I think that if God forgives us

we must forgive ourselves. Otherwise, it is almost like setting up ourselves as

a higher tribunal than Him. C.S. Lewis

Passing thoughts........................

In regard to the merciless murders

in California this week, don’t hate, but do recall the words of Isaac Asimov “Violence

is the last refuge of the incompetent”. Yet I could not understand the mindlessness of the act and then I understood that while I was trying to

clear my head and what I really should have doing was clearing my heart because

I know that within my heart truth is found and the truth is that within every

awful, painful and unacceptable moment we must live through, the heart knows

what the heart doesn’t; that goodness is concealed in that pain and beneath that

goodness there is a seed of grace.

MUSIC FOR THE SOUL

One cannot better examine the depth of a man’s

musical knowledge than by attempting to learn how far he has come in his

admiration for the works of Bach Thomas

Mann, Doctor Faustus

Woodward/Newman Drama Award 2016

NOTE: The fee will be waived for

Dramatist Guild members with an enclosed photocopy of a membership card.

The BPP is accepting submissions

for the 2015-16 Woodward/Newman Drama Award. Submissions are due by March 1,

2016. The top 10 finalists will be announced at the end of May with the winner

announced in June 2016.

"Full-length" plays

will have a complete running time of between 1 hour 15 minutes (75 minutes) to

2 hours 15 minutes (135 minutes).

Plays submitted must be

unpublished at the time of submission. Plays that have received developmental

readings, workshop productions, or productions at small theatre companies are

acceptable. No scripts with previous productions at major regional theaters

will be accepted. Once entered, subsequent activity does not change the

acceptability of the script.

Each submission must include a

synopsis (1 page or less) including the cast size. A separate page should

include a brief bio of the playwright, and production/development history if

applicable.

***

Taboo is looking for submissions

again! We have wanted to do this for a while and we are very excited that now

is the time. This year, instead of Grand Guignol plays, we are looking for

original adult fairy tales, exploring diverse taboos. Our showcase will have

the theme “The Uncanny: When the Fantasy is Too Real.”

Here are the requirements:

–Submissions must be accompanied

by a 150-250 word description of which taboo your work is exploring and how.

–The plays can be either

completely original, adaptations of classical works or other material that fits

the requirements of this genre.

–The plays must be 10-25 minutes

long.

–The plays should not require

elaborate sets, pro

***

The Simons Center for Geometry

and Physics, in its ongoing mission to explore the intersection science and

art, announces a CALL FOR PLAYS for the 2015-16 SBU Science Playwriting

Competition. The event is made possible by the generous support of the Simons

Center, the C. N. Yang Institute for Theoretical Physics, and the SBU

Department of Theatre Arts.

Calling all talented playwrights

with an interest in the sciences, and talented scientists with an interest in

the theatre to compose a ten-minute play with a substantial science component.

This contest is open to the general public:

First Prize Winner: $500

Second Prize Winner: $200

3rd Prize Winner: $100

Bringing science and theatre

together can provide the inspiration for a play of exceptional artistic merit

and lead to exciting new ways of learning about science. Indeed, we believe the

best science plays can be great works of art because of the science they

contain and great educational tools because of their artistic value. We are

recruiting Stony Brook University’™s brightest minds to write great plays that

make science accessible to a wide audience.

*** FOR MORE INFORMATION on these

and other opportunities see the web site athttp://www.nycplaywrights.org ***

--

You received this message because

you are subscribed to the Google Groups "NYCPlaywrights" group.

To post to this group, send email

to nycplaywrights_group@googlegroups.com.

Visit this group at

http://groups.google.com/group/nycplaywrights_group.

WHERE THE ART DOLLARS GO.......................

HERE'S SOME NICE ART FOR YOU TO LOOK AT....ENJOY!

Edouard Manet

Edouard Manet (1832-1883) was a study in contradictions. A Parisian bourgeois flaneur, he became associated with the avant-garde painters known now as the impressionists. He had a traditional art education and admired the old masters, but he developed a loose, painterly technique and preferred to paint scenes of everyday urban life.

Viewed as a trailblazer of the

impressionist movement, he was influenced by fellow artists Monet, Renoir,

Degas, and supported by art critics like Emile Zola. But he turned down

invitations to exhibit at the impressionists’ group shows, and pursued success

through the more traditional Paris Salon. It was a frustrating choice, as there

seemed to be no way to predict the Salon jury reaction’s to his submissions.

Manet’s final work, A Bar at the

Folies Bergere, was shown at the Salon of 1882; he died the next year. It was a

masterpiece that clearly trumpeted Manet as a premier painter of modern life

who chose to follow his own vision to the end.

Black and White Photo from Warhols Factory in New York

HERE'S PLEASANT POEM FOR YOU TO ENJOY................

Winter

Winds, Cold and Bleak

by

John Clare

Winter winds cold and blea

Chilly blows o'er the lea:

Wander not out to me,

Jenny so fair,

Wait in thy cottage free.

I will be there.

Wait in thy cushioned chair

Wi' thy white bosom bare.

Kisses are sweetest there:

Leave it for me.

Free from the chilly air

I will meet thee.

How sweet can courting prove,

How can I kiss my love

Muffled in hat and glove

From the chill air?

Quaking beneath the grove,

What love is there!

Lay by thy woollen vest,

Drape no cloak o'er thy breast:

Where my hand oft hath pressed,

Pin nothing there:

Where my head droops to rest,

Leave its bed bare.

John Clare (13 July 1793 – 20 May

1864) was an English poet, the son of a farm laborer, who came to be known for

his celebratory representations of the English countryside and his lamentation

of its disruption. His poetry underwent a major re-evaluation in the late 20th

century, and he is now often considered to be among the most important

19th-century poets.

His biographer Jonathan Bate

states that Clare was "the greatest laboring-class poet that England has

ever produced. No one has ever written more powerfully of nature, of a rural

childhood, and of the alienated and unstable self".

In his time, Clare was commonly

known as "the Northamptonshire Peasant Poet". His formal education

was brief, his other employment and class-origins were lowly. Clare resisted

the use of the increasingly standardized English grammar and orthography in his

poetry and prose, alluding to political reasoning in comparing

"grammar" (in a wider sense of orthography) to tyrannical government

and slavery, personifying it in jocular fashion as a "bitch".

He wrote in his Northamptonshire

dialect, introducing local words to the literary canon such as

"pooty" (snail), "lady-cow" (ladybird), "crizzle"

(to crisp) and "throstle" (song thrush).

In his early life he struggled to

find a place for his poetry in the changing literary fashions of the day. He

also felt that he did not belong with other peasants.

Clare once wrote: "I live here among the

ignorant like a lost man in fact like one whom the rest seems careless of

having anything to do with—they hardly dare talk in my company for fear I

should mention them in my writings and I find more pleasure in wandering the

fields than in musing among my silent neighbors who are insensible to

everything but toiling and talking of it and that to no purpose."

It is common to see an absence of

punctuation in many of Clare's original writings, although many publishers felt

the need to remedy this practice in the majority of his work. Clare argued with

his editors about how it should be presented to the public.

Clare grew up during a period of

massive changes in both town and countryside as the Industrial Revolution swept

Europe. Many former agricultural workers, including children, moved away from

the countryside to over-crowded cities, following factory work. The

Agricultural Revolution saw pastures ploughed up, trees and hedges uprooted,

the fens drained and the common land enclosed. This destruction of a

centuries-old way of life distressed Clare deeply. His political and social

views were predominantly conservative ("I am as far as my politics reaches

'King and Country'—no Innovations in Religion and Government say I."). He

refused even to complain about the subordinate position to which English

society relegated him, swearing that "with the old dish that was served to

my forefathers I am content.”

