a

beautiful woman, the white characters in the play can’t accept it,” Spiro said.

“Iago has to destroy him.”

Throughout his career,

Shakespeare was conflicted about identity at the moment when the question What

is an Englishman? was as vital to his audience as questions about identity are

to us today. “In Twelfth Night you have the idea that you could make someone

insane simply by telling him he’s insane,” Spiro said. “If Richard III had had

a straight back, would he be a good person?

Is his crooked back a sign that he is a bad person, or do we treat

people with crooked backs badly?” To Spiro, the terrifying note Shakespeare sounds

again and again, despite being a word-drunk pioneer of the English language, is

that talking about it doesn’t help. Hamlet can’t reason his way out of the trap

of the self. Neither can Othello, who is helped neither by logic, nor by proof,

nor friendship, nor even by language, because all of these normal ways of

making sense of the world have been arrayed in a conspiracy against him by

Iago.

All along, the play is asking

what makes a person, what is identity, and how belonging to an identity group

shapes who you are. These questions haunt us today, but they were important to

Shakespeare’s audience as well. Moors weren’t the only converts, after all. The

entire nation had recently “converted” to the Church of England. If, according

to your new faith your goodness is never guaranteed, and if all Iago needs is

two days to turn a noble convert and trusted military leader into a monster,

imagine what he could do if left alone with you.

Isaac Butler is a writer and

occasional theater director. He currently serves as the senior editor of the

Perception Institute.

GOOD WORDS

TO HAVE………………..

Solipsism (SOL-ip-siz-uhm) 1. The view or theory that the self is all that exists or can be known to exist.2. Self-absorption or self-centeredness.From Latin solus (alone) + ipse (self)

HERE'S PLEASANT POEM FOR YOU TO ENJOY................

MISH MOSH..........................................

Mish Mash: noun \ˈmish-ˌmash, -ˌmäsh\ A : hodgepodge, jumble “The painting was just a mishmash of colors and abstract shapes as far as we could tell”. Origin Middle English & Yiddish; Middle English mysse masche, perhaps reduplication of mash mash; Yiddish mish-mash, perhaps reduplication of mishn to mix. First Known Use: 15th century

Wanda

Hawley

In addition to enjoying swimming

and gold, Wanda was vocally trained and toured for a while across the country

singing opera. She was also an

accomplished pianist.

She was to be a grand opera prima

donna...and her mother had her put through a strict course of training vocally,

as well as at the piano. The result is

that she can sit down now and tick off a few Rachmaninoff preludes and Bach

fugues without winking an eye.

["Victuals and Voice", Photoplay, January 1920]

She is said to have appeared in

the 1925 version of The Wizard of Oz, though her role is uncredited and, as of

yet, unverified. At the height of her

career, she was receiving the same amount of fan mail as Gloria Swanson, and

starred with matinee idols like Rudolph Valentino and Wallace Reid. Though well-regarded, her career

faltered after sound came in (her IMDb lists only three credits, ending in

1932), and she is rumored to have become a call girl in San Francisco. She died in 1963.

Sculpture this and Sculpture that

“The Gates of Hell,” ( Modeled 1880-1917; cast 1926-1928, by Auguste Rodin

Budapest, Ervin Loranthh Herve

THE ART OF PULP

I LOVE BLACK AND WHITE PHOTOS FROM FILM

GREAT WRITING

"If people bring so much

courage to this world the world has to kill them to break them, so of course it

kills them. The world breaks every one and afterward many are strong at the broken

places. But those that will not break it kills. It kills the very good and the

very gentle and the very brave impartially. If you are none of these you can be

sure it will kill you too but there will be no special hurry."

"The coward dies a thousand

deaths, the brave but one'.... (The man who first said that) was probably a

coward.... He knew a great deal about cowards but nothing about the brave. The

brave dies perhaps two thousand deaths if he's intelligent. He simply doesn't

mention them."

"That night at the hotel, in

our room with the long empty hall outside and our shoes outside the door, a

thick carpet on the floor of the room, outside the windows the rain falling and

in the room light and pleasant and cheerful, then the light out and it exciting

with smooth sheets and the bed comfortable, feeling that we had come home,

feeling no longer alone, waking in the night to find the other one there, and

not gone away; all other things were unreal. We slept when we were tired and if

we woke the other one woke too so one was not alone. Often a man wishes to be

alone and a girl wishes to be alone too and if they love each other they are

jealous of that in each other, but I can truly say we never felt that. We could

feel alone when we were together, alone against the others ... But we were

never lonely and never afraid when we were together. I know that the night is

not the same as the day: that all things are different, that the things of the

night cannot be explained in the day, because they do not then exist, and the

night can be a dreadful time for lonely people once their loneliness has started.

But with Catherine there was almost no difference in the night except that it

was an even better time. If people bring so much courage to the world the world

has to kill them to break them, so of course it kills them. The world breaks

every one and afterward many are strong at the broken places. But those that

will not break it kills. It kills the very good and the very gentle and the

very brave impartially. If you are none of these you can be sure it will kill

you too but there will be no special hurry."

"Once in camp I put a log on

a fire and it was full of ants. As it commenced to burn, the ants swarmed out

and went first toward the center where the fire was; then turned back and ran

toward the end. When there were enough on the end they fell off into the fire.