His early work delights both in

nature and the cycle of the rural year. Poems such as "Winter

Evening", "Haymaking" and "Wood Pictures in summer"

celebrate the beauty of the world and the certainties of rural life, where

animals must be fed and crops harvested. Poems such as "Little Trotty

Wagtail" show his sharp observation of wildlife, though The Badgershows

his lack of sentiment about the place of animals in the countryside. At this

time, he often used poetic forms such as the sonnet and the rhyming couplet.

His later poetry tends to be more meditative and uses forms similar to the folk

songs and ballads of his youth. An example of this is Evening.

His knowledge of the natural

world went far beyond that of the major Romantic poets. However, poems such as

"I Am" show a metaphysical depth on a par with his contemporary poets

and many of his pre-asylum poems deal with intricate play on the nature of

linguistics. His "bird's nest poems", it can be argued, illustrate

the self-awareness, and obsession with the creative process that captivated the

romantics. Clare was the most influential poet, aside from Wordsworth, to

practice in an older style.

GOOD WORDS

TO HAVE…………

Gramarye: (GRAM-uh-ree)

Occult learning; magic. From Old French gramaire (grammar, book of magic), from

Greek gramma (letter). Ultimately from the Indo-European root gerbh- (to

scratch), which also gave us crab, crayfish, carve, crawl, grammar, program, graphite,

glamor, anagram, paraph, andgraffiti.

Paragon \PAIR-uh-gahn\ A model of excellence or

perfection. Paragon derives from the Old Italian word paragone, which literally

means "touchstone." A touchstone is a black stone that was formerly

used to judge the purity of gold or silver. The metal was rubbed on the stone

and the color of the streak it left indicated its quality. In modern English,

both touchstone and paragon have come to signify a standard against which

something should be judged. Ultimately, paragon comes from the Greek parakonan,

meaning "to sharpen," from the prefixpara- ("alongside of")

and akonē, meaning "whetstone."

Emeritus \ih-MEH-ruh-tus\ 1: title corresponding to

that held last during active service 2 : retired from an office or position —

converted to emeriti after a pluralThe adjective emeritus is unusual in two

ways: it's frequently used postpositively (that is, after the noun it

modifies), and it has a plural form—emeriti—when it modifies a plural noun in

its second sense. If you've surmised from these qualities that the word is

Latin in origin, you are correct. Emeritus, which is the Latin past participle

of the verb emereri, meaning "to serve out one's term," was

originally used to describe soldiers who had completed their duty. (Emereri is

from the prefix e-, meaning "out," and merēre, meaning "to earn,

deserve, or serve"—also the source of our English word merit.) By the

beginning of the early 18th century, English speakers were using emeritus as an

adjective to refer to professors who had retired from office. The word

eventually became applied to other professions where a retired member may

continue to hold a title in an honorary capacity.

Colligate \KAH-luh-gayt\ 1 : to bind, unite, or group

together 2 :to subsume (isolated facts) under a general concept 3 : to be or become a member of a group

or unitColligate (not to be confused with collocate or collegiate) is a

technical term that descends from Latin colligare, itself fromcom-

("with") plus ligare ("to tie"). Ligature, ligament, lien,

rely, ally, oblige, furl, and league (in the sense of "an association of

persons, groups, or teams") can all be traced back along varying paths to

ligare. That leaves only collogue (meaning "to confer")—whose origin

is unknown. (Collocate and collegiate are also unrelated via ligare.)

Minatory

\MIN-uh-tor-ee\ having a menacing quality. Knowing that minatory means

"threatening," can you take a guess at a related word? If you're

familiar with mythology, perhaps you guessed Minotaur, the name of the

bull-headed, people-eating monster of Crete. Minotaur is a good guess, but as

terrifying as the monster sounds, its name isn't related to today's word. The

relative we're searching for is actuallymenace. Minatory and menace both come

from derivatives of the Latin verb minari, which means "to threaten."

Minatorywas borrowed directly from Late Latin minatorius. Menace came to

English via Anglo-French manace, menace, which came from Latin minac-, minax,

meaning "threatening."

Bibulous: (BIB-yuh-luhs1.

Excessively fond of drinking. 2. Highly absorbent. From Latin bibere (to

drink). Ultimately from the Indo-European root poi- (to drink), which also gave

us potion, poison, potable, beverage, and Sanskrit paatram (pot). Earliest

documented use: 1676.

I LOVE BLACK AND WHITE

PHOTOS FROM FILM

Gordon Parks photographs a Harlem family (1960s)

The Observation and Appreciation of Architecture

The Château de la

Mothe-Chandeniers is a castle at the town of Les Trois-Moutiers in the

Poitou-Charentes region of France. It was abandoned after a fire in 1932. It

has been abandoned ever since. Located in the midst of a large wood stands the

Château de la Motte-Chandeniers a former stronghold of the illustrious Bauçay

family, lords of Loudun. The stronghold dates to the thirteenth century and was

originally called Motte Bauçay (or Baussay).

The Motte Baussay was taken twice

by the English in the middle ages and devastated during the French Revolution.

It was bought in 1809 by François Hennecart, a wealthy business man who

undertook to restore its former glory. But it passed in 1857, to BaronLejeune

Edgar, Esquire of Napoleon III, son of the famous general and Amable Clary,

niece of the Queen of Sweden, Désirée Clary. A group of preservationists in

France are trying to save a 13th century castle that is slowly being reclaimed

by nature.

By Toni Aravadinos

Archaeologists believe

they may have discovered the lost city of Kane, the site of the epic sea battle

of Arginusae, which saw Athens crush Sparta in 406 BC. Archaeologists weren’t

exactly sure where this island was located, until now.

An international team of

archaeologists working with the German Archeological Institute think they may

have found Kane in the Aegean Sea, just off the coast of Turkey. The ancient

sea battle between the Athenians and Spartans is estimated to have happened

towards the end of the 27-year Peloponnesian War.

It was a bittersweet win for

the Athenians. Due to a storm the commanders abandoned thousands of their

shipwrecked men after the war, something that was considered very dishonorable

in the ancient times, as punishment six of them were executed and two were sent

into exile on their return to Athens.

The Battle of Arginusae got its

name due to its close proximity to the “Arginus” islands, which are now called

the Garip islands. Ancient texts always cited the Arginus islands as having

three land masses, though they are only two located where the Garip islands are

today. What happened to the third island has been a mystery.

Researchers wondered if a

nearby peninsula was perhaps the missing island, so they drilled into it and they

made an interesting discovery, they found evidence that what is now a peninsula

was once an island.

- See more at:

http://greece.greekreporter.com/2015/11/25/lost-ancient-greek-island-has-been-found/#sthash.ARN4s646.dpuf

(NOTE:) The naval Battle of Arginusae

took place in 406 BC during the Peloponnesian War near the city of Canae in the

Arginusae islands, east of the island of Lesbos. In the battle, an Athenian

fleet commanded by eight strategoi defeated a Spartan fleet under

Callicratidas. The battle was precipitated by a Spartan victory which led to

the Athenian fleet under Conon being blockaded at Mytilene; to relieve Conon,

the Athenians assembled a scratch force composed largely of newly constructed

ships manned by inexperienced crews. This inexperienced fleet was thus

tactically inferior to the Spartans, but its commanders were able to circumvent

this problem by employing new and unorthodox tactics, which allowed the

Athenians to secure a dramatic and unexpected victory.

The news of the victory itself

was met with jubilation at Athens, and the grateful Athenian public voted to

bestow citizenship on the slaves and metics who had fought in the battle. Their

joy was tempered, however, by the aftermath of the battle, in which a storm

prevented the ships assigned to rescue the survivors of the 25 disabled or

sunken Athenian triremes from performing their duties, and a great number of

sailors drowned. A fury erupted at Athens when the public learned of this, and

after a bitter struggle in the assembly six of the eight generals who had

commanded the fleet were tried as a group and executed.

At Sparta, meanwhile,

traditionalists who had supported Callicratidas pressed for peace with Athens,

knowing that a continuation of the war would lead to the re-ascendence of their

opponent Lysander. This party initially prevailed, and a delegation was

dispatched to Athens to make an offer of peace; the Athenians, however,

rejected this offer, and Lysander departed to the Aegean to take command of the

fleet for the remainder of the war, which would be decided less than a year

later by his total victory at Aegospotami.)

THE BEAT POETS

Beat

poetry evolved during the 1940s in both New York City and on the west coast,

although San Francisco became the heart of the movement in the early 1950s. The

end of World War II left poets like Allen Ginsberg, Gary Snyder, Lawrence

Ferlinghetti and Gregory Corso questioning mainstream politics and

culture. A Brief Guide to the Beat Poets | Academy of American Poets https://www.poets.org/poetsorg

On soft Spring nights I’ll stand in the yard under the stars - Something good will come out of all things yet - And it will be golden and eternal just like that - There’s no need to say another word. Jack Kerouac

“I’m an idealist

who has outgrown

my idealism

I have nothing to do

the rest of my life

and the rest of my life

to do it”

Jack Kerouac, Mexico City Blues

“‘We gotta go and never stop going 'till we get there.’ 'Where we going, man?’ 'I don’t know but we gotta go.’” Jack Kerouac, 'On the Road’

“I saw that my life was a vast glowing empty page and I could do anything I wanted.”Jack Kerouac, The Dharma Bums

“Dean’s California–wild, sweaty, important, the land of lonely and exiled and eccentric lovers come to forgather like birds, and the land where everybody somehow looked like broken-down, handsome, decadent movie actors.” Jack Kerouac, On the Road

“Great things are not accomplished by those who yield to trends, fads, or popular opinion.” Jack Keruoac

“There was nowhere to go but everywhere. So just keep on rolling under the stars.” Jack Kerouac, On the Road

“Love is only a recognition of our own guilt and imperfection, and a supplication for forgiveness to the perfect beloved. This is why we love those who are more beautiful than ourselves, why we fear them, and why we must be unhappy lovers. When we make ourselves high priests of art we deceive ourselves again, art is like a genie. It is more powerful than ourselves, but only by virtue of ourselves does it exist and create.” From a letter from Allen Ginsberg to Jack Kerouac, September, 1945

MISH MOSH..........................................

Mish Mash:

noun \ˈmish-ˌmash, -ˌmäsh\ A : hodgepodge, jumble

“The

painting was just a mishmash of colors and abstract shapes as far as we could

tell”. Origin Middle English & Yiddish; Middle English mysse

masche, perhaps reduplication of mash mash; Yiddish mish-mash, perhaps

reduplication of mishn to mix. First Known Use: 15th century

An 18 year old Mahatma Gandhi, 1887

GREAT WRITING

Then he starts hauling and mauling and talking to him in

Irish and the old towser growling, letting on to answer, like a duet in the

opera. Such growling you never heard as they let off between them. Someone that

has nothing better to do ought to write a letter _pro bono publico_ to the

papers about the muzzling order for a dog the like of that. Growling and

grousing and his eye all bloodshot from the drouth is in it and the hydrophobia

dropping out of his jaws. James Joyce, Ulysses

He smiled understandingly-much more than understandingly. It was one of those rare smiles with a quality of eternal reassurance in it that you may come across four or five times in life. It faced–or seemed to face–the whole eternal world for an instant, and then concentrated on you with an irresistible prejudice in your favor. It understood you just as far as you wanted to be understood, believed in you as you would like to believe in yourself, and assured you that it had precisely the impression of you that, at your best, you hoped to convey. F. Scott Fitzgerald, The Great Gatsby

HIS JOB By GRACE SARTWELL MASON

Against

an autumn sunset the steel skeleton of a twenty-story office

building

in process of construction stood out black and bizarre. It

flung up

its beams and girders like stern and yet airy music, orderly,

miraculously

strong, and delicately powerful. From the lower stories,

where

masons made their music of trowel and hammer, to the top, where

steam-riveters

rapped out their chorus like giant locusts in a summer

field,

the great building lived and breathed as if all those human

energies

that went to its making flowed warm through its steel veins.

In the

west window of a womans' club next door one of the members stood

looking

out at this building. Behind her at a tea-table three other

women sat

talking. For some moments their conversation had had a

plaintive

if not an actually rebellious tone. They were discussing the

relative

advantages of a man's work and a woman's, and they had arrived

at the

conclusion that a man has much the best of it when it comes to a

matter of

the day's work.

"Take

a man's work," said Mrs. Van Vechten, pouring herself a second cup

of tea.

"He chooses it; then he is allowed to go at it with absolute

freedom.

He isn't hampered by the dull, petty details of life that

hamper

us. He----"

"Details!

My dear, there you are right," broke in Mrs. Bullen. Two men,

first

Mrs. Bullen's father and then her husband, had seen to it that

neither

the biting wind of adversity nor the bracing air of experience

should

ever touch her. "Details! Sometimes I feel as if I were

smothered

by them. Servants, and the house, and now these relief

societies----"

She was

in her turn interrupted by Cornelia Blair. Cornelia was a

spinster

with more freedom than most human beings ever attain, her

father

having worked himself to death to leave her well provided for.

"The

whole fault is the social system," she declared. "Because of it men

have been

able to take the really interesting work of the world for

themselves.

They've pushed the dull jobs off onto us."

"You're

right, Cornelia," cried Mrs. Bullen. She really had nothing to

say, but

she hated not saying it. "I've always thought," she went on

pensively,

"that it would be so much easier just to go to an office in

the

morning and have nothing but business to think of. Don't you feel

that way

sometimes, Mrs. Trask?"

The woman

in the west window turned. There was a quizzical gleam in her

eyes as

she looked at the other three. "The trouble with us women is

we're

blind and deaf," she said slowly. "We talk a lot about men's work

and how

they have the best of things in power and freedom, but does it

occur to

one of us that a man _pays_ for power and freedom? Sometimes I

think

that not one of the women of our comfortable class would be

willing

to pay what our men pay for the power and freedom they get."

"What

do they pay?" asked Mrs. Van Vechten, her lip curling.

Mrs.

Trask turned back to the window. "There's something rather

wonderful

going on out here," she called. "I wish you'd all come and

look."

Just

outside the club window the steel-workers pursued their dangerous

task with

leisurely and indifferent competence, while over their head a

great

derrick served their needs with uncanny intelligence. It dropped

its chain

and picked a girder from the floor. As it rose into space two

figures

sprang astride either end of it. The long arm swung up and out;

the two

"bronco-busters of the sky" were black against the flame of the

sunset.