Some got out, their bodies burnt and flattened, and went off not knowing where

they were going. But most of them went toward the fire and then back toward the

end and swarmed on the cool end and finally fell off into the fire. I remember

thinking at the time that it was the end of the world and a splendid chance to

be a messiah and lift the log off the fire and throw it out where the ants

could get off onto the ground. But I did not do anything but throw a tin cup of

water on the log, so that I would have the cup empty to put whiskey in before I

added water to it. I think the cup of water on the burning log only steamed the

ants."

No tears in the writer, no tears in the reader. No surprise in the writer, no surprise in the reader. Robert Frost

HERE'S MY LATEST BOOKS.....

This is a book of short stories taken from the things I saw and heard in my childhood in the factory town of Ansonia in southwestern Connecticut.

Most of these stories, or as true as I recall them because I witnessed these events many years ago through the eyes of child and are retold to you now with the pen and hindsight of an older man. The only exception is the story Beat Time which is based on the disappearance of Beat poet Lew Welch. Decades before I knew who Welch was, I was told that he had made his from California to New Haven, Connecticut, where was an alcoholic living in a mission. The notion fascinated me and I filed it away but never forgot it.

The collected stories are loosely modeled around Joyce’s novel, Dubliners (I also borrowed from the novels character and place names. Ivy Day, my character in “Local Orphan is Hero” is also the name of chapter in Dubliners, etc.) and like Joyce I wanted to write about my people, the people I knew as a child, the working class in small town America and I wanted to give a complete view of them as well. As a result the stories are about the divorced, Gays, black people, the working poor, the middle class, the lost and the found, the contented and the discontented.

Conversely many of the stories in this book are about starting life over again as a result of suicide (The Hanging Party, Small Town Tragedy, Beat Time) or from a near death experience (Anna Bell Lee and the Charge of the Light Brigade, A Brief Summer) and natural occurring death. (The Best Laid Plans, The Winter Years, Balanced and Serene)

With the exception of Jesus Loves Shaqunda, in each story there is a rebirth from the death. (Shaqunda is reported as having died of pneumonia in The Winter Years)

Sal, the desperate and depressed divorcee in Things Change, changes his life in Lunch Hour when asks the waitress for a date and she accepts. (Which we learn in Closing Time, the last story in the book) In The Arranged Time, Thisby is given the option of change and whether she takes it or, we don’t know. The death of Greta’s husband in A Matter of Time has led her to the diner and into the waiting arms of the outgoing and loveable Gabe.

Although the book is based on three sets of time (breakfast, lunch and dinner) and the diner is opened in the early morning and closed at night, time stands still inside the Diner. The hour on the big clock on the wall never changes time and much like my memories of that place, everything remains the same.

http://www.amazon.com/Short-Stories-Small-William-Tuohy/dp/1517270456/ref=sr_1_1?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1444164878&sr=1-1&keywords=short+stories+from+a+small+town

The Valley Lives/ Book Review

By Marion Marchetto, author of The Bridgewater Chronicles on October 15, 2015

Short Stores from a Small Town is set in The Valley (known to outsiders as The Lower Naugatuck Valley) in Connecticut. While the short stories are contemporary they provide insight into the timeless qualities of an Industrial Era community and the values and morals of the people who live there. Some are first or second generation Americans, some are transplants, yet each takes on the mantle of Valleyite and wears it proudly. It isn't easy for an author to take the reader on a journey down memory lane and involve the reader in the life stories of a group of seemingly unrelated characters. I say seemingly because by book's end the reader will realize that he/she has done more than meet a group of loosely related characters.

We meet all of the characters during a one-day time period as each of them finds their way to the Valley Diner on a rainy autumn day. From our first meeting with Angel, the educationally challenged man who opens and closes the diner, to our farewell for the day to the young waitress whose smile hides her despair we meet a cross section of the Valley population. Rich, poor, ambitious, and not so ambitious, each life proves that there is more to it beneath the surface. And the one thing that binds these lives together is The Valley itself. Not so much a place (or a memory) but an almost palpable living thing that becomes a part of its inhabitants.

Let me be the first the congratulate author John William Tuohy on a job well done. He has evoked the heart of The Valley and in doing so brought to life the fabric that Valleyites wear as a mantle of pride. While set in a specific region of the country, the stories that unfold within the pages of this slim volume are similar to those that live in many a small town from coast to coast.

An award winning full length play.

"Cyberdate.Com is the story of six ordinary people in search of romance, friendship and love and find it in very extraordinary ways. Based on the real life experiences of the authors misadventures with on line dating, Cyber date is a bittersweet story that will make you laugh, cry and want to fall in love again." Ellis McKay

Cyberdate.Com, was chosen for a public at the Actors Chapel in Manhattan in February of 2007 as part of the groups Reading Series for New York project. In June of 2008, the play won the Virginia Theater of The First Amendment Award for best new play. The play was also given a full reading at The Frederick Playhouse in Maryland in March of 2007.