Some one shouted; the signalman pulled at his rope; the

derrick-arm

swung in a little with the girder teetering at the end of

the

chain. The most interesting moment of the steel-man's job had come,

when a

girder was to be jockeyed into place. The iron arm swung the

girder

above two upright columns, lowered it, and the girder began to

groove

into place. It wedged a little. One of the men inched along,

leaned

against space, and wielded his bar. The women stared, for the

moment

taken out of themselves. Then, as the girder settled into place

and the

two men slid down the column to the floor, the spectators turned

back to

their tea-table.

"Very

interesting," murmured Mrs. Van Vechten; "but I hardly see how it

concerns

us."

A flame

leaped in Mary Trask's face. "It's what we've just been talking

about,

one of men's jobs. I tell you, men are working miracles all the

time that

women never see. We envy them their power and freedom, but we

seldom

open our eyes to see what they pay for them. Look here, I'd like

to tell

you about an ordinary man and one of his jobs." She stopped and

looked

from Mrs. Bullen's perplexity to Cornelia Blair's superior smile,

and her

eyes came last to Sally Van Vechten's rebellious frown. "I'm

going to

bore you, maybe," she laughed grimly. "But it will do you good

to listen

once in a while to something _real_."

She sat

down and leaned her elbows on the table. "I said that he is an

ordinary

man," she began; "what I meant is that he started in like the

average,

without any great amount of special training, without money,

and

without pull of any kind. He had good health, good stock back of

him, an

attractive personality, and two years at a technical

school--those

were his total assets. He was twenty when he came to New

York to

make a place for himself, and he had already got himself engaged

to a girl

back home.

He had enough money to keep him for about three

weeks, if

he lived very economically. But that didn't prevent his

feeling a

heady exhilaration that day when he walked up Fifth Avenue for

the first

time and looked over his battle-field. He has told me often,

with a

chuckle at the audacity of it, how he picked out his employer.

All day

he walked about with his eyes open for contractors' signs.

Whenever

he came upon a building in the process of construction he

looked it

over critically, and if he liked the look of the job he made a

note of

the contractor's name and address in a little green book. For he

was to be

a builder--of big buildings, of course! And that night, when

he turned

out of the avenue to go to the cheap boarding-house where he

had sent

his trunk, he told himself that he'd give himself five years to

set up an

office of his own within a block of Fifth Avenue.

"Next

day he walked into the offices of Weil & Street--the first that

headed

the list in the little green book--asked to see Mr. Weil, and,

strangely

enough, got him, too. Even in those raw days Robert had a

cheerful

assurance tempered with rather a nice deference that often got

him what

he wanted from older men. When he left the offices of Weil &

Street he

had been given a job in the estimating-room, at a salary that

would

just keep him from starving.

He grew lean and lost his country color that winter, but he was learning,

learning

all the time, not only in the office of Weil & Street, but at

night school,

where he

studied architecture.

When he decided he had got all he could get out of the

estimating

and drawing rooms he asked to be transferred to one of the

jobs.

They gave him the position of timekeeper on one of the contracts,

at a

slight advance in salary.

"A

man can get as much or as little out of being timekeeper as he

chooses.

Robert got a lot out of it. He formulated that summer a working

theory of

the length of time it should take to finish every detail of a

building.

He talked with bricklayers, he timed them and watched them,

until he

knew how many bricks could be laid in an hour; and it was the

same way

with carpenters, fireproofers, painters, plasterers. He soaked

in a

thousand practical details of building: he picked out the best

workman

in each gang, watched him, talked with him, learned all he could

of that

man's particular trick; and it all went down in the little green

book.

For at the back of his head was always the thought of the time

when he

should use all this knowledge in his own business. Then one day

when he

had learned all he could learn from being timekeeper, he walked

into

Weil's office again and proposed that they make him one of the

firm's

superintendents of construction.

"Old

Weil fairly stuttered with the surprise of this audacious

proposition.

He demanded to know what qualifications the young man could

show for

so important a position, and Robert told him about the year he

had had

with the country builder and the three summer vacations with the

country

surveyor--which made no impression whatever on Mr. Weil until

Robert

produced the little green book. Mr. Weil glanced at some of the

figures

in the book, snorted, looked hard at his ambitious timekeeper,

who

looked back at him with his keen young eyes and waited. When he left

the

office he had been promised a tryout on a small job near the

offices,

where, as old Weil said, they could keep an eye on him. That

night he

wrote to the girl back home that she must get ready to marry

him at a

moment's notice."

Mrs.

Trask leaned back in her chair and smiled with a touch of sadness.

"The

wonder of youth! I can see him writing that letter, exuberant,

ambitious,

his brain full of dreams and plans--and a very inadequate

supper in

his stomach. The place where he lived--he pointed it out to me

once--was

awful. No girl of Rob's class--back home his folks were

'nice'--would

have stood that lodging-house for a night, would have

eaten the

food he did, or gone without the pleasures of life as he had

gone

without them for two years. But there, right at the beginning, is

the

difference between what a boy is willing to go through to get what

he wants

and what a girl would or could put up with. And along with a

better

position came a man's responsibility, which he shouldered alone.

"'I

was horribly afraid I'd fall down on the job,' he told me long

afterward.

'And there wasn't a living soul I could turn to for help. The

thing was

up to me alone!'"

Mrs.

Trask looked from Mrs. Bullen to Mrs. Van Vechten. "Mostly they

fight

alone," she said, as if she thought aloud. "That's one thing about

men we

don't always grasp--the business of existence is up to the

average

man alone. If he fails or gets into a tight place he has no one

to fall

back on, as a woman almost always has. Our men have a prejudice

against

taking their business difficulties home with them. I've a

suspicion

it's because we're so ignorant they'd have to do too much

explaining!

So in most cases they haven't even a sympathetic

understanding

to help them over the bad places. It was so with Robert

even

after he had married the girl back home and brought her to the

city.

His idea was to keep her from all worry and anxiety, and so, when

he came

home at night and she asked him if he had had a good day, or if

the work

had gone well, he always replied cheerfully that things had

gone

about the same as usual, even though the day had been a

particularly

bad one. This was only at first, however. The girl happened

to be the

kind that likes to know things. One night, when she wakened to

find him

staring sleepless at the ceiling, the thought struck her that,

after

all, she knew nothing of his particular problems, and if they were

partners

in the business of living why shouldn't she be an intelligent

member of

the firm, even if only a silent one?

"So

she began to read everything she could lay her hands on about the

business

of building construction, and very soon when she asked a

question

it was a fairly intelligent one, because it had some knowledge

back of

it. She didn't make the mistake of pestering him with questions

before

she had any groundwork of technical knowledge to build on, and

I'm not

sure that he ever guessed what she was up to, but I do know that

gradually,

as he found that he did not, for instance, have to draw a

diagram

and explain laboriously what a caisson was because she already

knew a

good deal about caissons, he fell into the habit of talking out

to her a

great many of the situations he would have to meet next day.

Not that

she offered her advice nor that he wanted it, but what helped

was the

fact of her sympathy--I should say her intelligent sympathy, for

that is

the only kind that can really help.

"So

when his big chance came along she was ready to meet it with him. If

he

succeeded she would be all the better able to appreciate his success;

and if he

failed she would never blame him from ignorance. You must

understand

that his advance was no meteoric thing. He somehow, by dint

of

sitting up nights poring over blueprints and text-books and by day

using his

wits and his eyes and his native shrewdness, managed to pull

off with

fair success his first job as superintendent; was given other

contracts

to oversee; and gradually, through three years of hard work,

learning,

learning all the time, worked up to superintending some of the

firm's

important jobs. Then he struck out for himself."

Mrs.

Trask turned to look out of the west window. "It sounds so easy,"

she

mused. "'Struck out for himself.' But I think only a man can quite

appreciate

how much courage that takes. Probably, if the girl had not

understood

where he was trying to get to, he would have hesitated longer

to give

up his good, safe salary; but they talked it over, she

understood

the hazards of the game, and she was willing to take a

chance.

They had saved a tiny capital, and only a little over five years

from the

day he had come to New York he opened an office within a block

of Fifth

Avenue.

"I won't

bore you with the details of the next two years, when he was

getting

together his organization, teaching himself the details of

office

work, stalking architects and owners for contracts. He acquired a

slight

stoop to his shoulders in those two years and there were days

when

there was nothing left of his boyishness but the inextinguishable

twinkle

in his hazel eyes. There were times when it seemed to him as if

he had

put to sea in a rowboat; as if he could never make port; but

after a

while small contracts began to come in, and then came along the

big

opportunity. Up in a New England city a large bank building was to

be built;

one of the directors was a friend of Rob's father, and Rob was

given a

chance to put in an estimate. It meant so much to him that he

would not

let himself count on getting the contract; he did not even

tell the

partner at home that he had been asked to put in an estimate

until one

day he came tearing in to tell her that he had been given the

job. It

seemed too wonderful to be true. The future looked so dazzling

that they

were almost afraid to contemplate it. Only something wildly

extravagant

would express their emotion, so they chartered a hansom cab

and went

gayly sailing up-town on the late afternoon tide of Fifth

Avenue;

and as they passed the building on which Robert had got his job

as

timekeeper he took off his hat to it, and she blew a kiss to it, and

a dreary

old clubman in a window next door brightened visibly!"

Mrs.

Trask turned her face toward the steel skeleton springing up across

the way

like the magic beanstalk in the fairy-tale. "The things men have

taught

themselves to do!" she cried. "The endurance and skill, the

inventiveness,

the precision of science, the daring of human wits, the

poetry

and fire that go into the making of great buildings! We women

walk in

and out of them day after day, blindly--and this indifference is

symbolical,

I think, of the way we walk in and out of our men's

lives....

I wish I could make you see that job of young Robert's so that

you would

feel in it what I do--the patience of men, the strain of the

responsibility

they carry night and day, the things life puts up to

them,

which they have to meet alone, the dogged endurance of them...."

Mrs.

Trask leaned forward and traced a complicated diagram on the

table-cloth

with the point of a fork. "It was his first big job, you

understand,

and he had got it in competition with several older

builders.

From the first they were all watching him, and he knew it,

which put

a fine edge to his determination to put the job through with

credit.

To be sure, he was handicapped by lack of capital, but his past

record

had established his credit, and when the foundation work was

begun it

was a very hopeful young man that watched the first shovelful

of earth

taken out.

But when they had gone down about twelve feet, with

a trench

for a retaining-wall, they discovered that the owners' boring

plan was

not a trustworthy representation of conditions; the job was

going to

be a soft-ground proposition. Where, according to the owners'

preliminary

borings, he should have found firm sand with a normal amount

of

moisture, Rob discovered sand that was like saturated oatmeal, and

beyond

that quicksand and water. Water! Why, it was like a subterranean

lake fed

by a young river! With the pulsometer pumps working night and

day they

couldn't keep the water out of the test pier he had sunk. It

bubbled

in as cheerfully as if it had eternal springs behind it, and

drove the

men out of the pier in spite of every effort. Rob knew then

what he

was up against. But he still hoped that he could sink the

foundations

without compressed air, which would be an immense expense he

had not

figured on in his estimate, of course.

So he devised a certain kind of concrete crib, the first one was driven--and when they got it

down

beneath quicksand and water about twenty-five feet, it hung up on a

boulder!

You see, below the stratum of sand like saturated oatmeal,

below the

water and quicksand, they had come upon something like a New

England

pasture, as thick with big boulders as a bun with currants! If

he had

spent weeks hunting for trouble he couldn't have found more than

was

offered him right there. It was at this point that he went out and

wired a

big New York engineer, who happened to be a friend of his, to

come up.

In a day or two the engineer arrived, took a look at the job,

and then

advised Rob to quit.

"'It's

a nasty job,' he told him. 'It will swallow every penny of your

profits

and probably set you back a few thousands. It's one of the worst

soft-ground

propositions I ever looked over.'

"Well

that night young Robert went home with a sleep-walking expression

in his

eyes. He and the partner at home had moved up to Rockford to be

near the

job while the foundation work was going on, so the girl saw

exactly

what he was up against and what he had to decide between.

"'I

could quit,' he said that night, after the engineer had taken his

train

back to New York, 'throw up the job, and the owners couldn't hold

me

because of their defective boring plans. But if I quit there'll be

twenty

competitors to say I've bit off more than I can chew. And if I

go on I

lose money; probably go into the hole so deep I'll be a long

time

getting out.'

"You

see, where his estimates had covered only the expense of normal

foundation

work he now found himself up against the most difficult

conditions

a builder can face. When the girl asked him if the owners

would not

make up the additional cost he grinned ruefully. The owners

were

going to hold him to his original estimate; they knew that with his

name to

make he would hate to give up; and they were inclined to be

almost as

nasty as the job.

"'Then

you'll have all this work and difficulty for nothing?' the girl

asked.

'You may actually lose money on the job?'

"'Looks

that way,' he admitted.

"'Then

why do you go on?' she cried.

"His

answer taught the girl a lot about the way a man looks at his job.

'If I

take up the cards I can't be a quitter,' he said. 'It would hurt

my

record. And my record is the equivalent of credit and capital. I

can't

afford to have any weak spots in it. I'll take the gaff rather

than have

it said about me that I've lain down on a job. I'm going on

with this

thing to the end.'"

Little

shrewd, reminiscent lines gathered about Mrs. Trask's eyes.

"There's

something exhilarating about a good fight. I've always thought

that if I

couldn't be a gunner I could get a lot of thrills out of just

handing

up the ammunition.... Well, Rob went on with the contract. With

the first

crib hung up on a boulder and the water coming in so fast they

couldn't

pump it out fast enough to dynamite, he was driven to use

compressed

air, and that meant the hiring of a compressor, locks,

shafting--a

terribly costly business--as well as bringing up to the job

a gang of

the high-priced labor that works under air. But this was done,

and the

first crib for the foundation piers went down slowly, with the

sand-hogs--men

that work in the caissons--drilling and blasting their

way week

after week through that underground New England pasture. Then,

below

this boulder-strewn stratum, instead of the ledge they expected

they

struck four feet of rotten rock, so porous that when air was put on

it to

force the water back great air bubbles blew up all through the

lot,

forcing the men out of the other caissons and trenches. But this

was a

mere dull detail, to be met by care and ingenuity like the others.

And at

last, forty feet below street level, they reached bed-rock.

Forty-six

piers had to be driven to this ledge.

"Rob

knew now exactly what kind of a job was cut out for him. He knew he

had not

only the natural difficulties to overcome, but he was going to

have to

fight the owners for additional compensation. So one day he went

into

Boston and interviewed a famous old lawyer.

"'Would

you object,' he asked the lawyer, 'to taking a case against

personal

friends of yours, the owners of the Rockford bank building?'

"'Not

at all--and if you're right, I'll lick 'em! What's your case?'