No time to say goodbye

In

1962, six year old John Tuohy, his two brothers and two sisters entered

Connecticut’s foster care system and were promptly split apart. Over the next

ten years, John would live in more than ten foster homes, group homes and state

schools, from his native Waterbury to Ansonia, New Haven, West Haven, Deep

River and Hartford. In the end, a decade later, the state returned him to the

same home and the same parents they had taken him from. As tragic as is funny

compelling story will make you cry and laugh as you journey with this child to

overcome the obstacles of the foster care system and find his dreams.

http://www.amazon.com/No-Time-Say-Goodbye-Memoir/dp/0692361294/

http://amemoirofalifeinfostercare.blogspot.com/

http://www.amazon.com/No-Time-Say-Goodbye-Memoir/dp/

”

********************

SAMPLE

CHAPTER

Chapter One

To read the first 12

chapters of this book, visit it's BlogSpot @

amemoirofalifeinfostercare.blogspot.com/

Do you think, because I am poor, obscure, plain and little, I am soulless and heartless? You think wrong! - I have as much soul as you, - and full as much heart! ― Charlotte Brontë, Jane Eyre

I am here because I worked too hard and too long not to be here. But although I told the university that I would walk across the stage to take my diploma, I won't. At age fifty-seven, I'm too damned old, and I'd look ridiculous in this crowd. From where I'm standing in the back of the hall, I can see that I am at least two decades older than most of the parents of these kids in their black caps and gowns.

So I'll graduate with this class, but I won't walk across the stage and

collect my diploma with them; I'll have the school send it to my house. I only

want to hear my name called. I'll imagine what the rest would have been like.

When you've had a life like mine, you learn to do that, to imagine the good

things.

The ceremony is about to begin. It's a warm June day and a hallway of

glass doors leading to the parking lot are open, the dignitaries march onto the

stage, a janitor slams the doors shut, one after the other.

That banging sound.

It's Christmas Day 1961 and three Waterbury cops are throwing their bulk

against our sorely overmatched front door. They are wearing their long woolen

blue coats and white gloves and they swear at the cold.

They've finally come for us, in the dead of night, to take us away, just

as our mother said they would.

"They'll come and get you kids," she screamed at us, "and

put youse all in an orphanage where you'll get the beatin's youse deserve, and

there won't be no food either."

That's why we're terrified, that's why we don't open the door and that's

how I remember that night. I was six years old then, one month away from my

seventh birthday. My older brother, the perpetually-worried, white-haired

Paulie, was ten. He is my half-brother, actually, although I have never thought

of him that way. He was simply my brother. My youngest brother, Denny, was six;

Maura, the baby, was four; and Bridget, our auburn-haired leader, my half

-sister, was twelve.

We didn't know where our mother was. The welfare check, and thank God

for it, had arrived, so maybe she was at a gin mill downtown spending it all,

as she had done a few times before.

Maybe she'd met yet another guy, another

barfly, who wouldn't be able to remember our names because his beer-soaked

brain can't remember anything. We are thankful that he'll disappear after the

money runs out or the social worker lady comes around and tells him he has to

leave because the welfare won't pay for him as well as for us. It snowed that

day and after the snow had finished falling, the temperature dropped and the

winds started.

"Maybe she went to Brooklyn," Paulie said, as we walked

through the snow to the Salvation Army offices one that afternoon before the

cops came for us.

"She didn't go back to New York," Bridget snapped. "She

probably just--"

"She always says she gonna leave and go back home to

Brooklyn," I interrupted.

"Yeah," Denny chirped, mostly because he was determined to be

taken as our equal in all things, including this conversation.

We walked along in silence for a second, kicking the freshly fallen snow

from our paths, and then Paulie added what we were all thinking: "Maybe

they put her back in Saint Mary's."

No one answered him. Instead, we fell into our own thoughts, recalling

how, several times in the past, when too much of life came at our mother at

once, she broke down and lay in bed for weeks in a dark room, not speaking and

barely eating. It was a frightening and disturbing thing to watch.

"It don't matter," Bridget snapped again, more out of

exhaustion than anything else. She was always cranky. The weight of taking care

of us, and of being old well before her time, strained her. "It don't

matter," she mumbled.

It didn't matter that night either, that awful night, when the cops were

at the door and she wasn't there. We hadn't seen our mother for two days, and

after that night, we wouldn't see her for another two years.

When we returned home that day, the sun had gone down and it was dark

inside the house because we hadn't paid the light bill. We never paid the

bills, so the lights were almost always off and there was no heat because we

didn't pay that bill either. And now we needed the heat. We needed the heat

more than we needed the lights.

The cold winter winds pushed up

at us from the Atlantic Ocean and down on us from frigid Canada and battered

our part of northwestern Connecticut, shoving freezing drifts of snow against

the paper-thin walls of our ramshackle house and covering our windows in a

thick veneer of silver-colored ice.

The house was built around 1910 by the factories to house immigrant

workers mostly brought in from southern Italy. These mill houses weren't built

to last. They had no basements; only four windows, all in the front; and

paper-thin walls. Most of the construction was done with plywood and tarpaper.

The interiors were long and narrow and dark.

Bridget turned the gas oven on to keep us

warm. "Youse go get the big mattress and bring it in here by the

stove," she commanded us. Denny, Paulie, and I went to the bed that was in

the cramped living room and wrestled the stained and dark mattress, with some

effort, into the kitchen. Bridget covered Maura in as many shirts as she could

find, in a vain effort to stop the chills that racked her tiny and frail body

and caused her to shake.