"Rob

told him the whole story. When he finished the famous man refused

to commit

himself one way or the other; but he said that he would be in

Rockford

in a few days, and perhaps he'd look at Robert's little job. So

one day,

unannounced, the lawyer appeared. The compressor plant was hard

at work

forcing the water back in the caissons, the pulsometer pumps

were

sucking up streams of water that flowed without ceasing into the

settling

tank and off into the city sewers, the men in the caissons were

sending

up buckets full of silt-like gruel. The lawyer watched

operations

for a few minutes, then he asked for the owners' boring plan.

When he

had examined this he grunted twice, twitched his lower lip

humorously,

and said: 'I'll put you out of this. If the owners wanted a

deep-water

lighthouse they should have specified one--not a bank

building.'

"So

the battle of legal wits began. Before the building was done Joshua

Kent had

succeeded in making the owners meet part of the additional cost

of the

foundation, and Robert had developed an acumen that stood by him

the rest

of his life. But there was something for him in this job bigger

than

financial gain or loss. Week after week, as he overcame one

difficulty

after another, he was learning, learning, just as he had done

at Weil

& Street's. His hazel eyes grew keener, his face thinner. For

the job

began to develop every freak and whimsy possible to a growing

building.

The owner of the department store next door refused to permit

access

through his basement, and that added many hundred dollars to the

cost of

building the party wall; the fire and telephone companies were

continually

fussing around and demanding indemnity because their poles

and

hydrants got knocked out of plumb; the thousands of gallons of dirty

water

pumped from the job into the city sewers clogged them up, and the

city sued

for several thousand dollars' damages; one day the car-tracks

in front

of the lot settled and valuable time was lost while the men

shored

them up; now and then the pulsometer engines broke down; the

sand-hogs

all got drunk and lost much time; an untimely frost spoiled a

thousand

dollars' worth of concrete one night. But the detail that

required

the most handling was the psychological effect on Rob's

subcontractors.

These men, observing the expensive preliminary

operations,

and knowing that Rob was losing money every day the

foundation

work lasted, began to ask one another if the young boss would

be able

to put the job through. If he failed, of course they who had

signed up

with him for various stages of the work would lose heavily.

Panic

began to spread among all the little army that goes to the making

of a big

building. The terra-cotta-floor men, the steel men,

electricians

and painters began to hang about the job with gloom in

their

eyes; they wore a path to the architect's door, and he, never

having

quite approved of so young a man being given the contract, did

little to

allay their apprehensions. Rob knew that if this kept up

they'd

hurt his credit, so he promptly served notice on the architect

that if

his credit was impaired by false rumors he'd hold him

responsible;

and he gave each subcontractor five minutes in which to

make up

his mind whether he wanted to quit or look cheerful. To a man

they

chose to stick by the job; so that detail was disposed of. In the

meantime

the sinking of piers for one of the retaining-walls was giving

trouble.

One morning at daylight Rob's superintendent telephoned him to

announce

that the street was caving in and the buildings across the way

were

cracking. When Rob got there he found the men standing about scared

and

helpless, while the plate-glass windows of the store opposite were

cracking

like pistols and the building settled. It appeared that when

the

trench for the south wall had gone down a certain distance water

began to

rush in under the sheeting as if from an underground river,

and, of

course, undermined the street and the store opposite. The pumps

were

started like mad, two gangs were put at work, with the

superintendent

swearing, threatening, and pleading to make them dig

faster,

and at last concrete was poured and the water stopped. That day

Rob and

his superintendent had neither breakfast nor lunch; but they had

scarcely

finished shoring up the threatened store when the owner of the

store

notified Rob that he would sue for damages, and the secretary of

the Y. W.

C. A. next door attempted to have the superintendent arrested

for

profanity. Rob said that when this happened he and his

superintendent

solemnly debated whether they should go and get drunk or

start a

fight with the sand-hogs; it did seem as if they were entitled

to some

emotional outlet, all the circumstances considered!

"So

after months of difficulties the foundation work was at last

finished.

I've forgotten to mention that there was some little

difficulty

with the eccentricities of the sub-basement floor. The wet

clay

ruined the first concrete poured, and little springs had a way of

gushing

up in the boiler-room. Also, one night a concrete shell for the

elevator

pit completely disappeared--sank out of sight in the soft

bottom.

But by digging the trench again and jacking down the bottom and

putting

hay under the concrete, the floor was finished; and that detail

was

settled.

"The

remainder of the job was by comparison uneventful. The things that

happened

were all more or less in the day's work, such as a carload of

stone for

the fourth story arriving when what the masons desperately

needed

was the carload for the second, and the carload for the third

getting

lost and being discovered after three days' search among the

cripples

in a Buffalo freight-yard. And there was a strike of

structural-steel

work workers which snarled up everything for a while;

and

always, of course, there were the small obstacles and differences

owners

and architects are in the habit of hatching up to keep a builder

from

getting indifferent. But these things were what every builder

encounters

and expects. What Rob's wife could not reconcile herself to

was the

fact that all those days of hard work, all those days and nights

of strain

and responsibility, were all for nothing. Profits had long

since

been drowned in the foundation work; Robert would actually have to

pay

several thousand dollars for the privilege of putting up that

building!

When the girl could not keep back one wail over this detail

her

husband looked at her in genuine surprise.

"'Why,

it's been worth the money to me, what I've learned,' he said.

'I've got

an education out of that old hoodoo that some men go through

Tech and

work twenty years without getting; I've learned a new wrinkle

in every

one of the building trades; I've learned men and I've learned

law, and

I've delivered the goods. It's been hell, but I wouldn't have

missed

it!'"

Mrs.

Trask looked eagerly and a little wistfully at the three faces in

front of

her. Her own face was alight. "Don't you see--that's the way a

real man

looks at his work; but that man's wife would never have

understood

it if she hadn't been interested enough to watch his job. She

saw him

grow older and harder under that job; she saw him often haggard

from the

strain and sleepless because of a dozen intricate problems; but

she never

heard him complain and she never saw him any way but

courageous

and often boyishly gay when he'd got the best of some

difficulty.

And furthermore, she knew that if she had been the kind of a

woman who

is not interested in her husband's work he would have kept it

to

himself, as most American husbands do. If he had, she would have

missed a

chance to learn a lot of things that winter, and she probably

wouldn't

have known anything about the final chapter in the history of

the job

that the two of them had fallen into the habit of referring to

as the

White Elephant. They had moved back to New York then, and the

Rockford

bank building was within two weeks of its completion, when at

seven

o'clock one morning their telephone rang. Rob answered it and his

wife

heard him say sharply: 'Well, what are you doing about it?' And

then:

'Keep it up. I'll catch the next train.'

"'What

is it?' she asked, as he turned away from the telephone and she

saw his

face.

"'The

department store next to the Elephant is burning,' he told her.

'Fireproof?

Well, I'm supposed to have built a fireproof building--but

you never

can tell.'

"His

wife's next thought was of insurance, for she knew that Robert had

to insure

the building himself up to the time he turned it over to the

owners.

'The insurance is all right?' she asked him.

"But

she knew by the way he turned away from her that the worst of all

their bad

luck with the Elephant had happened, and she made him tell

her. The

insurance had lapsed about a week before. Rob had not renewed

the

policy because its renewal would have meant adding several hundreds

to his

already serious deficit, and, as he put it, it seemed to him that

everything

that could happen to that job had already happened. But now

the last

stupendous, malicious catastrophe threatened him. Both of them

knew when

he said good-by that morning and hurried out to catch his

train

that he was facing ruin. His wife begged him to let her go with

him; at

least she would be some one to talk to on that interminable

journey;

but he said that was absurd; and, anyway, he had a lot of

thinking

to do. So he started off alone.