We took great pains to position the hulking mattress in exactly the

right spot by the stove and then slid, fully dressed, under a pile of dirty

sheets, coats, and drapes that was our blanket. We squeezed close to fend off

the cold, the baby in the middle and the older kids at the ends.

"Move over, ya yutz, ya," Paulie would say to Denny and me

because half of his butt was hanging out onto the cold linoleum floor. We could

toss insults in Yiddish. We learned them from our mother, whose father was a

Jew and who grew up in a Jewish neighborhood in New York.

I assumed that those words we learned were standard American English, in

wide and constant use across our great land. It wasn't until I was in my

mid-twenties and moved from the Naugatuck Valley and Connecticut that I came to

understand that most Americans would never utter a sentence like, "You and

your fakakta plans".

We also spoke with the Waterbury aversion to the sound of the letter

"T," replacing it with the letter "D," meaning that

"them, there, those, and these" were pronounced "dem, dere,

dose, and dese." We were also practitioners of "youse," the

northern working-class equivalent to "you-all," as in "Are youse

leaving or are youse staying?"

"Move in, ya yutz, ya," Paulie said again with a laugh, but we

didn't move because the only place to move was to push Bridget off the

mattress, which we were not about to do because Bridget packed a wallop that

could probably put a grown man down. Then Paulie pushed us, and at the other

end of the mattress, Bridget pushed back with a laugh, and an exaggerated,

rear-ends pushing war for control of the mattress broke out.

From the Inside Flap

AMAZON

REVIEWS

By

jackiehon October 13, 2015

After reading about John's deeply

personal and painful past, I just wanted to hug the child within him......and

hug all the children who were thrown into the state's foster system....it is an

amazing read.......

By Jane Pogodaon October 9, 2015

I truly enjoyed reading his

memoir. I also grew up in Ansonia and had no idea conditions such as these

existed. The saving grace is knowing the author made it out and survived the

system. Just knowing he was able to have a family of his own made me happy. I

attended the same grammar school and was happy that his experience there was

not negative. I had a wonderful experience in that school. I wish that I could

have been there for him when he was at the school since we were there at

probably at the same time.

By Sueon September 27, 2015

Hi - just finished your novel

"No time to say goodbye" - what a powerful read!!! - I bought it for

my 90 year old mom who is an avid reader and lived in the valley all her

life-she loved it also along with my sister- we are all born and raised in the

valley- i.e. Derby and Ansonia

By David A. Wrighton September 7, 2015

I enjoyed this book. I grew up in

Ansonia CT and went to the Assumption School. Also reconized all the places he

was talking about and some of the families.

By Robert G Manleyon September 7, 2015

This is a wonderfully written

book. It is heart wrenchingly sad at times and the next minute hilariously

funny. I attribute that to the intelligence and wit of the author who combines

the humor and pathos of his Irish catholic background and horrendous

"foster kid" experience. He captures each character perfectly and the

reader can easily visualize the individuals the author has to deal with on

daily basis. Having lived part of my life in the parochial school system and

having lived as a child in the same neighborhood as the author, I was vividly brought

back to my childhood .Most importantly, it shows the strength of the soul and

how just a little compassion can be so important to a lost child.

By LNAon July 9, 2015

John Tuohy writes with compelling

honesty, and warmth. I grew up in Ansonia, CT myself, so it makes it even more

real. He brings me immediately back there with his narrative, while he wounds

my soul, as I realize I had no idea of the suffering of some of the children

around me. His story is a must read, of courage and great spirit in the face of

impoverishment, sorrow, and adult neglect. I could go on and on, but just get

the book. If you're like me, you'll soon be reading it out loud to any person

in the room who will listen. Many can suffer and overcome as they go through

it, but few can find the words that take us through the story. John is a gifted

writer to be able to do that.

By Barbara Pietruszkaon June 29, 2015

I am from Connecticut so I was

very familiar with many locations described in the book especially Ansonia

where I lived. I totally enjoyed the book and would like to know more about the

author. I recommend the book to everyone

By Joanne B.on June 28, 2015

What an emotional rollercoaster.

I laughed. I cried. Once you start reading it's hard to stop. I was torn

between wanting to gulp it up and read over and over each quote that started

the chapter. I couldn't help but feel part of the Tuohy clan. I wanted to

scream in their defense. It's truly hard to believe the challenges that foster

children face. I can only pray that this story may touch even one person facing

this life. It's an inspiring read. That will linger long after you finish it.

This is a wonderfully written memoir that immediately pulls you in to the lives

of the Tuohy family.

By Dr. Wm. Anthony Connolly

This incredible memoir, No Time

to Say Goodbye, tells of entertaining angels, dancing with devils, and of the

abandoned children many viewed simply as raining manna from some lesser god.