"At

the station before he left he tried to get the Rockford bank

building

on the telephone. He got Rockford and tried for five minutes to

make a

connection with his superintendent's telephone in the bank

building,

until the operator's voice came to him over the wire: 'I tell

you, you

can't get that building, mister. It's burning down!'

"'How

do you know?' he besought her.

"'I

just went past there and I seen it,' her voice came back at him.

"He

got on the train. At first he felt nothing but a queer dizzy vacuum

where his

brain should have been; the landscape outside the windows

jumbled

together like a nightmare landscape thrown up on a

moving-picture

screen. For fifty miles he merely sat rigidly still, but

in

reality he was plunging down like a drowning man to the very bottom

of

despair. And then, like the drowning man, he began to come up to the

surface

again.

The instinct for self-preservation stirred in him and

broke the

grip of that hypnotizing despair. At first slowly and

painfully,

but at last with quickening facility, he began to think, to

plan.

Stations went past; a man he knew spoke to him and then walked on,

staring;

but he was deaf and blind. He was planning for the future.

Already

he had plumbed, measured, and put behind him the fact of the

fire;

what he occupied himself with now was what he could save from the

ashes to

make a new start with. And he told me afterwards that actually,

at the

end of two hours of the liveliest thinking he had ever done in

his life,

he began to enjoy himself! His fighting blood began to tingle;

his head

steadied and grew cool; his mind reached out and examined every

aspect of

his stupendous failure, not to indulge himself in the weakness

of

regret, but to find out the surest and quickest way to get on his

feet

again. Figuring on the margins of timetables, going over the

contracts

he had in hand, weighing every asset he possessed in the

world, he

worked out in minute detail a plan to save his credit and his

future.

When he got off the train at Boston he was a man that had

already

begun life over again; he was a general that was about to make

the first

move in a long campaign, every move and counter-move of which

he

carried in his brain. Even as he crossed the station he was

rehearsing

the speech he was going to make at the meeting of his

creditors

he intended to hold that afternoon. Then, as he hastened

toward a

telephone-booth, he ran into a newsboy. A headline caught his

eye. He

snatched at the paper, read the headlines, standing there in the

middle of

the room. And then he suddenly sat down on the nearest bench,

weak and

shaking.

"On

the front page of the paper was a half-page picture of the Rockford

bank

building with the flames curling up against its west wall, and

underneath

it a caption that he read over and over before he could grasp

what it

meant to him. The White Elephant had not burned; in fact, at the

last it

had turned into a good elephant, for it had not only not burned

but it

had stopped the progress of what threatened to be a very

disastrous

conflagration, according to a jubilant despatch from

Rockford.

And Robert, reading these lines over and over, felt an amazing

sort of

indignant disappointment to think that now he would not have a

chance to

put to the test those plans he had so minutely worked out. He

was in

the position of a man that has gone through the painful process

of

readjusting his whole life; who has mentally met and conquered a

catastrophe

that fails to come off. He felt quite angry and cheated for

a few

minutes, until he regained his mental balance and saw how absurd

he was,

and then, feeling rather foolish and more than a little shaky,

he caught

a train and went up to Rockford.

"There

he found out that the report had been right; beyond a few cracked

wire-glass

windows--for which, as one last painful detail, he had to

pay--and

a blackened side wall, the Elephant was unharmed. The men

putting

the finishing touches to the inside had not lost an hour's work.

All that

dreadful journey up from New York had been merely one last turn

of the

screw.

"Two

weeks later he turned the Elephant over to the owners, finished, a

good,

workmanlike job from roof to foundation-piers. He had lost money

on it;

for months he had worked overtime his courage, his ingenuity, his

nerve,

and his strength. But that did not matter. He had delivered the

goods. I

believe he treated himself to an afternoon off and went to a

ball-game;

but that was all, for by this time other jobs were under way,

a whole

batch of new problems were waiting to be solved; in a week the

Elephant

was forgotten."

Mrs.

Trask pushed back her chair and walked to the west window. A

strange

quiet had fallen upon the sky-scraper now; the workmen had gone

down the

ladders, the steam-riveters had ceased their tapping. Mrs.

Trask

opened the window and leaned out a little.

Behind

her the three women at the tea-table gathered up their furs in

silence.

Cornelia Blair looked relieved and prepared to go on to dinner

at

another club, Mrs. Bullen avoided Mrs. Van Vechten's eye. In her rosy

face

faint lines had traced themselves, as if vaguely some new

perceptiveness

troubled her. She looked at her wristwatch and rose from

the table

hastily.

"I

must run along," she said. "I like to get home before John does. You

going my

way, Sally?"

Mrs. Van

Vechten shook her head absently. There was a frown between her

dark

brows; but as she stood fastening her furs her eyes went to the

west

window, with an expression in them that was almost wistful. For an

instant

she looked as if she were going over to the window beside Mary

Trask;

then she gathered up her gloves and muff and went out without a

word.

Mary

Trask was unaware of her going. She had forgotten the room behind

her and

her friends at the tea-table, as well as the other women

drifting

in from the adjoining room. She was contemplating, with her

little,

absent-minded smile, her husband's name on the builder's sign

halfway

up the unfinished sky-scraper opposite.

"Good

work, old Rob," she murmured. Then her hand went up in a quaint

gesture

that was like a salute. "To all good jobs and the men behind

them!"

she added.

Sculpture this and Sculpture

that

Antonio Canova (Italian pronunciation: November 1 1757

– October 13 1822) was an Italian neoclassical sculptor, famous for his marble

sculptures. Often regarded as the greatest of the neoclassical artists, his

artwork was inspired by the Baroque and the classical revival, but avoided the

melodramatics of the former, and the cold artificiality of the latter.

Cupid and Psyche (1808)

“Psyche Revived by Cupid’s Kiss“ - 1787

You have been told that, even like a chain, you are as weak

as your weakest link.

This is but half the truth.

You are also as strong as your strongest link.

To measure you by your smallest deed is to reckon the power

of the ocean

by the frailty of its foam.

To judge you by your failures is to cast blame upon the

seasons for their inconstancy.

Kahlil Gibran

THE ART OF PULP

THE ART OF WAR............

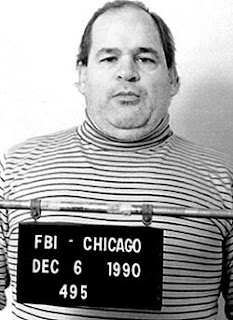

TODAY'S ALLEGED MOB GUY

Giorgio Basile AKA Angel Face is an alleged hit man for the 'Ndrangheta.

The New England Mafia.

Good

book about the New England mafia with some nice rare pictures

Coming

from RI - The book was great

This

held my interest, read it in two sittings, quite late at night. Most of the

main characters were familiar to me, being a born and bred New Englander, got a

kick out of some of the descriptions. A good easy read with lots of history and

Mafia insight.

READERS

REVIEWS FROM AMAZON BOOKS

A

detailed photographic account of the murders that shocked the underworld, the

St. Valentine's Day massacre. The author tells the story of what happened and

how it happened on that fateful day for the Northside gang and demonstrates

with photos. Good book.