The young and unfortunate lives

of the Tuohy bruins—sometimes Irish, sometimes Jewish, often Catholic,

rambunctious, but all imbued with Lion’s hearts—told here with brutal honesty

leavened with humor and laudable introspective forgiveness. The memoir will

have you falling to your knees thanking that benevolent Irish cop in the sky, your

lucky stars, or hugging the oxygen out of your own kids the fate foisted upon

Johnny and his siblings does not and did not befall your own brood. John

William Tuohy, a nationally-recognized authority on organized crime and Irish

levity, is your trusted guide through the weeds the decades of neglect ensnared

he and his brothers and sisters, all suffering for the impersonal and often

mercenary taint of the foster care system. Theirs, and Tuohy’s, story is not at

all figures of speech as this review might suggest, but all too real and all

too sad, and maddening. I wanted to scream. I wanted to get into a time

machine, go back and adopt every last one of them. I was angry. I was

captivated. The requisite damning verities of foster care are all here, regretfully,

but what sets this story above others is its beating heart, even a bruised and

broken one, still willing to forgive and understand, and continue to aid its

walking wounded. I cannot recommend this book enough.

By Paul Dayon June 15, 2015

Great reading. Life in foster

care told from a very rare point of view.

By Jackie Malkeson June 5, 2015

This book is definitely a must

for social workers working with children specifically. This is an excellent

memoir which identifies the trails of foster children in the 1960s in the

United States. The memoir captures stories of joy as well as nail biting

terror, as the family is at times torn apart but finds each other later and

finds solace in the experiences of one another. The stories capture the love

siblings have for one another as well as the protection they have for one

another in even the worst of circumstances. On the flip side, one of the most

touching stories to me was when a Nun at the school helped him to read-- truly

an example of how a positive person really helped to shape the author in times

when circumstances at home were challenging and treacherous. I found the book

to be a page turner and at times show how even in the hardest of circumstances

there was a need to live and survive and make the best of any moment. The

memoir is eye-opening and helped to shed light and make me feel proud of the

volunteer work I take part in with disadvantaged children. Riveting....Must

read....memory lane on steroids....Catholic school banter, blue color

towns...Lawrence Welk on Sundays night's.

By eileenon June 4, 2015

From ' No time to say Goodbye

'and authors John W. Touhys Gangster novels, his style never waivers...humorous

to sadness to candidly realistic situations all his writings leaves the reader

in awe......longing for more.

By karen pojakeneon June 1, 2015

This book is a must-read for

anyone who administers to the foster care program in any state. This is not a

"fell through the cracks" life story, but rather a memoir of a life

guided by strength and faith and a hard determination to survive. it is

heartening to know that the "sewer" that life can become to steal our

personal peace can be fought and our peace can be restored, scarred, but

restored.

By Michelle Blackon

A captivating, shocking, and

deeply moving memoir, No Time to Say Goodbye is a true page turner. John shares

the story of his childhood, from the struggles of living in poverty to being in

the foster care system and simply trying to survive. You will be cheering for

him all the way, as he never loses his will to thrive even in the darkest and

bleakest of circumstances. This memoir is a very truthful and unapologetic

glimpse into the way in which some of our most vulnerable citizens have been

treated in the past and are still being treated today. It is truly eye-opening,

and hopefully will inspire many people to take action in protection of

vulnerable children.

By Kimberlyon May 24, 2015

I found myself in tears while

reading this book. John William Tuohy writes quite movingly about the world he

grew up in; a world in which I had hoped did not exist within the foster care

system. This book is at times funny, raw, compelling, heartbreaking and

disturbing. I found myself rooting for John as he tries to escape from an

incredibly difficult life. You will too!

By Geoffrey A. Childson May 20, 2015

I found this book to be a

compelling story of life in the Ct foster care system. at times disturbing and

at others inspirational ,The author goes into great detail in this gritty

memoir of His early life being abandoned into the states system and his

subsequent escape from it. Every once in a while a book or even an article in a

newspaper comes along that bears witness to an injustice or even something

that's just plain wrong. This chronicle of the foster care system is such a

book and should be required reading for any aspiring social workers.

John William Tuohy is a writer who lives in Washington DC. He holds an MFA in writing from Lindenwood University.

He is the author of No Time to Say Goodbye: Memoirs of a Life in Foster Care and Short Stories from a Small Town. He is also the author of numerous non-fiction on the history of organized crime including the ground break biography of bootlegger Roger Tuohy "When Capone's Mob Murdered Touhy" and "Guns and Glamour: A History of Organized Crime in Chicago."

His non-fiction crime short stories have appeared in The New Criminologist, American Mafia and other publications. John won the City of Chicago's Celtic Playfest for his work The Hannigan's of Beverly, and his short story fiction work, Karma Finds Franny Glass, appeared in AdmitTwo Magazine in October of 2008.

His play, Cyberdate.Com, was chosen for a public performance at the Actors Chapel in Manhattan in February of 2007 as part of the groups Reading Series for New York project. In June of 2008, the play won the Virginia Theater of The First Amendment Award for best new play.

Contact John:

MYWRITERSSITE.BLOGSPOT.COM

JWTUOHY95@GMAIL.COM

Editorial

Reviews

From

Publishers Weekly

JFK's

pardons and the mob; Prohibition, Chicago's crime cadres and the staged

kidnapping of "`Jake the Barber'" Factor, "the black sheep brother

of the cosmetics king, Max Factor"; lifetime sentences, attempted jail

busts and the perseverance of "a rumpled private detective and an

eccentric lawyer" John W. Tuohy showcases all these and more sensational

and shady happenings in When Capone's Mob Murdered Roger Touhy: The Strange

Case of Touhy, Jake the Barber and the Kidnapping that Never Happened. The

author started investigating Touhy's 1959 murder by Capone's gang in 1975 for

an undergrad assignment. He traces the frame-job whereby Touhy was accused of

the kidnapping, his decades in jail, his memoirs, his retrial and release and,

finally, his murder, 28 days after regaining his freedom. Sixteen pages of

photos.

From

Library Journal

Roger

Touhy, one of the "terrible Touhys" and leader of a bootlegging

racket that challenged Capone's mob in Prohibition Chicago, had a lot to answer

for, but the crime that put him behind bars was, ironically, one he didn't

commit: the alleged kidnapping of Jake Factor, half-brother of Max Factor and

international swindler. Author Tuohy (apparently no relation), a former staff

investigator for the National Center for the Study of Organized Crime, briefly

traces the history of the Touhys and the Capone mob, then describes Factor's

plan to have himself kidnapped, putting Touhy behind bars and keeping himself

from being deported. This miscarriage of justice lasted 17 years and ended in

Touhy's parole and murder by the Capone mob 28 days later. Factor was never

deported. The author spent 26 years researching this story, and he can't bear

to waste a word of it. Though slim, the book still seems padded, with

irrelevant detail muddying the main story. Touhy is a hard man to feel sorry

for, but the author does his best. Sure to be popular in the Chicago area and

with the many fans of mob history, this is suitable for larger public libraries

and regional collections. Deirdre Bray Root, Middletown P.L., OH

BOOK

REVIEW

John

William Tuohy, one of the most prolific crime writers in America, has penned a

tragic, but fascinating story of Roger Touhy and John Factor. It's a tale born

out of poverty and violence, a story of ambition gone wrong and deception on an

enormous, almost unfathomable, scale. However, this is also a story of triumph

of determination to survive, of a lifelong struggle for dignity and redemption

of the spirit.

The

story starts with John "Jake the Barber" Factor. The product of the

turn of the century European ethnic slums of Chicago's west side, Jake's

brother, Max Factor, would go on to create an international cosmetic empire.

In

1926, Factor, grubstaked in a partnership with the great New York criminal

genius, Arnold Rothstien, and Chicago's Al Capone, John Factor set up a stock

scam in England that fleeced thousands of investors, including members of the

royal family, out of $8 million dollars, an incredible sum of money in 1926.

After

the scam fell apart, Factor fled to France, where he formed another syndicate

of con artists, who broke the bank at Monte Carlo by rigging the tables.

Eventually,

Factor fled to the safety of Capone's Chicago but the highest powers in the

Empire demanded his arrest. However, Factor fought extradition all the way to

the United States Supreme Court, but he had a weak case and deportation was

inevitable. Just 24 hours before the court was to decide his fate, Factor paid

to have himself kidnapped and his case was postponed. He reappeared in Chicago

several days later, and, at the syndicates' urging, accused gangster Roger

Touhy of the kidnapping.

Roger

"The Terrible" Touhy was the youngest son of an honest Chicago cop.

Although born in the Valley, a teeming Irish slum, the family moved to rural

Des Plains, Illinois while Roger was still a boy. Touhy's five older brothers

stayed behind in the valley and soon flew under the leadership of

"Terrible Tommy" O'Connor. By 1933, three of them would be shot dead

in various disputes with the mob and one, Tommy, would lose the use of his legs

by syndicate machine guns. Secure in the still rural suburbs of Cook County,

Roger Touhy graduated as class valedictorian of his Catholic school.

Afterwards, he briefly worked as an organizer for the Telegraph and

Telecommunications Workers Union after being blacklisted by Western Union for

his minor pro-labor activities.

Touhy

entered the Navy in the first world war and served two years, teaching Morse

code to Officers at Harvard University.

After

the war, he rode the rails out west where he earned a living as a railroad

telegraph operator and eventually made a small but respectable fortune as an

oil well speculator.

Returning

to Chicago in 1924, Touhy married his childhood sweetheart, regrouped with his

brothers and formed a partnership with a corrupt ward heeler named Matt Kolb,

and, in 1925, he started a suburban bootlegging and slot machine operation in

northwestern Cook County. Left out of the endless beer wars that plagued the

gangs inside Chicago, Touhy's operation flourished. By 1926, his slot machine

operations alone grossed over $1,000,000.00 a year, at a time when a gallon of

gas cost eight cents.

They

were unusual gangsters. When the Klu Klux Klan, then at the height of its

power, threatened the life of a priest who had befriended the gang, Tommy

Touhy, Roger's older brother, the real "Terrible Touhy," broke into

the Klan's national headquarters, stole its membership roles, and, despite an

offer of $25,000 to return them, delivered the list to the priest who published

the names in several Catholic newspapers the following day.

Once,

Touhy unthinkingly released several thousand gallons of putrid sour mash in to

the Des Plains River one day before the city was to reenact its discovery by

canoe-riding Jesuits a hundred years before. After a dressing down by the towns

people Touhy spent $10,000.00 on perfume and doused the river with it, saving

the day.