Shooting

the Mob: Organized Crime in Photographs. Dutch Schultz. Paperback

READERS

REVIEWS FROM AMAZON BOOKS

Dutch

Schultz continues to capture and fascinate and his story, including his last

words, are detailed here with dozens of photographs from Schultz early days in

crime until the bitter end.

Dutch

Schultz (Arthur Flegenheimer) was the problem child of organized crime in New

York City in the 1920s and 1930s who made his fortune in bootlegging alcohol

and the numbers racket. The book gives a quick but accurate account of the

Dutchman's rise and his battle in two tax evasions trials led by prosecutor

Thomas Dewey. It covers his murder, probably on the orders of fellow mobster

Lucky Luciano. In an effort to avert his conviction, Schultz asked the

Commission for permission to kill Dewey, which they declined. After Schultz

disobeyed the Commission and attempted to carry out the hit, they ordered his

assassination in 1935. The book has a very fine series of photographs. Good

reading at a fair price.

Shooting

the mob. Organized crime in photos. Dead Mobsters, Gangsters and Hoods.

READERS

REVIEWS FROM AMAZON BOOKS

This

book covers the full gamut of gangsters with many excellent photos. The story

accompanying each slain hoodlum varies from a few pages to one or two lines.

The book suffers from atrocious editing of the text. Words are frequently

mispelled or missing, sentences often end half way through only to resume as a

new sentence and paragraphs sometimes end midsentence. There are also no

sources for anything. If not for this, the book would have received five stars.

MOB RECIPES TO DIE FOR

Mob Recipes to Die For. Meals and Mobsters in Photos Paperback – December 20, 2011

READERS REVIEWS FROM AMAZON BOOKS

This is a funny book, okay a little bloody in places but believe it or not, the recipes are actually pretty good and there are several good stories about mobsters and meals. The mob stories are mixted with authentic Italian recipes and other Outfit anecdotes and all of it makes for fun reading and actually some pretty good cooking.(Including the meat sauce recipe from the prison scene in "Gooodfellas") Most of the recipes are very simple fare, quick to make and include classic dishes like Shrimp Scampi, a simple Tomato Sauce, Veal Piccata, Asparagus with Prosciutto, Baked Stuffed Clams, Veal Chops Milanese, Caponata and Lobster. The book has about 50 something photos of dead mobsters followed by a recipe.The bloody scenes aside, this book would make compliment most cooking libraries and will works especially well for the novice cook.

There

is no shortage of corpses in this book. Its page after page of dead hoodlums

from the underworld with a passage on how they got that way and by whom. Gory

but I must say, fascinating as the violence of the underworld so often is. The

book is a guilty pleasure.

The

Salerno Report. The Mafia and the Murder of President John F. Kennedy: The

report by Mafia expert Ralph Salerno Consultant

to the Select Committee on Assassinations

READERS REVIEWS FROM AMAZON BOOKS

A

must read for anyone studying the Kennedy assassination. Among the many

conspiracy theories is the possible involvement of Mafia. As we all know there

are no definite conclusions, and history may never resolve the issue, but this

report is engaging and captive reading..

The

Salerno Report is far more accurate than the Warren Report

Evidence

mounted in a certain direction. The truth is still discoverable, and this

ghastly event in our history deserves still more examination. This book

contributes to the eventual revelation of what really happened.

Rosenthal murder case

READERS REVIEWS FROM AMAZON BOOKS

"The old Metropole. The old Metropole," brooded Mr. Wolfshiem gloomily. "Filled with faces dead and gone. Filled with friends gone now forever. I can't forget so long as I live the night they shot Rosy Rosenthal there. It was six of us at the table, and Rosy had eat and drunk a lot all evening. When it was almost morning the waiter came up to him with a funny look and says somebody wants to speak to him

outside. 'all right,' says Rosy, and begins to get up, and I pulled him down in his chair. "'Let the bastards in here if they want you, Rosy, but don't you, so help me, move outside this room.' "It was four o'clock in the morning then, and if we'd of raised the blinds we'd of seen daylight."

"Did he go?" I asked innocently.

'Sure he went." Mr. Wolfshiem's nose flashed at me indignantly. "He turned around in the door and says: 'Don't let that waiter take away my coffee!' Then he went out on the sidewalk, and they shot him three times in his full belly and drove away."

"Four of them were electrocuted,"

I said, remembering. "Five, with Becker"

The Great Gatsby

The Becker-Rosenthal trial was a 1912 trial for the murder of Herman Rosenthal by Charles Becker and members of the Lenox Avenue Gang. The trial ran from October 7, 1912 to October 30, 1912 and restarted on May 2, 1914 to May 22, 1914. Other procedural events took place in 1915.

In July 1912, Lieutenant Charles Becker was named in the New York World as one of three senior police officials involved in the case of Herman Rosenthal, a small time bookmaker who had complained to the press that his illegal casinos had been badly damaged by the greed of Becker and his associates. On July 16, two days after the story appeared, Rosenthal walked out of the Hotel Metropole at 147 West 43rd Street, just off Times Square. He was gunned down by a crew of Jewish gangsters from the Lower East Side, Manhattan. In the aftermath, Manhattan District Attorney Charles S. Whitman, who had made an appointment with Rosenthal before his death, made no secret of his belief that the gangsters had committed the murder at Charles Becker's behest.

At first, John J. Reisler, also known as "John the barber," told the police that he'd seen "Bridgey" Webber running away from the crime scene directly following the killing. He recanted under duress from gangsters the next week, and was charged with perjury.

The investigation was covered on the front page of the New York Times for months. It was so complex that the NYPD recalled thirty retired detectives to help investigate; they were said "to know most of the gangsters."

One of these old-timers, Detective Upton, formerly of the NYPD "Italian Squad," was instrumental in the July 25, 1912, arrest of "Dago" Frank Cirofici, one of the suspected killers. He and his companion, Regina Gorden (formerly known as "Rose Harris"), were "so stupefied by opium that they offered no objection to their arrests," according to the New York Times.

Joe Petrosino

READERS REVIEWS FROM AMAZON BOOKS

Any book about Joe Petrosino can't be all bad. Far too little attention is paid to Petrosino these days. The foolish Public remembers names of scumbags like Capone, Gotti, Valachi, Tony Soprano, etc. Far too few people remember New York Cop Joe Petrosino. In a time when Italians were segregated, harassed by Cops and treated as second class citizens, Petrosino arose as the first Italian anti-gangster Cop. Then, as now, gangsters claimed they were the victims of prejudice, discrimination and profiling. Petrosino rose above his times to become a Pioneer in anti-Mafia police work. Tough as nails, un-corruptible, and utterly fearless, Petrosino was assassinated by the Mafia in their usual cowardly style.

This book is a welcome bit of scholarship on the great Petrosino. Tuohy's book does contain an, apparent, misprint. There is a lone word, without authority, regarding Petrosino being "corrupt," perhaps a reference to his tough police tactics. Corruption, however, implies a personal power or profit motive. Tuohy provides no evidence or argument of any such motive or activity on Petrosino's part. On the contrary, the only evidence is that Petrosino was a good, honest Cop. Petrosino is a role model for young and old alike, oppressed immigrants, and even whining minority gangsters and their sympathizers, such as Sharpton, Obama, Jackson, and Holder.

I have several books from The Mob Files Series and I have really enjoyed reading them. The Joe Petrosino story is definitely one worth reading. He had an interesting life working against the mafia. I enjoyed seeing the pictures in the book and they helped bring the story to life.

AND HERE'S SOME ANIMALS FOR YOU...................