They

were inventive too. When the Chicago police levied a 50% protection tax on

Touhy's beer, Touhy bought a fleet of Esso gasoline delivery trucks, kept the

Esso logo on the vehicles, and delivered his booze to his speakeasies that way.

In

1930, when Capone invaded the labor rackets, the union bosses, mostly Irish and

completely corrupt, turned to the Touhy organization for protection. The

intermittent gun battles between the Touhys and the Capone mob over control of

beer routes which had been fought on the empty, back roads of rural Cook

County, was now brought into the city where street battles extracted an awesome

toll on both sides. The Chicago Tribune estimated the casualties to be one hundred

dead in less then 12 months.

By

the winter of 1933, remarkably, Touhy was winning the war in large part because

joining him in the struggle against the mob was Chicago's very corrupt, newly

elected mayor Anthony "Ten percent Tony" Cermak, who was as much a

gangster as he was an elected official.

Cermak

threw the entire weight of his office and the whole Chicago police force behind

Touhy's forces. Eventually, two of Cermak's police bodyguards arrested Frank

Nitti, the syndicate's boss, and, for a price, shot him six times. Nitti lived.

As a result, two months later Nitti's gunmen caught up with Cermak at a

political rally in Florida.

Using

previously overlooked Secret Service reports, this book proves, for the first

time, that the mob stalked Cermak and used a hardened felon to kill him. The

true story behind the mob's 1933 murder of Anton Cermak, will changes histories

understanding of organized crimes forever. The fascinating thing about this

killing is its eerie similarity to the Kennedy assassination in Dallas thirty

years later, made even more macabre by the fact that several of the names

associated with the Cermak killing were later aligned with the Kennedy killing.

For

many decades, it was whispered that the mob had executed Cermak for his role in

the Touhy-syndicate war of 1931-33, but there was never proof. The official

story is that a loner named Giuseppe Zangara, an out-of-work, Sicilian born

drifter with communist leanings, traveled to Florida in the winter of 1933 and

fired several shots at President Franklin Roosevelt. He missed the President,

but killed Chicago's Mayor Anton Cermak instead. However, using long lost

documents, Tuohy is able to prove that Zangara was a convicted felon with long

ties to mob Mafia and that he very much intended to murder Anton Cermak.

With

Cermak dead, Touhy was on his own against the mob. At the same time, the United

States Postal Service was closing in on his gang for pulling off the largest

mail heists in US history at that time. The cash was used to fund Touhy's war

with the Capones.Then in June of 1933, John Factor en he reappeared, Factor

accused Roger Touhy of kidnapping him. After two sensational trials, Touhy was

convicted of kidnapping John Factor and sentenced to 99 years in prison and

Factor, after a series of complicated legal maneuvers, and using the mob's

influence, was allowed to remain in the United States as a witness for the

prosecution, however, he was still a wanted felon in England.

By

1942 Roger Touhy had been in prison for nine years, his once vast fortune was

gone. Roger's family was gone as well. At his request, his wife Clara had moved

to Florida with their two sons in 1934. However, with the help of Touhy's

remaining sister, the family retained a rumpled private detective, actually a

down-and-out, a very shady and disbarred mob lawyer named Morrie Green.

Disheveled

of not, Green was a highly competent investigator and was able to piece

together and prove the conspiracy that landed Touhy in jail. However, no court

would hear the case, and by the fall of 1942, Touhy had exhausted every legal

avenue open to him.Desperate, Touhy hatched a daring daylight breakout over the

thirty foot walls of Stateville prison.The sensational escape ended three

months later in a dramatic and bloody shootout between the convicts and the

FBI, led by J. Edgar Hoover.

Less

then three months after Touhy was captured, Fox Studios hired producer Brian

Foy to churn out a mob financed docudrama film on the escape entitled,

"Roger Touhy, The Last Gangster." The executive producer on the film

was Johnny Roselli, the hood who later introduced Judy Campbell to Frank

Sinatra. Touhy sued Fox and eventually won his case and the film was withdrawn

from circulation. In 1962, Columbia pictures and John Houston tried to produce

a remake of the film, but were scared off the project.

While

Touhy was on the run from prison, John Factor was convicted for m ail fraud and

was sentenced and served ten years at hard labor. Factor's take from the scam

was $10,000,000.00 in cash.

Released

in 1949, Factor took control of the Stardust Hotel Casino in 1955, then the

largest operation on the Vegas strip. The casino's true owners, of course, were

Chicago mob bosses Paul Ricca, Tony Accardo, Murray Humpreys and Sam Giancana.

From 1955 to 1963, the length of Factor's tenure at the casino, the US Justice

Department estimated that the Chicago outfit skimmed between forty-eight to 200

million dollars from the Stardust alone.

In

1956, while Factor and the outfit were growing rich off the Stardust, Roger

Touhy hired a quirky, high strung, but highly effective lawyer named Robert B.

Johnstone to take his case. A brilliant legal tactician, who worked incessantly

on Touhy's freedom, Robert Johnstone managed to get Touhy's case heard before

federal judge John P. Barnes, a refined magistrate filled with his own

eccentricities. After two years of hearings, Barnes released a 1,500-page

decision on Touhy's case, finding that Touhy was railroaded to prison in a conspiracy

between the mob and the state attorney's office and that John Factor had

kidnapped himself as a means to avoid extradition to England.

Released

from prison in 1959, Touhy wrote his life story "The Stolen Years"

with legendary Chicago crime reporter, Ray Brennan. It was Brennan, as a young

cub reporter, who broke the story of John Dillenger's sensational escape from

Crown Point prison, supposedly with a bar of soap whittled to look like a

pistol. It was also Brennan who brought about the end of Roger Touhy's mortal

enemy, "Tubbo" Gilbert, the mob owned chief investigator for the Cook

County state attorney's office, and who designed the frame-up that placed Touhy

behind bars.

Factor

entered a suit against Roger Touhy, his book publishers and Ray Brennan,

claiming it damaged his reputation as a "leading citizen of Nevada and a

philanthropist."

The

teamsters, Factor's partners in the Stardust Casino, refused to ship the book

and Chicago's bookstore owners were warned by Tony Accardo, in person, not to

carry the book.

Touhy

and Johnstone fought back by drawing up the papers to enter a $300,000,000

lawsuit against John Factor, mob leaders Paul Ricca, Tony Accardo and Murray

Humpreys as well as former Cook County state attorney Thomas Courtney and Tubbo

Gilbert, his chief investigator, for wrongful imprisonment.

The

mob couldn't allow the suit to reach court, and considering Touhy's

determination, Ray Brennan's nose for a good story and Bob Johnstone's legal

talents, there was no doubt the case would make it to court. If the case went

to court, John Factor, the outfit's figurehead at the lucrative Stardust

Casino, could easily be tied in to illegal teamster loans. At the same time,

the McClellan committee was looking into the ties between the teamsters, Las

Vegas and organized crime and the raid at the mob conclave in New York state

had awakened the FBI and brought them into the fight. So, Touhy's lawsuit was,

in effect, his death sentence.

Twenty-five

days after his release from twenty-five years in prison, Roger Touhy was gunned

down on a frigid December night on his sister's front door.

Two

years after Touhy's murder, in 1962, Attorney General Robert Kennedy ordered

his Justice Department to look into the highly suspect dealings of the Stardust

Casino. Factor was still the owner on record, but had sold his interest in the

casino portion of the hotel for a mere 7 million dollars. Then, in December of

that year, the INS, working with the FBI on Bobby Kennedy's orders, informed Jake

Factor that he was to be deported from the United States before the end of the

month. Factor would be returned to England where he was still a wanted felon as

a result of his 1928 stock scam. Just 48 hours before the deportation, Factor,

John Kennedy's largest single personal political contributor, was granted a

full and complete Presidential pardon which allowed him to stay in the United

States.

The

story hints that Factor was more then probably an informant for the Internal

Revenue Service, it also investigates the murky world of Presidential pardons,

the last imperial power of the Executive branch. It's a sordid tale of abuse of

privilege, the mob's best friend and perhaps it is time the American people

reconsider the entire notion.

The

mob wasn't finished with Factor. Right after his pardon, Factor was involved in

a vague, questionable financial plot to try and bail teamster boss Jimmy Hoffa

out of his seemingly endless financial problems in Florida real estate. He was

also involved with a questionable stock transaction with mobster Murray

Humpreys. Factor spent the remaining twenty years of his life as a benefactor

to California's Black ghettos. He tried, truly, to make amends for all of the

suffering he had caused in his life. He spent millions of dollars building

churches, gyms, parks and low cost housing in the poverty stricken ghettos.

When he died, three United States Senators, the Mayor of Los Angles and several

hundred poor Black waited in the rain to pay their last respects at Jake the Barber's

funeral.

Crime

don't pay, kids

Very good organized crime book. A

rather obscure gangster story which makes it fresh to read. I do not like these

minimum word requirements for a review. (There, I have met my minimum)

Chicago

Gangster History At It's Best

ByJ. CROSBYon

As a 4th generation Chicagoan, I just

loved this book. Growing up in the 1950's and 60's I heard the name

"Terrible Touhy's" mentioned many times. Roger was thought of as a

great man, and seems to have been held in high esteem among the old timer

Chicagoans.

That said, I thought this book to

be nothing but interesting and well written. (It inspired me to find a copy of

Roger's "Stolen Years" bio.) I do recommend this book to other folks

interested in prohibition/depression era Chicago crime research. It is a must

have for your library of Gangsters literature from that era. Chock full of

information and the reader is transported back in time.

I'd like to know just what is

"The Valley" area today in Chicago. I still live in the Windy City

and would like to see if anything remains from the early days of the 20th

century.

A good writer and a good book! I

will buy some more of Mr. Tuohy's work.

Great

story, great read

ByBookreaderon

A complex tale of gangsters,

political kickback, mob wars and corrupt politicians told with wit and humor at

a good pace. Highly recommend this book.

One

of the best books I've read in a long time....

If you're into mafioso, read

this! I loved it. Bought a copy for my brother to read for his

birthday--good stuff.

AND HERE'S SOME ANIMALS FOR YOU...................

Plaster cast of guard dog left chained to a post to guard the House of Orpheus in Pompeii. Remains of the bronze collar are still visible. 79 AD